by SUSAN ELLIOTT

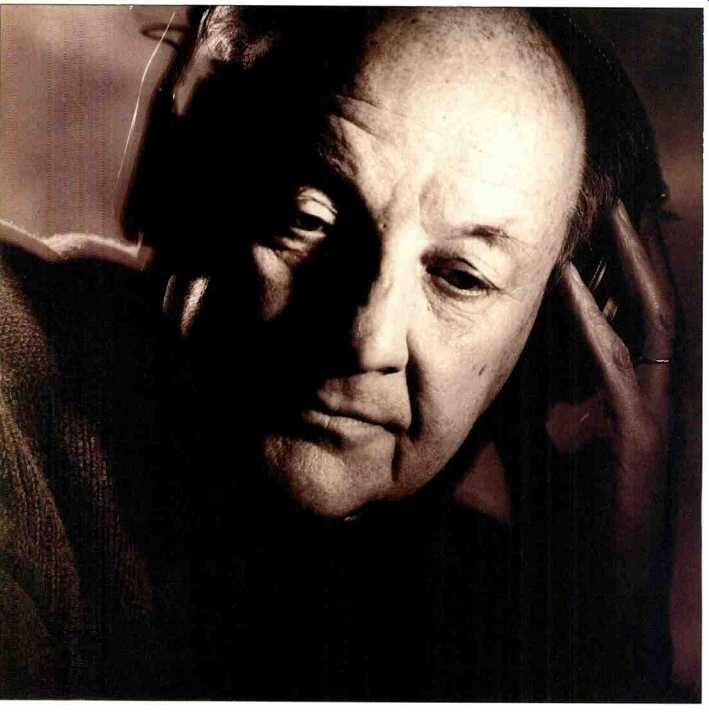

Thomas Frost is perhaps the most sought-after independent producer in the classical record industry today. His best-known client is the late Vladimir Horowitz, whose recordings he produced for Columbia Masterworks in the '60s and for Deutsche Grammophon and Sony Classical in the '80s.

Frost has recently signed on as a producer and consultant to Sony Classical; he will record, among others, the Berlin Philharmonic under Claudio Abbado, and supervise the CD reissue program of the CBS Masterworks vaults. Until recently, he had been consultant to Deutsche Grammophon, producing recordings by Kathleen Battle, Itzhak Perlman, the Emerson String Quartet, and others.

