Behind The Scenes (Apr. 1990)

BERT WHYTE

LORE OF NOSES

The Sunday, December 31, 1989 edition of The New York Times featured an article in its "Arts and Leisure" section that was intriguing and amusing. In his facetious but somewhat frightening glimpse into the future of entertainment media, John Rockwell told about the English National Opera's new London production of Prokofiev's satirical opera, Love for Three Oranges. It certainly is a work that is not presented very often, but what made this production unique was that director Robert Jones had provided each audience member with a card containing a number of those scratch and-sniff panels that have been appearing in magazine ads for some years now. Each panel was cued to a key scene. As you might expect, scratching one panel produced the smell of oranges; others emitted the smells of rotting meat, disinfectant, and "a cross between bad eggs and body odor," which emulated the giant Farfarelló s bad breath. An exotic perfume was used for the finale. Thus, this was a multi-sensory experience for the audience, which saw, heard, and smelled its way through the opera.

Tongue in cheek, reporter Rockwell suggested that future productions could include the scent of roses for Der Rosenkavalier, gingerbread for Hansel and Gretel, and briny smells for Wagner's Flying Dutchman.

By sheer chance, a few days after reading this article, I received Virgin Classics' two-CD set of the first recording of the original French version of Prokofiev's Love for Three Oranges. I hasten to add that it was not accompanied by scratch-and-sniff panels, but how far off can the day be when some company opts for this gimmick, along with visual elements through CD graphics? The CD Video operas would be a likely medium, a thought that will send chills through many! The unusual production of Love for Three Oranges proves once again that there is nothing new under the sun.

Way back in 1959, there was such a thing as SmelloVision. When Mike Todd, Jr. wanted to make a blockbuster production like his flamboyant father's Around the World in 80 Days, someone sold him on the idea of incorporating a wide-screen, Cinemascope type format, six channels of surround sound, and the production of odors cued to the action on the screen. The film was entitled Scent of Mystery and starred Peter Lorre. I recorded the six channel stereo on 35-mm magnetic film in the famous Cinecitta film studios in Rome. What an experience! The score was composed by Mario Nascimbene, well known for music for "spaghetti westerns." The conductor of the large symphony orchestra that was used, a protege of Toscanini, kept insisting that his involvement with the recording be kept secret because he considered it "demeaning"! The action was set in Spain, and when Peter Lorre walked by one of those "beehive" ovens seen in the Spanish countryside, the SmelloVision process produced the odor of freshly baked bread. In all, over 40 smells were used.

Scent of Mystery opened at the Rialto Theater in New York City. On each seat back, a rectangular black box was mounted. As the frames ran through the film gate, optical cues triggered from the black box whatever smells were appropriate to the scene.

Even though none of the odors was really offensive and the odors' integration with the scenes was quite clever, Scent of Mystery was a resounding flop.

For many years, the movie industry has attempted to create more audio/ visual impact and a heightened sense of realism in its productions. The appearance and threat of TV, which for a while shuttered many movie houses, made advances in sound and projection even more desirable and urgent.

In the early 1950s, 3-D films offered novelty, but the necessity of wearing glasses with red and blue lenses in order to view them, and their very low screen brightness, were negative factors. Writer Arch Oboler produced a famous 3-D film, Bwana Devil, starring a young Robert Stack. When I was with Magnecord in Chicago, Oboler asked me to record a binaural soundtrack for Bwana Devil. However, the logistics of the undertaking were just too formidable in those days, so the idea was abandoned.

I have previously related the story of wide-screen Cinemascope and its original stereophonic sound. There is not much doubt that the best of the wide-screen processes incorporating stereo sound was Cinerama. The idea was developed from the simulated scenery used in the Link Trainer to instruct aircraft pilots. The Cinerama screen curved around 168°, pretty close to the limits of human peripheral vision. Three special cameras were used to photograph scenes. The processed film was shown through three synchronized projectors, and you could faintly see areas where the edges of the images overlapped. Six channels of stereophonic sound were used in a non-surround configuration.

Several well-known personalities were connected with Cinerama, including Lowell Thomas and my friend Sherman Fairchild.

Sherman had an engineer, Wentworth Fling, who modified Fairchild tape recorders (originally used by Bob Fine for his Mercury Olympian recordings) for the Cinerama stereo soundtrack. The theaters themselves had to be modified to show Cinerama, and they were in various places in the U.S. and overseas. Because of the films' international distribution, their soundtracks were remixed for various foreign languages. This was done just 20 minutes from my home in a unique facility on Long Island, an area once known as the Gold Coast because of the huge estates of the very rich. By the early '50s, when Cinerama was developed, this facility, the Woodward estate, had become a white elephant, virtually unused. However, it had indoor tennis courts so huge that a complete Cinerama screen and theater were installed in the building.

