By Gary Stock

Rags-to-riches tales of hardworking entrepreneurs are fairly commonplace in the United States but not so in Europe, where class distinctions and remnants of the guild system have made upward mobility a relatively uncommon achievement. Willi Studer, founder of the Swiss-based Studer Revox group, surmounted all of these factors and built a company whose name is known worldwide for performance based on extremely high standards of precision and careful design. At the age of 68, Studer stills runs the activities of the company in both its professional and consumer veins, and he is active in design.

Dr. Studer has been in the electronics manufacturing business for many years.

He left an apprenticeship program after his graduation from high school in order to market his own radio receiver at the age of 19. Two years later, he and a partner formed Sondyna--a firm still in existence--to manufacture his receivers in large quantity. From there, he pressed on into test equipment, founding two firms -- one which produced measurement instruments and his first audio products, and another which built electrochemical test equipment, including a then-exotic oscilloscope.

Studer's first involvement with tape recorders -- the product which has come to be most closely associated with the Revox and Studer names -- came in 1949, when the European importer of the U.S.-built Brush tape recorder asked Studer to modify a group of these recorders for European voltages and line frequencies. After engineering all of the complex elements required for the con version, Studer bought 500 of the machines to sell himself and simultaneously commenced development of a recorder of his own design. Marketed in 1950 under the Dynavox name, the first Studer-developed recorders were rapidly accepted among broadcasting and professional users, and the company's long tradition of simultaneous involvement in professional and amateur recording applications began.

Throughout the '50s, Studer Revox built the compact, extremely rugged open-reel machines that were de rigueur among the location recordists of the day, including early examples of three-motor-transport-equipped and direct-driven machines (both introduced in 1954).

Studer Revox products from the '60s and '70s are readily familiar to American audiophiles. The A77 portable open -reel recorder was among the most successful reel-to-reel designs ever marketed in terms of sales volume and was remarkably long-lived for a consumer electronic product as well (12 years without major changes; now succeeded with the B77). A series of amplifiers, preamplifiers, and tuners based on the visual styling of the A77 have met with only moderate success in the U.S., perhaps due to their cosmetics or their comparatively modest power out put ratings, but they remain very well respected throughout Europe and Asia.

The company is now a major manufacturer of loudspeakers, tangential-tracking turntables, a full spectrum of professional recorders and ancillary equipment.

Dr. Studer himself possesses enormous personal reserve; his voice rarely rises above a murmur. In contrast to an extraordinary personal containment, however, are Studer's candidly expressed judgments of the future of high fidelity, his competitors, and the road to The Digital Revolution. Here, he goes far beyond the degree of openness revealed by most corporate executives, as can be seen in his conversation with Features Editor Gary Stock.

Audio: Studer Revox has made its position of welcoming the Digital Revolution' while continuing to work with analog technology admirably clear in recent months, but the specific formats and technological approaches that your company will support haven't yet been discussed publicly. Where will Revox go, for instance, with respect to a digital audio disc format, and will you become involved in the manufacture of a digital audio -disc player?

--------The Revox A77 was popular for more than a dozen years.