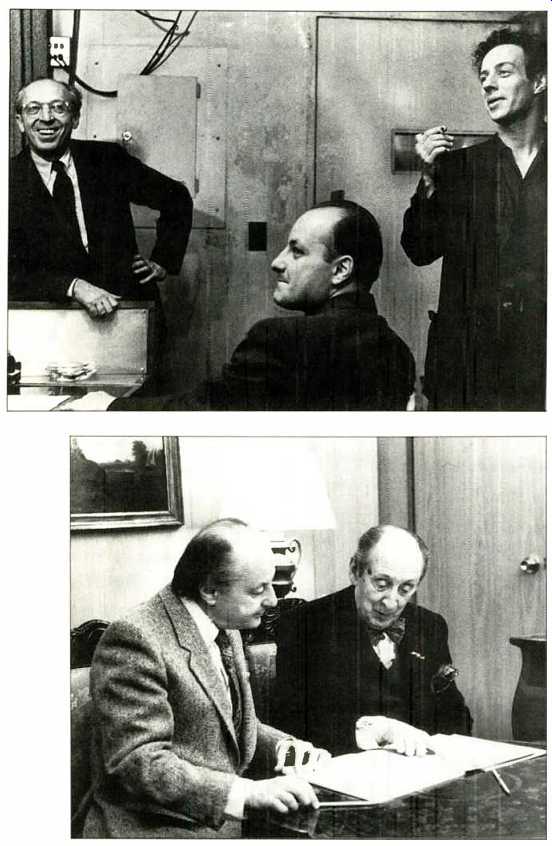

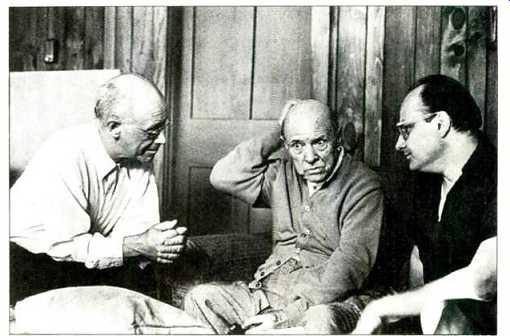

top: Aaron Copland, Tom Frost, and pianist William Masselos at

Frost's first Columbia recording session, 1959. Photograph: Courtesy Tom

Frost; © Fred Plaut. above: Frost and Vladimir Horowitz in Milan,

Italy, 1987, discussing Mozart's Piano Concerto No. 23. Photograph: Courtesy

Tom Frost; Silvia Lelli Masotti.

Born in Vienna, Austria, Frost began violin studies at age seven and sang for a time with the Vienna Choir Boys. Ile came to the U.S. in 1938 with his parents, and in 1947 enrolled at Yale University, where he studied with composer Paul Hindemith. In an exclusive interview, he talked about his career as a staff and independent producer, and about the last two Horowitz discs, both of which were recorded in the famed pianist's Manhattan living room.

How did you get into this business? Didn't you start out as a violinist?

Yes. I played violin in the New Haven Symphony while I was at Yale, but by the time I left, I had switched to viola.

When I came to New York in '51, I was able to get some assignments playing viola in Broadway pit orchestras. I also taught privately, but I still found it difficult to make a living.

At the time, I was a [viola] student of Lillian Fuchs, who recorded for American Decca. She knew something about the industry, and she told me there was a need for qualified musicians who could guide technicians in the recording and editing process. At this point, tape had been in use for only five years--everything had been direct-to-disc before then. So there was tremendous expansion going on in the industry.

How did you get in the door?

I actually found my first job in the New York Times. I was getting desperate, looking for anything. Finally I saw an ad, "Interesting job, Decca Records." Decca was very successful then; it had a great many popular artists, like Bing Crosby and Ella Fitzgerald. It was one of the first companies to do complete original-cast recordings.

The job turned out to be strictly clerical. The only "interesting" part was going to sessions to go over the AFM [American Federation of Musicians] contracts and making sure everyone had filled out the proper forms. The man who interviewed me said I was way overqualified, but I talked him into letting me have the job anyway.

I started in September of 1952. Three months later, there was a big shakeup, and they fired 50 people. I was on the list. Then Sy Rady, who ran the classical department, had the idea that I could replace one of the producers he was losing and continue in my old job at the same time. And all for $50 a week!

I learned how to edit from Eddie Remusat. I'm very grateful to him; he really showed me what could and couldn't be done with a razor blade. He now runs a small recording studio near 57th Street. I also learned a great deal from the head engineer of Decca, Charles Lauda. Within a few months, I was doing my own sessions. One of the first was Andrés Segovia.

Where did you record?

The ballroom of what was then called the Pythian Temple, on West 70th Street between Broadway and Columbus. It was a great hall--quite live, with a hardwood floor and ornate plaster surfaces. I'm still very fond of some of the records we made there.

Once you ran your own sessions, did they pay you more?

Yes, in a manner of speaking. Things were tight, and Sy felt guilty that he couldn't get me more money. So he arranged for me to play violin on pop sessions. I often made three or four times the amount of my salary in a given week, since I was getting union scale.

What was your style as a producer at this time?

I was a great perfectionist. I apparently had a very good ear. I would work the artists very hard, while at the same time attempting not to lose the musical excitement. There were a lot of retakes.

When did you leave Decca?

In 1957. I took six months off to study conducting with Leon Barzin. Conducting was always one of my dreams.

