by TOM BINGHAM

Syndicated shows such as the "King Biscuit Flour Hour" and "A Prairie Home Companion" prove the resurgence of interest in listening-truly listening-to radio programs rather than the drone of formatted tapes offering background music.

One of the prime movers in radio's new sound is the subject of this interview, recordist par excellence Jim Metzner.

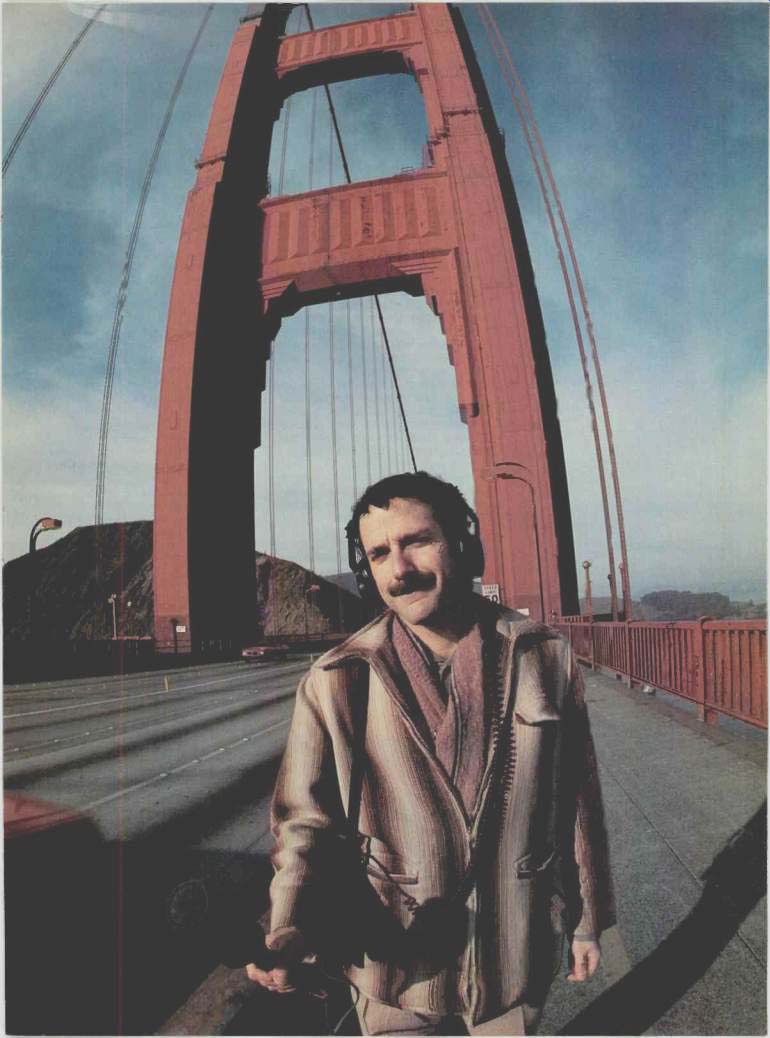

above: Jim Metzner captures the sounds of San Francisco's Golden Gate

Bridge.

"Radio is a listener's medium, where the listener really can be included. Television gives you everything and becomes a passive medium. As a listener's medium, radio interests me; the act of listening interests me. And as a sound recordist, I have the opportunity to go out and rediscover the experience of listening.

"Every so often I am witness to an extraordinary sound, a moment in sound. On such occasions there is a wish to share this moment in sound, to communicate it to others. It may be something as simple as the sound of somebody's voice. Maybe I'm talking to an old person, or someone who sings a song with real feeling. It's the feeling in that person's voice, the way they're telling a story that begs to be shared. It demands to be heard by other people.

"I put my microphones on a boccie court. Through your ears you literally become a witness to this boccie game, almost a participant. You're surrounded by the game-the laughter of the players, the rhythm of their speech, the way they respond to the game. You become caught up in the excitement, the humor, the feeling, the gusto. That kind of subtlety, that kind of intimacy is rare in TV because a television crew with all its equipment usually destroys the delicate, subtle quality of this kind of moment."

