Manufacturer's Specifications

Frequency Response: 20 Hz to 20 kHz, ±0.3 dB.

Dynamic Range: Greater than 90 dB.

S/N Ratio: Greater than 90 dB (20 Hz to 20 kHz).

Channel Separation: 86 dB (20 Hz to 20 kHz); 90 dB at 1 kHz.

Total Harmonic Distortion Plus Noise: Less than 0.005%.

Wow and Flutter: Unmeasurable, quartz crystal precision.

Line Output Level: 2 V rms.

Power Consumption: 20 watts.

Dimensions: 12.6 in. (32 cm) W x 2.87 in. (7.3 cm) H x 10.51 in. (26.7 cm) D.

Weight: 11 lbs. (5 kg).

Price: $800.00.

Company Address: c/o NAP Consumer Electronics Corp., P.O. Box 6950, Knoxville, Tenn.

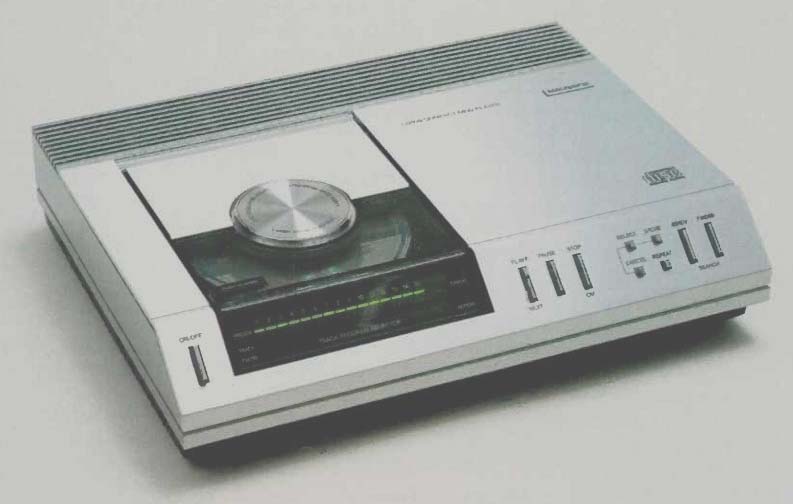

Billed as the smallest Compact Disc player in the world, this attractively styled unit is also the lowest priced of three models to be offered by Magnavox. Magnavox, as you probably know, is a wholly owned subsidiary of North American Philips. And North American Philips, in turn, is owned by Philips of Holland, to whom must go the primary credit for the development of the CD format, which has already be come an international standard. Although credit for the disc and player is generally shared by Philips and Sony, the truth is that Sony's primary contribution was in the area of the error-correction systems that were ultimately adopted. It was Philips which began work on the digital disc idea way back in 1969 and 10 years later showed the first working system to the European press.

The unit I tested, in fact, bore the model number CD-100, suggesting that it was actually a sample of the Philips model being sold in Europe, with its power supply modified for use in the U.S. We are told, however, that the configuration and all of the features of this model are otherwise identical to the Magnavox FD1000SL, which will be the American designation for this truly “compact” compact disc player.

Magnavox maintains there are subtle differences in the quality of sound reproduction between various manufacturers' CD players, and they attribute this to technical differences in the way the players reproduce sound. The main difference is in the signal-conversion process from digital back to analog. All of the units I have tested to date (with the exception of the Phase Linear Model 9500) use straight 16-bit D/A converters with steep analog filters. Some listeners maintain that the use of a sharp cutoff filter results in considerable phase shift in the 20-kHz region; they perceive this as detrimental to proper stereo imaging and reproduction of transients.

The Magnavox player incorporates three techniques that are said to provide the effectiveness of a pure 16-b t system, but which require a simpler digital-to-analog converter with simpler filters. First, "oversampling" is used. This has the effect of reducing noise in the audio band by an additional 6 dB. The technique involves sampling the digital signal at four times the normal rate, thereby distributing the noise over a broader spectrum. Secondly, digital filtering is used to remove ultrasonic components while maintaining phase linearity up to 20 kHz. Finally, noise shaping is used to reduce noise in the audio band by an additional 7 dB while increasing noise outside the audio band. The unwanted high-frequency noise is then eliminated with simple analog filters.