Then I found a job at Urania, a company started in the late '40s/early '50s. It had a catalog of mostly licensed material by European artists. Sig Barth bought the catalog and wanted to make new recordings as well. So he hired me as the A & R director.

Whom did you record for Urania ?

The Kansas City Philharmonic; Barbara Cook--we did a Rodgers and Hart recording called From the Heart of which I'm still very fond; I did the saxophone concertos of Glazunov and Ibert and hired Skitch Henderson to conduct. Just last summer he hired me to produce a New York Pops record.

Skitch introduced me to Schuyler Chapin, who was Skitch's manager at CAMI. [Chapin was former Metropolitan Opera General Manager and current Vice President of Concerts and Artists for Steinway & Sons.] When Schuyler later went to Columbia Masterworks, he called me. I came in as Associate Producer at the end of 1959.

Who was your immediate supervisor at Masterworks?

I reported to Schuyler, but John McClure assigned my daily chores.

John's title was music director. Columbia Records really felt like a small company back then. Goddard Lieberson was the president and Schuyler reported to him. Tom Shepard came in as a trainee shortly after I arrived.

We were at 799 7th Avenue. There was a recording studio on the top floor that was later bought by A & R Studios. And, of course, we had our own studios at 30th Street too.

above: Eugene Ormandy and Frost preparing to record Grofé's Grand

Canyon Suite with the Philadelphia Orchestra. Photograph: Courtesy Tom

Frost; Adrian Siegel.

above: Frost, Lucine Aymara, Richard Tucker, Eugene Ormandy, Maureen

Forrester, and George London at the Manhattan Center while rehearsing Verdi's

Requiem, circa 1966. Photograph: Courtesy Torn Frost; CO Adrian Siegel.

Which artists did you record ?

My first recordings were with Bruno Walter in Los Angeles. He was 83 or 84 at the time and had stopped performing publicly. The orchestra we used consisted of L.A. Philharmonic players and some of Hollywood's top studio musicians; we called it the Columbia Symphony Orchestra. The sessions were in the American Legion Hall in Hollywood, one of these wonderful, old-fashioned ballrooms with wood floors and plaster and balconies and all kinds of uneven surfaces that reflect the sound in all directions.

Later, I took over the Eugene Ormandy/Philadelphia Orchestra sessions; I probably produced about a hundred recordings with them until they switched to RCA in 1968. I also worked with George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra for about three years in the early '60s. I respected Szell but found him cold as a person, whereas Ormandy was very warm and was like a father to me.

Didn't you end up running Masterworks?

Yes. I had worked my way up to producer and then executive producer.

But I was not very popular in some circles. I was never known as a company man, since I often fought on the side of the artist when I felt that the business affairs department was being unfair.

Clive Davis had succeeded Goddard as president of Columbia Records, and when McClure left, Davis wasn't sure he wanted to give me the top job. At the same time, Tom Shepard made a pitch for it. So Clive proposed that Tom and I be co-directors of Masterworks. I agreed. This was in '73 or '74. Together, Tom and I signed Michael Tilson Thomas and Murray Perahia. Then Tom took the top position--at RCA Red Seal and I was left alone at Masterworks.

Which then put you in the top slot?

For a while. During the year we were co-directors, Clive was fired, and Goddard came back in as acting president. Goddard was never convinced I should have that job either. In the late '70s, he brought in Marvin Saines as Vice President of U.S. Masterworks, with the A & R Director-me-and Marketing Director under him. Saines was very difficult to work for; at least I man aged to get him to agree to signing [cellist] Yo-Yo Ma.

Then Masterworks was reorganized on an international basis. They wanted to revamp the whole department. In the spring of 1980, when I was in Salt Lake City recording the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, I got a call from personnel, offering me a three-year contract to make five records a year for a nice annua salary. And I said okay, because I was getting tired of having to fight fo everything I wanted.