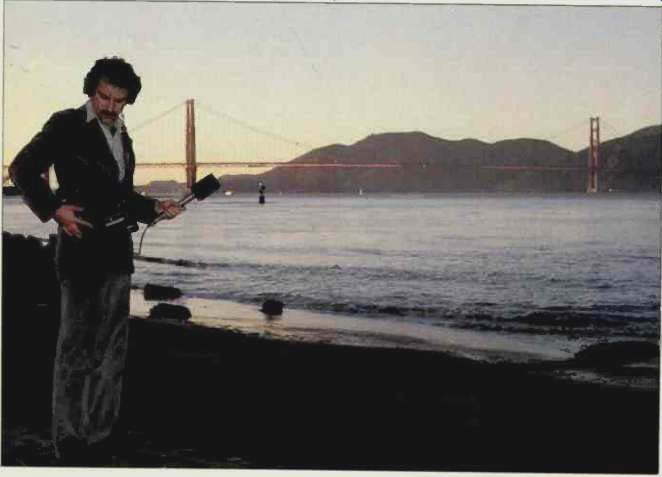

above: Armed with his Sony 989 mike, Metzner checks his tape recorder

before seeking to get the sounds of the Bay Shore for "You're Hearing

America."

--------

You are listening to Jim Metzner, a high priest of the aural arts, whose new show "You're Hearing America" is surely one of the freshest, most innovative things to spice the renaissance of radio. Now airing in a few selected major markets (see box for details), "You're Hearing America" is an imaginative blend of sound, music and narration packed into daily, two-minute segments that are entertaining, informative and even revelatory. The shows combine the actual sounds of an event in progress, a natural phenomenon or a machine with brief comments or reminiscences by people close to these sounds. Appropriate music may be added, and Metzner himself contributes a short narration. One program might concern Chicago street vendors, another the sounds of rodeo, a third San Francisco cable cars.

"You're Hearing America" dates back to 1979 when Metzner began producing its forerunner, the Gabriel Award winning local program "You're Hearing Boston." Metzner recalls the birth of the idea: "I had been recording the sounds of Boston for years. I had all these sounds and something was cooking. One spring day I was sitting in my apartment and through the open window I heard the sounds of a horse on the street. It had to be a policeman; they're the only people riding horses around Boston. I grabbed my tape recorder and under some pretext started recording the horse's hooves and footsteps. I forget how I explained myself to the policeman. Then I started talking to him about being a policeman on horseback. Something clicked inside.

'Of course, that's it! It's going to be a radio show about all these sounds and how extraordinarily interesting they are.' I don't think I've even used the policeman on horseback in a show, believe it or not.

"The idea sprang from the 'dimensionality' of sound, the 3D aspect when you record in stereo and then listen to the sound or play it back to someone with earphones. One is tempted to use the words 'captured' or 'got,' very greedy kinds of words. I 'captured' this moment in sound, I 'got' it on tape. What you actually have is a very pale reflection of the life of a moment. It is like dropping a stone in a pond; what you have is maybe the second or third wave of ripples. But it's still something that can touch us if the listener is willing to enter into the spirit of the recording." Convinced of the worth of the idea, Metzner sought an outlet. "I did a program on spec and took it to WEEI-FM, a local soft-rock station whose format and music I liked. I had considered the context, I tried to remember that people would be listening to music both before and after the show. I wanted my program to be compatible. I gave the station a bite-sized, digestible chunk.

"After certain suggestions from WEEI-FM I came up with a two-minute program. The station found a sponsor and I had a radio show. The program director at WEEI-FM took a certain risk.

It was something new, something a little different. I think we were a success. The show was on the air about two years and we did perhaps 250 of them. People became used to the idea that around 3:00 in the afternoon there'd be this little moment in sound. You didn't quite know what it'd be from day to day." Following a move to San Francisco, Metzner began producing "You're Hearing San Francisco" for KYUU. At the same time he was preparing the national version of "You're Hearing America," which debuted in April under the sponsorship of Maxell Corp. In the national series, which sticks to the two-minute format, Metzner works with a number of independent producers from around the country.