Sherman Fairchild allowed me free run of the place, and I was often privileged to be the only occupant of the theater, where I saw and heard This Is Cinerama in German, French, Italian, and Spanish. If you were lucky enough to be seated at the center of the Cinerama screen, at a distance at which your peripheral vision was within the 168° screen wraparound, the sense of three-dimensional immersion in the film was truly fantastic! In the Cinerama production of Windjammer is a scene of a square-rigged ship under full sail. As the ship swings on a starboard tack, the long-pointed bowsprit sweeps across your vision and can make you a bit dizzy. In How the West Was Won, an explosion on a riverbank sends wooden barrels hurtling out of the screen at you! As for this film's six-channel stereophonic sound, a chorus singing, "Oh, Shenandoah" at the beginning was quite breathtaking. Alas, production costs and other factors caused the demise of Cinerama, but it was one hell of an audio/visual thrill.

This brings us full circle, to the modern technology that gives us the Dolby Stereo movie theater experience and its re-creation in the home via prerecorded videotapes and laser videodiscs. The proliferation of Dolby Surround processors and integrated audio/video home theater systems has become something of a phenomenon.

During the Winter CES in Las Vegas, speakers at various seminars made much of the home theater system as an increasingly important segment of the consumer electronics industry.

Keynote speaker Bernard F. Brennan, chairman and president of Montgomery Ward, when discussing the home theater and surround sound market, stated, "A major factor that will affect the '90s is the graying of the consumer base. This change in demographics to an older population is developing the concept of 'cocooning'-that is, spending a great deal of time in one's home. This trend offers us the opportunity to fulfill the home theater needs of this growing consumer group.", I am a little amused by the reference to "cocooning." Eleven years ago, at the 1979 AES Convention in Los Angeles, a special UCLA Extension conference was hosted by Martin Polon (who now writes witty and informative columns for Studio Sound). The conference was entitled "The Revolution in Home Entertainment: New Technology's Impact on the Arts." The panel of experts included John Eargle; the late Richard Heyser; John Dykstra, the special-effects engineer for Star Wars, and yours truly. Some very high-flying ideas were proposed, and some have become reality in the past few years. A May 18, 1979 article in The Los Angeles Times reported on the far-ranging concepts at the conference. The writer quoted me directly on what I call my "enclave theory"--the idea of people becoming more and more involved in a wholly self-contained, self-sufficient home, a sort of intellectual bastion with all the hardware and software necessary for audio and video entertainment and all the environmental concerns under one centralized control. It was at this conference that I first publicly discussed the idea of the computer-accessible central audio/video library I mentioned in last issue's column.

Today, various aspects of the home electronics enclave, including high definition TV, are widely discussed.

But in all this talk, HDTV is bandied about as if its introduction is imminent.

Unfortunately, this is not the case; despite all the activity, no standards have been formulated, no system chosen. It will be quite some time before anyone in the U.S. will be able to walk into a dealer to buy a 1,125-line TV set. For now, it's as much a reality as attempts to expand the theater experience beyond sound and vision.

(adapted from Audio magazine, Apr. 1990; Bert Whyte)

===========

ADs:

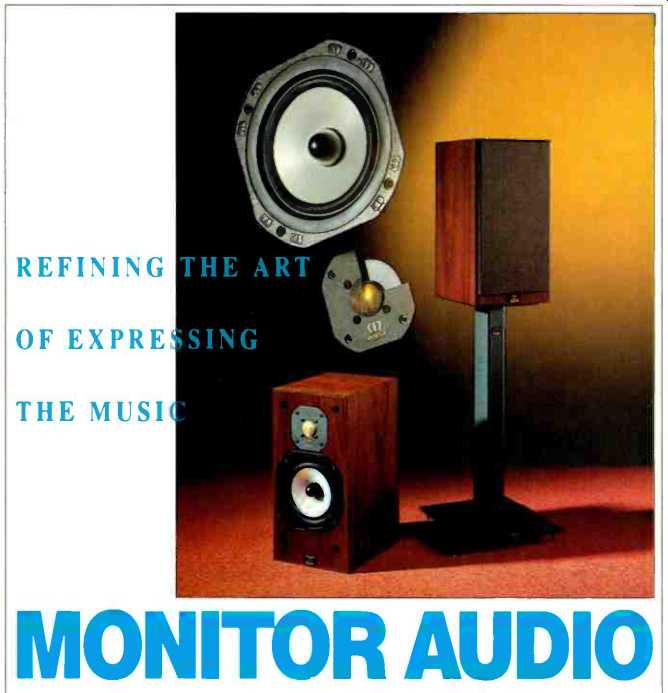

MONITOR AUDIO

REFINING THE ART OF EXPRESSING THE MUSIC

MADE IN ENGLAND

Making music is an art; making loudspeakers is a science. Nowhere will you find leading-edge technology put to finer effect than with Monitor Audio.

Monitor Audio's gold-dome tweeters and ceramic coated metal cone woofers work as one, producing staggering detail and dynamics within a coherent sound stage.

Beautifully hand finished to the finest furniture standards using only premium matched, real-wood veneers, that's Monitor Audio … where art and science meet!