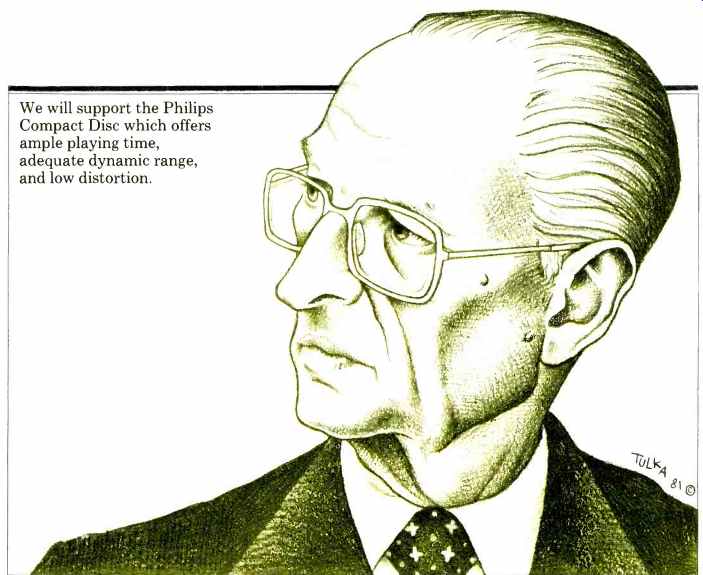

Studer: We will support the Philips Optical Compact Disc format which as you know uses a small, 4 3/4-inch disc read by a laser element. The reasons for our choice are straightforward. The Philips system offers ample playing time, adequate dynamic range and low distortion, all in a compact form. It does not make the error of being too complex in its digital encoding or in its physical mechanism, just for the sake of specifications.

We intend to manufacture a disc player as soon as it is appropriate to do so, and we will, in fact, shortly be acquiring a Compact Disc license.

Audio: What about efforts in related fields? Will Studer Revox also become involved with the videodisc, or perhaps videocassette?

Studer: Our intention is to remain in the audio field. But there is no question that the digital disc will be in our development program.

Audio: What about the idea of a consumer digital tape recorder?

Studer: We have done considerable thinking on that question. One approach that could be realized using current -day technology would be a digital cassette recorder using either the Elcaset or the Unisette. [These are both large two-reel-cassettes developed as high-quality alternatives to the traditional Philips cassette. -- Ed.] Such a device, with a sampling rate somewhere between 34 and 44 kHz, would have the capability of 45 minutes of stereo playback. With the proper analog-to-digital and digital-to-analog (A-D and D-A) converters, there need be no audible phase shift to 18 kHz, and beyond that, a man of my age cannot hear [laughter].

Audio: But would this approach be the ideal one, or is a clean sheet of paper the best starting point for a consumer digital tape machine?

Studer: Neither the Unisette nor the Elcaset is an ideal device. We would like to propose a new type of cassette pack age, specifically designed for the purpose.

Audio: What would a cassette designed for digital look like?

Studer: Somewhat different from either Elcaset or Unisette. For one thing, the spools on the Elcaset are held in place by the player when it is loaded to prevent friction that could cause wow and flutter and to provide a carefully controlled movement of tape. Such a technique is not really so important when the tape is digitally encoded because one can do a lot of electronic correction, making a PCM recording much less affected by mechanical wow and flutter. With a new cassette format, one could simplify the mechanical elements and reduce the cost considerably. However, in any new cassette designed for PCM, one would have to pull the tape out of the cassette in order to play it and guide it accurately across the heads. This is because a very low tape speed would be required on this type of cassette, due to the need for distributing the musical information on several tracks to facilitate the correction of errors.

Audio: Then a great deal of redundancy would be built into the format. [Redundancy is the deliberate repetition of information done in order to prevent a momentary signal loss from eliminating parts of the final signal. -- Ed.]

Studer: Yes, in order to distribute the information. The density of information on such a digital cassette would be so high that one is dependent on a very good out-of-shell tape guidance system where the tape does not skew.

Audio: How large would such a cassette be, and what tape width would it use?

Studer: It would probably use 1/4 -inch tape, and be about the size of a Unisette or Elcaset [which are in turn approximately the size of a Beta-format video cassette -- Ed.].

Audio: How much would one of these digital recorders cost, and how soon could it be available, either from Studer Revox or another source?

Studer: Machines of this type could be built within four to six years, and the price would probably be approximately $3,500 U.S. (1980). Technology is changing very rapidly, though, and in four to six years we will have very highly integrated circuits, and these chips will bring the price down considerably in the first couple of years after the product is introduced.

Audio: What might the price be after a full reduction of all electronic elements to integrated-circuit form?

Studer: A good digital tape recorder won't ever be as cheap as a good cur rent -day cassette recorder because the heads in a digital unit will require multiple, extremely narrow gaps. These heads will always be considerably more expensive than a normal analog tape head. A digital tape machine could eventually cost as little as $1,500 U.S. once the chips become available, how ever.