"For the local shows," says Metzner, "I got in the habit of reading the newspapers, keeping my eyes open. People would come to me with ideas.

Sometimes I might just go out with a recorder, ready for anything. With the national series it's altogether different.

We're working with a community of independent producers that I think can be a real force in radio. They've been heard to a certain extent in noncommercial radio. They'll be heard more on commercial radio, and it's a group of people who really deserve to be heard-Jay Allison in New York; the Kitchen Sisters, David Nelson and Nicki Silva in Santa Cruz; a fellow named John Rieger in the San Francisco area. There are many others." Much of the initial production and editing is done by the producers themselves, who then send the material to Metzner for final production, fine tuning and the voice-over. "We give the producers a lot of feedback and suggestions on recording techniques and interviewing", says Metzner. "If anyone reading this article is interested in producing for the series or has ideas for the show, they can write to us, Sound Image, 533 Diamond Street, San Francisco, Cal. 94114." The style of the show excludes the voice of the interviewer. This can be tricky and as Metzner explains, "The interviewer somehow must be coaxed or instructed to speak in complete sentences that become the narration for the body of the program. We like to get the person to say what he or she hears. Listeners then hear through this individual's ears. For example, a mechanic who tunes up cars uses his sense of hearing. He'll say, 'Hear that ping, ping, ping noise? Well, that's a faulty piston.' Suddenly, we listeners hear the ping, ping, ping noise too.

Through the ears of another person you become more sensitive to what's there in the way of sound." Over the years, Metzner has experimented with a variety of gear. "The prime tape recorder I use now is a Sony TCD5M. Before that I used a Nakamichi 550. It's a great machine but really bulky. The 5M is very good. You need to monitor the levels on it carefully, at least on the one I use in the field.

Otherwise it distorts, although it's less of a problem with metal tape. I use either Maxell UD-XL II tape or a new bit of formulation now, XL II-S, which is very good, or metal tape. The 5M with either the XL II-S or Maxell MX metal tape is hard to beat, very good signal-to-noise ratio.

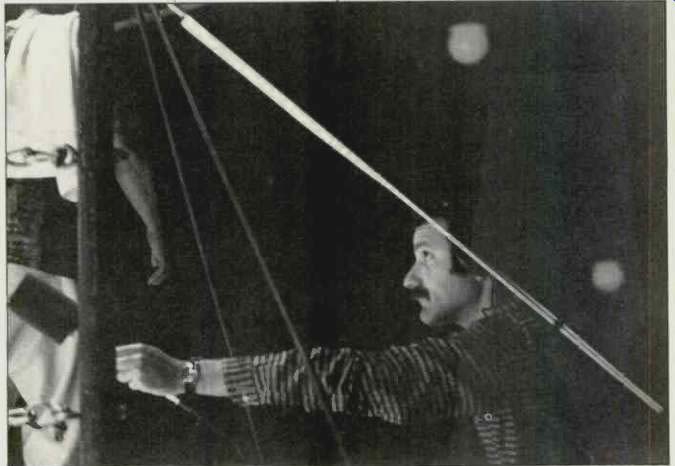

above: At ringside, Metzner thrusts his mike forward to record the

last words as a boxer's trainer leaves the fight zone.

"I use a Sony 989 microphone. It's a single-point-source stereo microphone with an MS pattern. The nice thing is you can adjust the polarity, the pattern of the microphone, from a fairly straight-ahead cardioid pattern to a spread of 90° between microphone capsules. If you put on earphones and then operate the little control, it's as if you were spreading a pair of microphones apart 90°, 120° and finally 150°. That's what it sounds like. Actually, I think you're adjusting the balance between a cardioid and a figure-eight pattern inside the microphone.