Consultancies aside, you've essentially been independent ever since. How does that work? Do artists and labels come to you or vice versa?

It goes both ways. A label will approach me directly or an artist or organization will come to me and then I work out a proposal with a label. That's what happened for instance with the Yale Cellos [The Sound of Cellos], which was sold to Delos, and with Barbara Nissman's Prokofiev piano recording [The Nine Piano Sonatas], which is out on Newport Classic.

Or I'll get a call from, for instance, Bob Hurwitz at Nonesuch. I brought the Kronos Quartet to Nonesuch and produced their first record for the label.

How do you get paid?

Companies generally pay me a flat fee.

The only time I get a royalty is when an artist comes to me and I make the deal with the label. In that case, I'll keep 20 percent of the royalties and pay the artist 80 percent. I got very high--I mean unprecedented--fees for Horowitz's last two recordings.

What was your arrangement with DG ?

I had a nonexclusive contract as a consultant. I coordinated the details of some of their U.S. recordings, including the Met "Ring and [DG] projects with the New York Philharmonic, Boston Symphony, and Chicago Symphony. My contract ended last October when I entered into an agreement with Sony Classical.

Aren't you producing some DG artists?

I'm still working on my second record with the Emerson String Quartet; the Carnegie Hall spirituals concert that we recorded last April with Kathleen Battle, Jessye Norman, and James Levine, and a cello/piano record with Matt Haimovitz and Levine.

In watching you record the Emerson Quartet, I thought you, at times, were more aggressive musically than many producers. You almost functioned as a music director, giving them tempo suggestions and so on.

I had very good musical training and I came out of that with strong opinions.

Not that I want to force my views on a musician, but having studied composition and theory and having analyzed things backwards and forwards all those years, I know how music is constructed. Some artists are negligent in the aspects of interpretation that have to do with balance and clarity. So I'll make specific suggestions in that area.

If the artist chooses to reject them, that's his prerogative.

Some producers say it's none of my business. They would never tell an artist that a tempo is too fast or too slow or there's too much rubato. They take it down as it's played. But I feel it is in the interest of the record for a producer to act as a critic, musically speaking.

Kathleen Battle has a reputation for being a real prima donna. How does she respond to your approach?

She welcomes any and all suggestions. In fact, after our first sessions together, she told me she wanted more input from me, that I should be 'brutally frank." And now, at least for the moment, I seem to be one of her favorite producers.

How have other artists responded?

Ormandy was very grateful for suggestions, whereas I couldn't tell Szell anything; I don't think he would admit that any producer knew enough to tell him anything. I never worked with Bernstein in my days at Columbia, but I visited some of his sessions. He seemed to want the producer to be completely passive and just concentrate on the sound. Some conductors are that way.

How about Horowitz?

I had to feel my way with him. He asked my opinion some of the time. but in his case, it was more in the editing that I used my expertise. He played complete pieces and movements and didn't worry about mistakes. He didn't like to work in small sections. So we'd have five or six performances of a whole piece, each one played very differently--faster, slower, different rubato, different pedaling-because he was so spontaneous and imaginative. Making it all into a unified performance was a big job.

above: Rudolf Serkin, Pablo Casals, and Frost at tlu' Marlboro

Musco Festival in Vermont. Photograph: Courtesy Tom Frost; e Fred Plaut.

