by Bob Gary

In the '20s, one of the winningest racing cars around was the classic Bentley 41 liter, an incredible 22 feet of car fitted with two spare tires, three huge tool boxes, and seating for five.

To most observers today, the Bentley seems more truck than sports car; yet it scored the first British victory at Le Mans and countless other racing triumphs. Obviously, the old 41 would not be much of a competitor in con temporary racing, as the cars have been improved, aerodynamics, suspension geometry, and a host of other factors have become increasingly important, to the extent that, now, even the shape of the side mirrors affects a car's performance.

A similar phenomenon has occurred in the field of audio design; factors which at one time were inconsequential, masked by larger faults in other parts of the equipment, are now of critical importance, given the improved sonic definition of modern music systems. The clearest example of this is in the turntable-cartridge combination which serves as the primary music source in most systems. A series of developments since World War II have vastly improved the ability of a turntable to extract musical information from records: magnetic cartridges, the offset tonearm, and standardization of tracking angle. Yet the record playing system remains a very weak link in the audio chain and one most easily affected. The positioning of the cartridge in the arm, the construction of the headshell, the length and type of connecting cable, and even the mounting screws used, all have a real and audible effect upon the ultimate listening qualities of the system. More than any other component, the turntable-cartridge combination requires a process of testing and adjustment, of "tuning," as it were, to realize optimum performance.

Among the most common problems affecting turntable-cartridge combinations is that of the "arm-cartridge resonance" engendering bass coloration and distortion. All tonearm and cartridge combinations have a resonance or range of tones which will be accentuated by the mechanical properties of the combination. The frequency range in which this accentuation occurs is determined by the compliance, or degree of looseness, of the stylus assembly (which is in turn ordinarily deter mined by the rubber collar which holds the stylus) and by the dynamic or moving mass of the arm (which is controlled primarily by the location and physical weight of the headshell and cartridge). If this resonance occurs at too high a frequency, say about 20 Hz, the deep bass information in the music will be muddied by the bass accentuation. If it occurs at too low a frequency, the effects of motor rumble and record warps will be greatly increased, and bass articulation will again be reduced. This is because the cartridge and preamplifier will interpret the warp and rumble information as music, and due to the accentuation caused by the arm-cartridge resonance, reproduce these subsonic tones at very high level, overloading the power amplifier and loudspeakers. In one case, ' Advent and Apt Engineer Tomlinson Holman found that a particularly poorly matched tonearm and cartridge were actually overloading the input of a tape recorder so severely that the unit was shutting itself off. In most cases, the effects are not that marked, but many systems suffer from arm-cartridge resonance problems to the extent that more of the amplifier's total power is being used to reproduce the warp and rumble than to play back the music itself.

To test for resonance problems in your system, first put a record which has proven itself difficult to track on the turntable, and play the first track.

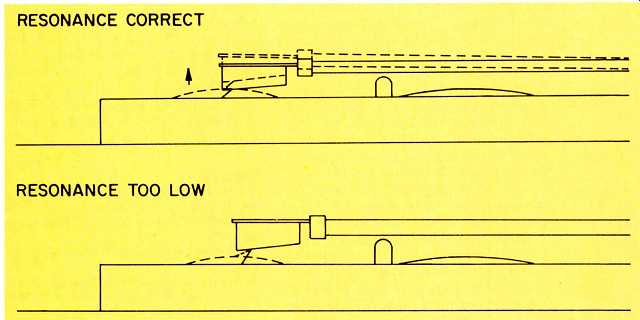

If the entire arm moves up and down over the warps, without any independent wiggling of the stylus, the arm-cartridge resonance is probably neither too high nor too low, but in the proper middle region. If the stylus itself wiggles up and down as it moves over the warp, while the arm remains stationary, the resonance is at too low a frequency. Resonance at too high a frequency is rare, particularly given the current crop of high-compliance cartridges. It may be tested for by putting a penny on top of the headshell, and listening to a bass-oriented selection a number of times, with and without the penny. If the presence of the penny seems to reduce artificial mid-bass warmth, substitute a small headshell weight, available from your dealer.