Audio: Do you feel that present-day digital studio recorders have substantive sonic deficiencies? Is there a characteristic "digital coloration" that they impart to music?

Studer: There is some coloration. De spite what is said to the contrary, copies made over four generations on a digital machine sound far worse than first-generation tapes or tapes made on a good analog machine. It all comes back to the fact that present-day A-D and D-A converters are the source of the problem.

There are extremely good converters available, but they are also extremely ex pensive. With the right converters and the right anti-aliasing filters, there need not be any distinctive "digital coloration." Remember that new technology is never perfect at the time of its first commercial introduction. The automobile is over a century old, yet still very imperfect.

Audio: A question about the business side of the audio industry, Doctor. Given the present rates of currency exchange, virtually all Western European goods -- be they German automobiles, Swiss watches, or French suits -- are rather expensive by American standards, Japanese-made products, including their audio products, are by contrast moderately priced. How do you see this disparity affecting the future of Studer Revox? Do you think that European products of high quality can remain competitive with Far Eastern goods?

Studer: There is no way that we in Western Europe can compete directly with Japanese mass-produced merchandise.

In 1979, our basic labor wage in Germany was 23 Deutschmarks per hour, while in Japan, the basic wage was equivalent to 16 Deutschmarks. The Japanese work a week that is 15 hours longer, on the average, and also work more in tensely than Europeans or North Americans. The only salvation for a European company is to offer superior technology, greater innovation, and a better -quality product. That is the only way for us to survive and prosper.

Audio: If large Japanese firms continue their large-scale research and development efforts, however, can European companies continue to hold an edge in innovation? Or is it likely that Japanese products will become as technically advanced while the production costs of the Far East remain moderate?

Studer: I can only speak for my company, but I believe we will retain our edge over Far Eastern competition. Our company is not a typical commercial firm in that there is a lot of idealism both on my part and on the part of the employees.

That should make all the difference. We do not intend ever to lag behind in technology. A very substantial part of our profit is invested in new technology, new machinery, and so on. We believe strongly in a commitment to remaining first in our field.

Audio: As you are a major innovator in the field of high fidelity, I'm interested in your perspective on upcoming changes in home high-fidelity systems. Do you believe that we will see a return to multi channel sound in the home -- that is, more than two channels -- as a means of reproducing concert -hall ambience or other special sonic effects?

Studer: No. I don't believe that the quality of reproduction we have today will be greatly improved by the addition of more channels of information.

Audio: What do you feel will be the next big step forward in home high fidelity?

Studer: There is no question in my mind that the introduction of the PCM disc will mark the next milestone in audio development. Two of the most serious problems we have in home music reproduction -- dynamic range and distortion -- will both be greatly reduced in magnitude by the digital disc.

Audio: Beyond the digital disc, what might be the step that follows?

Studer: I see certain possibilities. One is to substantially increase the storage density of the medium, which will in turn improve its resolution and playing time.

Whether this will have any direct sonic benefit is another question. All things considered, though, I think I am content for the moment to work on achieving the full benefits of digital technology and to wait a bit for the step that follows.

==============

STUDER'S LATEST

After years of speculation about the intentions of Studer Revox in the cassette field, the company will intro duce its first cassette machine some time this spring. The B710, as it is designated, is pure Revox: Unorthodox in approach, visually distinctive, built like a battle cruiser, and concomitantly pricey. Some recording-studio engineers and serious audiophiles are already calling it the "reference standard cassette deck," based on the Revox reputation and a brief U.S. showing last autumn.

The B710's transport consists of a total of four motors mounted on massive multiple castings; two direct-drive spooling motors and a Hall-effect capstan motor for each of the two capstans. As is common in European cassette machines, the cassette snaps into place on the front panel, rather than being held in an enclosed well. The head block assembly is hinged and swings up like a trap door to engage the tape. The entire trans port is controlled by a microprocessor that also runs the digital display and clock functions, the deck's various memory functions, and a timer circuit capable of turning on both the deck and an ancillary component at a predetermined time.