"I use the 0° setting for an interview, the 90° for a conversation, a small musical performance or an event that has a relatively narrow field of focus. For a bigger musical ensemble or an occurrence that involves a larger field of focus, say the size of a room, I'll go to 120°. If I'm in an airplane hangar or a symphony hall or someplace where I want a feeling of the largeness of the space, I use the 150° setting.

"My earphones provide relative isolation. I hear only what the mike gets: little outside sound reaches my ears." Occasionally, even a purist like Metzner must compromise. A problem was an attempt to record a rodeo calf roping contest. "The calves leave this chute quickly followed by two riders, a header and a heeler. One of them ropes the calf from the head, the other from behind," recalls Metzner. "There are several sounds, the chute opening, galloping horses, the twirling lasso, finally roping the calf. It was impossible to get on a horse and follow closely without getting in the way of the event. That was one of the rare times I've had to 'create' the sound. I recorded all the different pieces, the sound of the chute, the horses, lassoing-the lasso makes a kind of shoo woo-woo sound as it goes through the air. I pieced them all together but the result sounded like you were on that horse, lassoing that calf." Short as the shows are, they demand an enormous amount of Metzner's energy and time. "For a two minute spot I record an average of 40 minutes of field stuff. Then I listen to every bit, notating it. I have my own rating system of stars and asterisks for a particular sound, sentence or phrase that really stands out. With notation completed, there's a skeleton of a script in my mind. Then I can try to come up with what needs to be said to set the context or give the flavor. The script itself takes maybe an hour to write.

"The requirements of the premix depend upon the show. Some I can whip up right there, within an hour or perhaps two. For the final mix I work in four tracks although I'm in the process of switching to eight now. I bounce tracks á lot. For example, a track for narration may be mono and I'll have a stereo program and want to mix in another stereo piece. I've got five tracks right there. How do I do that on a four track machine? The answer is to bounce tracks. Final mixes can require an hour or much longer.

"On my voice in the studio I have a Sony electret condenser microphone, an ECM56F. It's a cardioid pattern microphone, a studio mike. In the studio I use a Sound Workshop 1280 board. I have a TEAC 3440 four-track recorder and a TEAC two-track, 3300SX. I also have an Otari two-track MX5050B2HD, and I just got an Otari eight-track, one from the 5050 series, which solved my bouncing-of-tracks situation. I have two dbx 150s on my multi-track. With the eight-track I've added more dbx units for simultaneous encoder-decoder noise reduction. They're nice because you don't have to keep punching them in when you're recording. I leave them in the in position when I want the dbx in, kind of forget about them once they're calibrated.

"I use a Dyna-mite as a limiter, as an expander and as a de-esser. It can also do noise gating, frequency-selective expansion, keying and ducking but I don't have a need for those functions. Other gear includes a Sony PSLX2 turntable and two Reference 208L speakers. The program goes to the stations on Maxell 35-90B reel-to-reel tape. My latest addition is an Orban 674A paragraphic equalizer.

"Sometimes I use a little EQ and limiting on the sounds if they seem to need it. We mix all over the place. The two minutes don't just happen. It's a matter of blending a number of moments to give an impression. I hope you don't hear the mix. That's the hallmark of a good mix; you don't hear it." In an era when video seems to dominate, Jim Metzner is demonstrating that radio devoted to the art of listening is still alive and thriving.

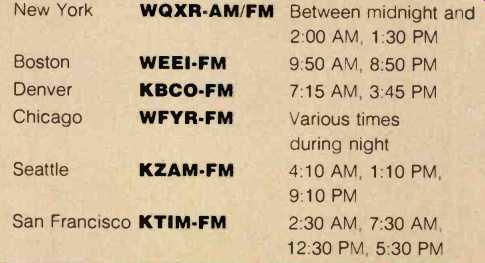

above: Where to Catch "You're Hearing America"

=============

(Adapted from: Audio magazine, Jul. 1982)

Also see:

Basics of Tape Performance (Sept. 1982)

= = = =