Unlike any of the CD players I have previously tested, the FD1000SL is a top-loading unit. Depressing a designated area on the see-through hinged door on the player's top surface causes that door to pop open. The Compact Disc is simply placed on the exposed center spindle, and the door is closed manually. All remaining controls and displays are on the gently sloping front surface. A power on-off pushbutton is at the extreme left. A display area labeled "Track Program Selector" occupies the same left-to-right length of the sloped surface as does the disc-loading door on the top surface, making for an extremely pleasing and integrated look. When power is first applied, a bank of green LEDs, numbered from 1 to 15, illuminates. If the "Play" button to the right of the display area is then depressed, disc playing will commence from the first track and an additional row of LEDs below the "program" LED bank will display the current track being played. "Pause" and "Stop" buttons are located alongside the "Play" touch button. An additional LED lights up in the display area when the "Pause" button is activated.

Touching the "Pause" button a second time causes ,play to resume and extinguishes the "Pause" LED.

----- Booklet, demo disc and cleaning cloth packed with the player.

In addition to this straightforward approach to the playing of Compact Discs, the FD1000SL offers several other options, including programming of desired selections on a disc in any given order. Four tiny touch buttons further to the right are identified as "Select," "Store," "Cancel" and "Re peat." Pressing the "Repeat" button causes the entire disc to be played over and over again until the button is de pressed a second time or until "Stop" is depressed. While in the repeat mode, another LED in the display area lights up to indicate that fact. The three remaining buttons in this area provide the user with two different methods of programming. The "Select" button, when depressed, moves the "track" LED in the display, one track at a time, to any desired track from 1 to 15. When the desired track you want to hear first is indicated, touching the "Store" button places that track number in "memory." By repeating this sequence of operations, a method referred to in the owner's manual as "Add-In Programming," you can program in as many tracks as you like, in any order you choose.

An alternate method of programming, called "Take-Out Programming," is used if you want to hear most, but not all, of the selections contained on a particular disc. In that case, the "Select" button is used to bring the moving LED to the track that you don't want to near, and the "Cancel" button is then touched. Upon completing this routine, the appropriate LED in the upper bank of "Track Program Selector" LEDs is extinguished, indicating that that particular track will be skipped when it is reached. The procedure is repeated until all undesired tracks have been selected. If the "Play" button is then depressed, disc play will commence and will proceed in order, from track to track, skipping only those tracks that you have "cancelled."

The remaining two touch buttons on the sloped front panel are "Search" buttons that are used to advance the laser rapidly in either forward or reverse direction. Although there is no sound heard when using the "Search" buttons, the current track being scanned at any instant by the laser pickup is indicated by an appropriate LED in the display. If you should inadvertently hold down a forward or reverse search button so that the laser reaches the end (or the beginning) of the disc, an "Error" light will come on.

In this Magnavox player, the emphasis is clearly on purity of sound reproduction and ease of programmability. Certain features I have encountered on other CD players have been omitted, however. For example, no time indications are provided either as to time remaining on a disc or time into a given track being played. No doubt some of Magnavox's more expensive models to be offered in the future will incorporate additional features.

Measurements

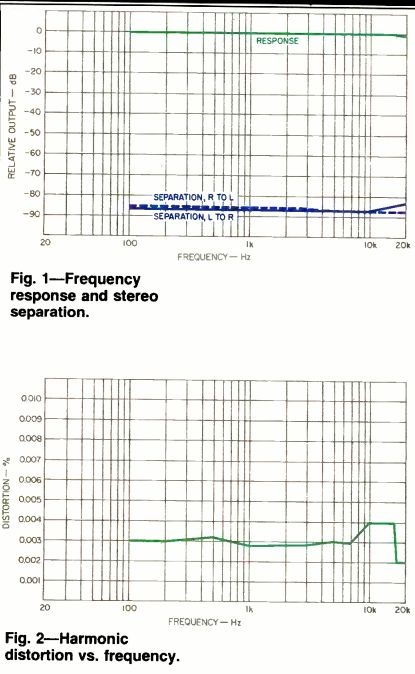

A point-by-point plot of frequency response (upper curve) and channel separation capability for the Magnavox FD1000SL is shown in Fig. 1. Maximum departure from flat response in the range covered by the test disc (100 Hz to 20 kHz) was never greater than 0.2 dB, and even that deviation was noted only for the 18- and 20-kHz test signals. Separation, represented by the lower curves in Fig. 1, ranged from 83 to 87 dB for left-to-right channel crosstalk and from 86 to 87 dB for right-to-left channel crosstalk.