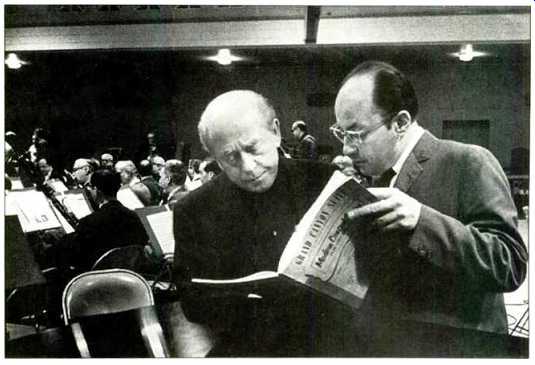

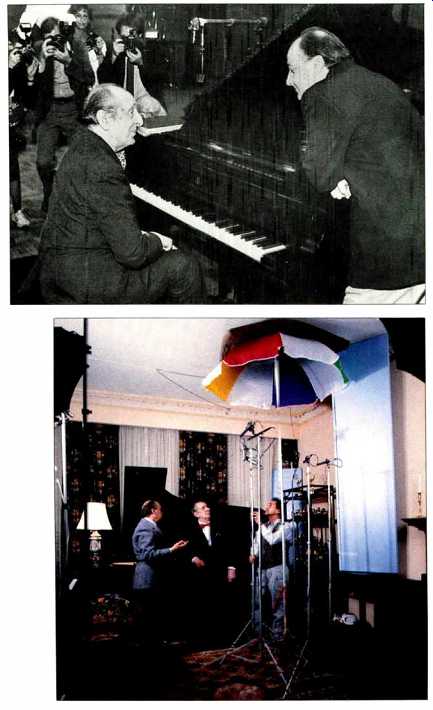

top: Vladimir Horowitz and Frost at RCA Studios New York City,

1986. Photograph: Courtesy Tom Frost. above: Frost, Horowitz,

and engineer Tom Lazarus during the first recordings at Horowitz' home.

Photograph: Courtesy Tom Frost; C Christian Steiner.

How many Horowitz recordings did you do?

About 15 altogether. I made 10 records with him at CBS, starting with his first in 1962. In the last five years, I did five, the more recent of which was The Last Recording for Sony. Before that, on DG, we had Studio Recordings, 1985, Horowitz In Moscow, the Mozart A Major Concerto [K488], and Horowitz at Home.

His last two discs were recorded in his living room in Manhattan. That must have been a challenge.

The difficulty was getting a satisfying piano sound in a small, confined space. What tells the mind that it's a small space are the very quick reflections. That sound, whether it's solo violin, flute, or piano, is tolerable in person, but not on a recording.

So our aim was to avoid reflections. Tom Lazarus, my engineer, decided we'd have to damp down the room. But we couldn't overdo it, because it would become dead, which was bad for the recording and unpleasant for Horowitz while performing.

So we covered the window glass with Sonex-pure glass is very reflective, especially [in] the high frequencies-which also shut out any sound coming in from the street, and over the large mirror opposite the piano.

On the walls we used composition board, which is partially, as opposed to totally, absorptive. Horowitz was happy with these adjustments, since he felt that the room was a little too live with the piano lid open. He usually played with it closed.

The ceiling was another problem: With the lid open, a lot of the sound travelled up there and came right back down again. So Tom invented an ingenious way of holding two pieces of Sonex against the ceiling without gluing them. (That would have been vetoed by Mrs. Horowitz anyway.) He mounted two beach umbrellas on top of tall microphone stands and placed a 4-by-4 foot piece of Sonex on top of each of the umbrellas. Then, Tom simply raised the stands until the umbrellas squeezed the Sonex up against the ceiling.

By the way, we cut our own stick for the piano, about 12 inches longer than the normal stick. That reduced reflections from the lid into the mikes. And because the lid was more open than usual, we got more direct and less lid reflected sound. Of course, we had to be careful not to be too close, because then the sound would be ugly and percussive.

Where were the mikes?

In all the piano recordings I do, the microphones are, depending on the acoustics of the room, three to ten feet away from the keyboard, horizontally.

In this case they were three feet away and about eight feet high.

How were they mounted?

Tom put push pins into the molding near the ceiling and stretched a very thin fish line from one end of the room to the other. This supported the two microphones. One was near the far end of the piano, picking up bass frequencies, and one was toward the hammers, where more treble is produced. We used two omni Schoeps Collette series microphones.

Was there a difference in the installation between Horowitz at Home and The Last Recording?