The new Shure TTR-115 test record also contains a band designed to check for arm-cartridge resonance problems.

There are two general methods of solving the more prevalent problem of too low a resonance: One is to arrange for the resonance to occur at a frequency above the problem frequency region; most engineers view 10 to 12 Hz as the ideal resonance frequency region. Since the compliance of the cartridge cannot be changed, the only practical means of raising the resonance frequency into this proper range is to reduce the moving mass of the arm, by removing relatively unneeded parts, such as finger-lifts and stylus guards, or by reducing the mass of those parts which must remain, using nylon, rather than steel, mounting screws (these are available at many hobby stores), and, in severe cases, by trimming away unnecessary parts of the headshell or replacing it entirely with one of lighter weight.

The other method, particularly in cases where mass reduction proves ineffective, is to damp out the resonance so that it introduces very little, if any, accentuation, and is therefore inaudible. A number of firms make devices for this purpose; Shure has one as an integral part of their V-15 Type IV phono cartridge and Discwasher makes a unit, the "Disctraker," which is usable with any tonearm. Depending upon the design of the pivot bearings, some arm-cartridge combinations may be damped by the injection of a silicone gel (10,000 centistoke viscosity is about right, for those who would like to experiment) into the vertical pivot, though this can also introduce undesirable side effects. A few home brew audiophiles, and at least one manufacturer, have developed systems which use open pools of liquid and paddles to reduce resonant motion.

Another major variable is that of the loading presented to the phono cartridge by the connective cables and the preamplifier. All cartridge manufacturers design their products to operate with a certain "load," or set of conditions inside the first stage of the preamplifier, which will assure flat response. The load is composed of two properties: A resistance, which for modern cartridges has been standardized at 47,000 ohms, and a capacitance, which is not standard and may, in fact, be specified for different cartridges over a wide range of values. If the capacitance provided by the preamp and cables is different from the value recommended by the manufacturer, the response of the system will not be flat in the mid and upper treble. This usually has the audible effect of exaggerating surface noise and record "pops" and may also make the system sound somewhat harsh or metallic on brass instruments and voice, in particular. In the early days of hi fi, these effects were masked by the poor treble response of most loudspeakers.

In modern systems, however, where an enormous amount of research has gone into achieving linear response in the amplifier and loudspeakers, a 3-dB variation in treble response represents a serious defect in performance. At least one design engineer, Tom Holman, has advanced the theory that the differences heard between high quality preamplifiers and integrated amplifiers are caused by variations in frequency response because of capacitive effects, rather than by reasonable levels of distortion products.° Because different preamps and turntable connecting cables supply different quantities of capacitance, for years the only practical way to match up the turntable, amp, and cartridge for flat response was to take the whole shebang to an audio service shop, have the system tested, and then add the amount of capacitance needed, either in a minibox or by soldering the necessary components directly into the circuit. This was, of course, a fairly expensive operation.

Fig.

1--When checking arm/cartridge resonance, if the entire tonearm assembly

moves up and down over warps without wiggling, resonance is in the proper

middle region. However, if the stylus alone moves up and down, the resonance

is too low thereby increasing the effects of record warp. RESONANCE CORRECT

vs. RESONANCE TOO LOW

Recently, however, a number of manufacturers have introduced preamps which incorporate selectable input capacitance. Another solution for the average system owner is the development by Discwasher, db Systems, and Berkshire of capacitance adaptor systems compatible with any amplifier and turntable, which are connected between the turntable cables and the input jacks. Discwasher includes a comprehensive chart, which cross references amp, turntable, and cartridge characteristics, for selection of the precise value for flat response.

A series of small adjustments also have surprisingly large effects upon the sound quality of a system: Even slight inaccuracies in the geometry of cartridge mounting will substantially increase tracking error distortion. It is consequently very important to align the cartridge with the mounting guide or template with extreme care, even though the process may take 20 minutes or so. A British author, J.K. Steven son, has calculated that a 0.2-in. or two degree error in mounting position will double the harmonic distortion figure of a typical turntable cartridge combi nation, to almost 2 percent.' This level of distortion is about one hundred times larger than that of the best cur rent amplifiers, so this step is certainly worth the effort.