Harmonic distortion versus frequency at 0 dB is shown in Fig. 2; readings ranged from 0.002% to 0.004%. At the-10 dB level of the 1-kHz test tone on the disc, THD rose to a still completely insignificant 0.0085%. At -20 dB level, THD increased somewhat further to 0.023%.

Decreasing-amplitude 1-kHz test tones were also used to check linearity of the playback system. Absolutely perfect linearity was noted from 0 dB level all the way down to -60 dB. At -80 dB, linearity seemed to be off by 1.0 dB, and at -90 dB I read an output of-88 dB, which may well have been residual noise in my test setup rather than actual departure from true signal linearity.

Signal-to-noise ratio measured 92.5 dB, unweighted, increasing to 99.5 dB when an A-weighting filter was inserted in series with the measuring instrument. At 0 dB recording level, SMPTE IM measured 0.0056%, increasing to 0.013% at -10 dB level. Measurements for CCIF (twin tone) IM were 0.0010% and 0.0025% at 0 and -10 dB record levels, respectively. De-emphasis was accurate to within 0.1 dB at the three test frequencies of 1, 5, and 10 kHz included in the test disc.

Fig. 1-Frequency response and stereo separation.

Fig. 2-Harmonic distortion vs. frequency.

Use and Listening Tests

Happily, my collection of CD records is growing by leaps and bounds. I now own more than a dozen of these amazing little discs, and I am pleased to report they are getting better and better, musically speaking. Someone out there must be listening to those of us who have suggested that new mixing techniques and approaches (or are they really "old techniques" after all?) are going to be needed if the Compact Disc's potential is to be realized. Two recent acquisitions are from RealTime Records (Miller & Kreisel Sound Corp.).

One is from their "Digital Masterpiece Series," Zoltan Rozs nyai conducting The Philharmonica Hungarica in selections by Brahms, Berloz, Chabrier, Rossini, Bizet, Dvorak, Dukas and Liszt. The other, Real Hot Jazz, features jazz-band mu sic by the likes of Don Menza, Jack Sheldon, John Dentz and Freddie Hubbard and their assorted musical aggregations. If you want to know how totally thrilling digital disc reproduction can be, drop either of these (depending upon your musical taste) into any CD player and you'll be an immediate convert.

Could I hear a "difference" between the sound produced by the Magnavox unit and my own reference CD player? Frankly, no! The new discs sounded absolutely superb on both. This is not to say that you won't be able to detect some subtle differences if you listen long enough. All I'm saying is the CD experience is so overwhelming compared to any analog listening I've done over the years, that straining to pick out hitherto undetectable flaws seems a pointless exercise to me. I prefer to enjoy the music-as I've never enjoyed it before-and to thank the people at Philips (and, yes, those at Sony, too) for bringing this miracle to us during our lifetimes.

This much I will say: The earliest CDs in my collection, and those that were produced from less-than-excellent analog master tapes, point up their failings on any type of CD player, while the most recent Compact Discs sound good on both the Magnavox and my reference player. In that connection, the Philips unit I received for testing was magnificently packaged. Included with it was a Philips Compact Disc containing 14 cuts, eight of them pop music, the rest in the classical domain. This disc, too, offered a superb example of how CDs should be engineered. Magnavox would be wise to offer their version of the player packaged just as it was by Philips, including this magnificent sampler. As for the Magnavox CD player, its small size, excellent design in terms of ergonomic factors and its relatively low price make it a sure winner.

-Leonard Feldman

(Adapted from: Audio magazine, Jun. 1983)

Also see:

Magnavox CDB650 CD player (Equip. Profile, Mar. 1987)

Mission PCM-7000 Compact Disc Player (Aug. 1987)

Onkyo DX-G10 Compact Disc Player (Mar. 1989)

= = = =