Interestingly, despite the presence of a microprocessor, Revox has chosen not to incorporate an automatic bias/equalization optimization circuit of the type now popular on top-line Far Eastern cassette decks, and has also located the B710's bias fine-adjustment potentiometer internally, rather than on the front panel. Dr. Studer comments that such adjustments can only be made with precision by technicians using the appropriate test gear. The machine does incorporate automatic switching of EQ based on the coding slots found in many cassette shells, as well as manual tape selector switches. An other interesting point concerns the Dolby HX switch in the lower left portion of the prototype's faceplate. Revox engineers decided in the latter stages of development to remove the feature (production versions will obviously not have the switch). Dr. Studer noted that "the disadvantages of Dolby HX, especially with respect to modulation noise, proved in the end to outweigh the advantages." Metering on the B710 is done by two LED bar displays, calibrated in 1-dB increments from - 10 to +6 dB and in 2 -dB increments over most of the remainder of their range. The heads are Revox-built Sendust/ferrite units. As is characteristic of Studer Revox equipment for both home and professional use, the electrical elements of the B710 are individual printed circuit modules that lock into a master board.

Oh yes, the price. If you have to ask, you may not be able to afford it.

Revox estimates the ticket at about $1,800. After all, Swiss precision never comes cheap. -G.S.

The Revox B710 will be the firm's first cassette deck.

==============

==============

A DIGITAL MANIFESTO

The worldwide transition from analog to digital that we'll witness over the next decade will be an expensive, involved, and risky stage for manufacturers. Those firms which develop or back the right formats and technical approaches will reap huge rewards, while the losing firms will in some cases lose big. Many companies in the audio industry, therefore, are jockeying for position, remaining uncommitted on the issues of standards and formats, and sizing up the competition.

All of which makes the Studer Revox position on the digital transitional phase a refreshingly candid one. In addition to taking clear, early stands on its choices for both professional and consumer digital formats, Studer Revox has also promulgated a sort of Digital Manifesto that discusses the technical and political sides of the digital transition in very candid terms.

Released to both the press and the professional recording community late last year, the 26 -page brief discusses Studer Revox objectives and thoughts on achieving a smooth transition with a precision of thinking that matches what goes into its motors, circuit boards, and tape heads.

The document speaks for itself best:

"Audio PCM is on its way. As we all know, the first prototypes are operating, and the first multichannel recorders will soon be available on the market . . . . Will Studer go PCM? Yes, Studer will ... .

"At the same time, we think that analog equipment still has a long way to go. Too much has been invested in analog products to discard them hastily. New, improved, easier -to -use analog products will appear along with matching PCM components. If they are correctly designed, they can coexist peacefully for a while... .

"Introducing PCM the right way, at the right time, is a vitally important task for both users and manufacturers. To help you decide how, and when, and how fast audio PCM should be introduced, we would like to give you a few facts about the emerging technology ...

"There is little doubt that audio PCM studios will have to accommodate at least two sampling rates, one for studio recordings and the other for consumer recordings. Translating a digital signal from one sampling rate to another is basically possible, al though it may involve a great amount of circuitry .... Sampling rate con version is made very much easier if the two sampling rates are in simple ratio, like 8 to 7. The cost of conversion increases very rapidly if unfavorable sampling rate ratios are chosen or if they become necessary be cause of conflicting standards ...

"There should be standards for audio PCM discs, pseudo-video PCM on VTRs (both consumer and professional), and for stationary head studio machines. The different standards should be harmonized, and make signal conversion and transfer from one product to the other relatively easy. In the long run, bad standards cost a lot of money and effort .... We need an interface definition for digital audio, with an audio PCM signal format, and control bits for simple interconnection and remote control. This means connectors, plugs, signal levels, timing, and lots of details.

"How should standards emerge? Perhaps by consensus, though we doubt it. If the process of standardization by conferences is too slow, the proposals of a major manufacturer of audio PCM should be adopted."

==============

( Audio magazine, Apr. 1981)

Also see:

The Audio Interview: Rudy Bozak (May. 1982)

Interview with Les Paul (Dec. 1978)

DvR's Latest: The Analog Bass Computer (Feb. 1981)

= = = =