Both tracking force and anti-skate settings are worthy of careful adjustment, too. The fashion in tracking-force settings today is to utilize the smallest force necessary to keep the stylus in the groove. Very low tracking forces are generally inadvisable for two reasons. Most importantly, low tracking forces generally do not eliminate record wear, but actually increase it due to mistracking. Also, distortion caused by mistracking is enormously reduced as the tracking force is increased. In fact, the published distortion figures for most cartridges are usually measured with tracking forces from the upper end of the manufacturers' recommendations. The optimal tracking force, from the standpoint of both wear and distortion, is in the middle of the cartridge manufacturers' range of recommended forces, very rarely below 1.5 grams.

Anti-skating settings are at best an approximation, since the forces which draw the arm inward are constantly changing, but certain steps can be taken to achieve a more precise adjustment. For this an unmodulated disc (one which has a totally blank, groove-less section) is required. Shure presently makes one, and some dealers may still have an old Garrard unmodulated disc lying about. To make the adjustment, the disc is put on the turntable, and the arm cued to the blank section. The turntables' anti-skating force control is then adjusted such that the arm remains motionless as it tracks the blank portion. This indicates that the inward skating force is counterbalanced by the anti-skating mechanism of the turntable, and the adjustment is correct. An adjustment made in this manner will be at about the minimum level since skating force developed by playing of the blank disc is substantially less than that from playing heavily modulated grooves.

Other points of importance in the tuning process are concerned with the signal path from turntable to preamp. Given the low intrinsic noise figures of modern amplifiers, any audible hum or hiss while playing records is indicative of something gone awry, usually in the signal path. Hum or noise could be the result of loose, corroded, or defective cables or jacks or a loose or broken ground lead. Connectors may be cleaned with an abrasive pen eraser. When cables are internally defective, quality molded replacements are in order. If all of these possibilities are checked and the problem still persists, the system may be suffering from some sort of ground loop. Experiment with connecting the receiver's ground lug to a solid-earth ground (the center screw of a wall outlet, for instance) or try disconnecting the turntable's ground lead from the receiver. Any arrangement which eliminates the hum is acceptable. In certain instances, a turntable cable in close proximity to a line cord may induce hum; check to be sure that cables are kept separate. With low-output moving-coil cartridges or when cables must be placed close together, it is sometimes effective to wrap each cable in aluminum foil.

Feedback from the loudspeakers to the turntable may introduce bass coloration. The best test for this is to tap the turntable surface while playing a record with the volume level as high as you ever use. There will, almost certainly, be a "thump" from the loudspeaker, but if the thump is ac companied by any ringing or shriek, the system is susceptible to feedback troubles. Moving the turntable to a place less affected by the bass information in the music is the simplest solution, though in certain stubborn cases it may be necessary to mount the turntable on a separate platform or on anti-resonant feet, such as those made by Audio-Technica.

Audio hobbyists, like the people who race cars, are continually seeking just a bit more performance from their equipment. Sometimes the price of excellence is very high; the point of diminishing returns is a concept that enters into most music system purchases. But it is also true that remarkable improvements in sonic performance can often be obtained just by matching and tuning the equipment. Even the of Bentley benefitted from a tuning now and then.

References

1) Tomlinson Holman, "New Tests for Preamplifiers," Audio, February, 1977.

2) J. Brinton, “Tonearm Damping," High Fidelity, July, 1975.

3) SME/Shure 3009 Series III tonearm with "fluid bath."

4) Tomlinson Holman, "New Factors in Phonograph Preamplifier Design," Journal of the Audio Engineering Society, May, 1976.

5) J.K. Stevenson, "Pickup Arm Design--I," Wireless World, May, 1966.

(Adapted from: Audio magazine, Jun. 1979)

Also see:

Do Turntable Mats Work? You Bet! (Jun. 1979)

Understanding Phono Cartridges (March 1979)

= = = =