(Studio 10). . . "I found listening to this design to be an exhilarating experience bordering on intoxicating at times, and one that didn't pall."

--Hi-Fi Review (Feb. 90)

--------------------

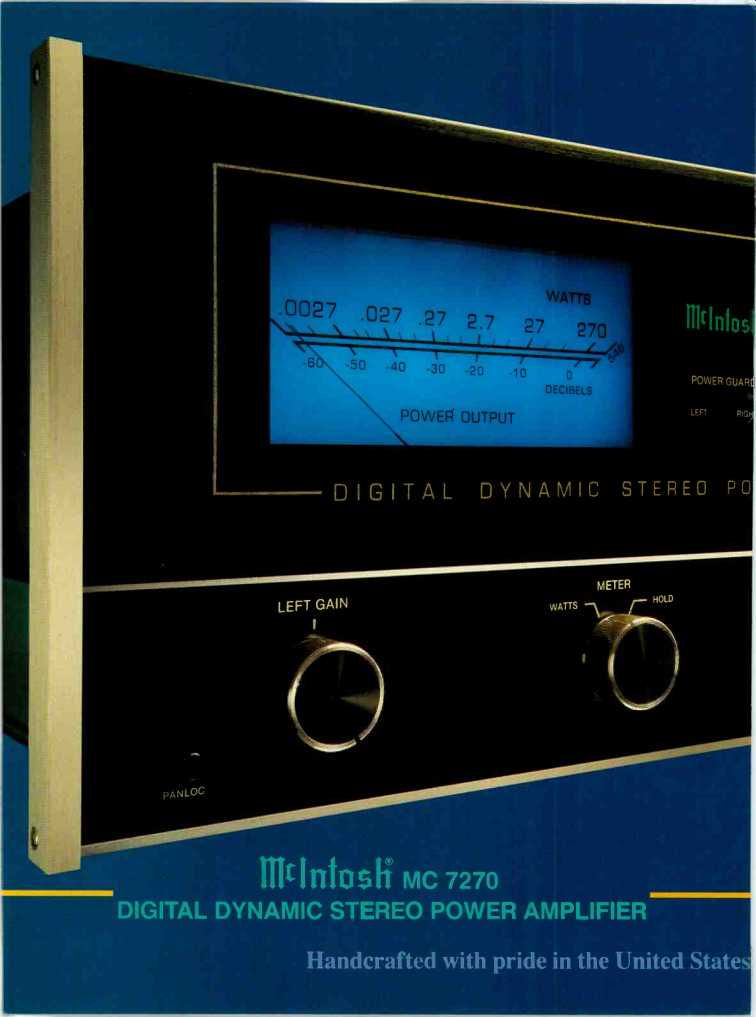

McIntosh MC 7270

DIGITAL DYNAMIC STEREO POWER AMPLIFIER

The McIntosh MC 7270 power amplifier is designed to fulfill Digital Dynamic Range demands. It outperforms all competitors when listening to sound derived from digitally recorded tapes and compact discs.

"That a manufacturer can remain faithful to a certain listening style, to a "sound signature" recognizable by all through electronics even so different always astonishes. Such is the case of McIntosh where, in spite of the change from tubes to transistors and from medium to high power, the basic McIntosh quality has not changed with the added benefit of an enormous reserve of power. Witness the MC 7270 for which this reserve of power sensation reaches almost the "colossal".* The compact disc is capable of real life dynamic range while noise generated from compact discs is inaudible.

With the noise restraint removed it is both easier and dramatically more enjoyable to listen to music at much louder levels. To fully enjoy this new capability your amplifier must be able to receive three to ten decibels of overstress from music, and it must do this without severely distorting the sound! This is the real world of Digital Dynamics demand. How to achieve the performance demanded, which often lasts from minutes to only a few thousandths of a second, and to achieve the goal economically, is a real achievement. Power Guard is that achievement.

"The Power Guard system is most effective in making it impossible to hard clip the output of the amplifier.

Regardless of how hard it is driven, it simply cannot develop an audible amount of distortion on musical program material. This feature should also mean a greatly reduced likelihood of blowing out a speaker, since clipping is a common cause of tweeter damage."** McIntosh leadership in engineering has developed the Power Guard circuit which

-(1) dynamically prevents power amplifiers from being overdriven into hard clipping

-(2) assures that the amplifier will produce its maximum output without increased distortion

-(3) protects your speaker from excessive heating. Power Guard is a patented McIntosh design ( U.S. patent #4,048,573).

"The feeling of power is never refuted and instead of stunning the listener, the 7270 recreates an audio environment of a majesty that no other transistor amplifier is capable of reproducing as well."*

For information on McIntosh products and product reviews please send your name, address and phone number to:

McIntosh Laboratory Inc.

Department A904B PO Box 96 East Side Station Binghamton, NY 13904-0096

---------------

Also see:

Build the Bassis--A CIRCUIT TO CORRECT AND EXTEND LOUDSPEAKER BASS RESPONSE (April 1990)

= = = =