No. The main difference was in the use of digital reverb after editing. I wanted to be very literal in the first record so I added just a tiny bit of reverb to get a pleasant, intimate "at home" sound.

With The Last Recording I felt I could be freer in enhancing the sound. I wanted to create the illusion of a small concert hall rather than a large living room. So we used more reverb and got a richer, more sumptuous sound.

Frankly I like it better.

What tape machine did you use?

On the DG recording, we used a Sony professional DAT machine that was modified with Apogee filters by Gotham Audio. DAT machines are very handy for a number of reasons. One, because they hold two hours of music; on the Sony U-Matic system you have to change every hour. Two, the indexing capability makes it easy to find takes quickly.

Did you use a professional DAT on The Last Recording as well?

No, Sony wanted me to use its new 20 bit system, which uses a two-track reel-to-reel machine and quarter-inch tape. The extra bits give wider dynamic range and therefore make the recording quieter, although the difference is barely audible. I did use a pro DAT as well, for reference.

Do you usually record two-track?

Most of the sessions I've done since leaving CBS have been two-track, including orchestras. It can be nerve-racking because you can't remix anything; you have to get all the balances correct from the start.

Why go through that?

Because multi-track is more time consuming and because I like the challenge of getting it right in the first place instead of "fixing it in the mix." When you have a good hall and orchestra, you can get excellent results on two tracks. On the other hand, for live concerts and music that has additional elements-soloists, chorus, etc.--it's safer and in some cases essential to record multi-track.

To what extent do you get involved in engineering?

A recording should reflect my taste in every respect. I'm responsible for the sound, so I take an active part in sound quality and balance. This does not follow the German system, where the engineer is responsible for sound and balance and the recording director is responsible strictly for musical performances. That's very limiting. I don't like the idea of being at the mercy of an engineer.

Would you always rather record in a hall than a studio?

I've never found a studio that is ideal for classical recording, including Columbia's old 30th Street studio. That was a multi-purpose studio that gave you fairly good results for a lot of different situations, but it had certain shortcomings--it could be too dry.

What's your favorite hall for recording ?

Kingsway Hall in London. You could put up microphones almost anywhere and it sounded good. It's not operative anymore. I also liked the American Legion Hall in Hollywood, where I did the Bruno Walter recordings; Boston Symphony Hall, and Carnegie Hall, except for the subway rumble.

Given all the modifications it took to turn Horowitz's living room into a decent environment for recording, why did you record him at home?

I actually resisted the idea for a long time. But I was beginning to see there would be no recording at all if we at least didn't try it at home.

Of course, it was much more convenient for him--if he didn't feel like playing one day he could just call me up and cancel. Whereas if we had booked RCA Studios, where he recorded the first DG disc, cancelling was awkward.

Besides, he never liked the trip downtown through traffic before a session.

As you look back over your career, what projects have been the most rewarding?

Certainly Horowitz, the Ormandy recordings, Bruno Walter, Rudolf Serkin, Pablo Casals conducting the Marlboro Orchestra. There are really too many to pinpoint.

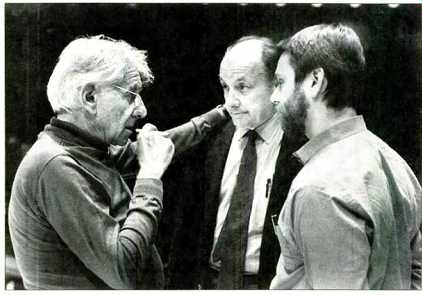

above: Leonard Bernstein, Frost, and engineer Daryl Bornstein at

the Music For Life concert, Carnegie hall, 1987.

(adapted from: Audio magazine, Apr. 1991)

= = = =

Also see:

The Audio Interview: Emory Cook--First Take (Sept. 1989)

Link | --The Audio Interview: Jack Pfeiffer--RCA's Prince Charming (Nov. 1992)