by David Lander

Classical music lovers have been applauding E. Alan Silver's recordings for more than a quarter-century. When Silver founded Connoisseur Society in 1961, he brought what is perhaps the ideal background to the primarily classical record company: A former musician, his first job in the record business had been listening to test pressings to determine if their surfaces were quiet enough. Later, during four years of consulting work, Silver and his partners produced records for several firms; they were responsible for three or four dozen titles that launched Kapp's classical division. Then came Connoisseur Society, which soon became well known for the caliber of artists it attracted and for the high quality of its discs. Silver's recordings on the Connoisseur label won him a bushel of honors, ranging from France's Grand Prix du Disque to a couple of Grammy nominations.

In the late 1970s, when the record business softened, the veteran producer switched formats and began mastering real-time cassettes on the In Sync Laboratories label. Recently, he has added luster to his catalog with historical restorations, made primarily from 78s, of great performances dating as far hack as the late 1920s. Two recent releases of' which he's particularly proud feature one of' the century's greatest cellists, Emanuel Feuermann, playing at Carnegie Hall shortly before his death in 1942.

-D.L.

-- -- -- --

You've recorded a great deal of piano music over the years. Has this been simply a matter of personal taste?

Yes, it has. It's also a matter of what we could afford and what I felt I knew best. I was a pianist, and I felt that if I heard something that was good, my judgment was accurate enough so that others would agree. I felt comfortable working with pianists.

Many of them were young and virtually unknown. The Brazilian pianist Joao Carlos Martins was in his mid-20s when you recorded him, wasn't he?

Right. He was 25.

Did he have any reputation at all?

He came here, played with the Washington National Symphony, and got spectacular reviews. We went to find him-on the basis of the reviews--to hear what this was about. And we missed him, by days. We didn't know where he was. We didn't know how to reach him or who his manager was, so when he disappeared he was just gone. But two years later, we heard about him again, and this time we jumped. I loved his playing and asked him if he would record. He was young, he was interested, it wasn't a very hard thing to arrange. But we wanted to make something that would be a little more glamorous than a single record.

So you did the entire "Well Tempered Clavier." Do you remember how long it took?

We did it in 12 weeks.

You were marketing your records through Book of the Month Club at the time. Could that kind of an outfit sell enough records by a young unknown to make such a venture worthwhile?

They had trouble [with the selection]not a lot of trouble, but they didn't make a lot of money on it. Whether that was because the artist was young, I don't know. I think it was just the repertoire; "The Well Tempered Clavier" simply doesn't have that big a market.

We did it pretty cheaply. We didn't cut any corners, but we were efficient. Even at that, we were using half-inch, 30-ips tape.

Connoisseur Society used that technique from the outset. How did that come about?

I wanted to do the best recordings possible. One of the major problems in those days was noise. If it wasn't record noise, it was tape hiss. So I asked around. I'm not an engineer, but I respect engineers and have a sense of those people who are talented, so I asked. And I got in touch with a few very bright people, one of whom was the son of Béla Bartók--Peter Bartók, who was then already a well-known audio engineer, a very nice man and very smart. He recommended using wide-track tape at 30 ips. There were some people recording half-inch three track, so the half-inch tape was around, but they were generally doing it at 15 ips. The result was definitely quieter -- 7 to 8 dB quieter -- though it wasn't the 15-dB improvement I thought it might be. But it sounded low.

Because the modulation noise-the hiss-had a different characteristic, it was smoother. Overall, the tape sounded really lovely.

You were cutting 12-inch discs at 45 rpm as well, weren't you?

We decided to try cutting the records at 45 rpm to get better fidelity on the discs. It was a wonderful idea technically but a bad move commercially.

Because the discs lacked playing time?

I don't think that was the problem. People were confused by it. You know, it's as simple as turning the speed switch, but nobody thought about doing that for a 12-inch record. They didn't want to bother.

Did you make parallel 33s at the beginning?

Not at the beginning, but eventually we did. We also had mono, so we had three configurations: Mono 33, stereo 33, and stereo 45. It was expensive, but we didn't want to give up the 45s.

However, when Book of the Month Club was involved with us-they went along with us and issued 45s as well--we saw [that 45s accounted for] only about 8% of the sales. I was being pushed by a lot of friends in the business to give up the 45s, so I did. For 8% it just didn't seem worth it.

How many 12-inch 45s did you make in all?

I don't remember the exact number, but quite a few--maybe 30.

When did you make the shift from records to cassettes?

We decided to go into the tape business in 1978. There was a severe downturn in the record business, and we got hit, as did other people. Although a lot of records were sold, it was all Saturday Night Fever one year and Elvis Presley the other. The general catalogs were suffering, and all we had was general catalog. With my brother, I formed a new company called In Sync Laboratories, and licensed, really from myself, the Connoisseur catalog.

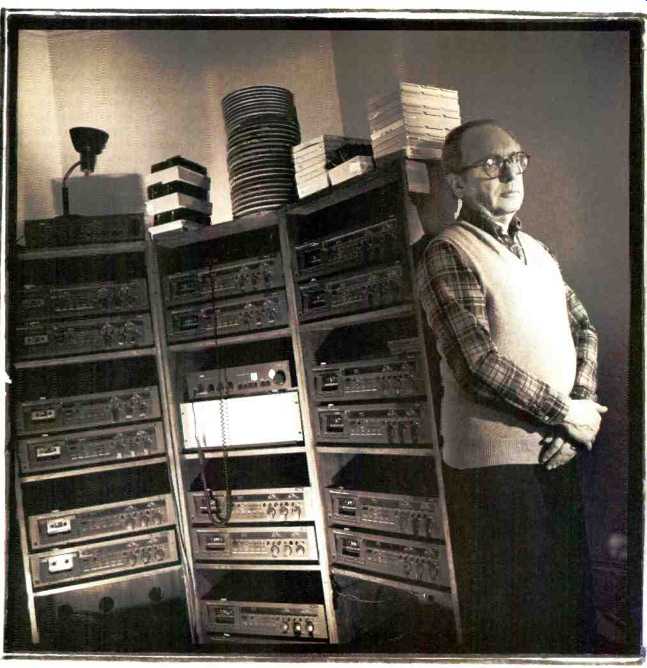

above: Cassettes.

Now you've gone to CDs. How many do you have out?

We have about 130 cassettes, and 20 items were out on Compact Disc.

We're not really in CD ourselves. Those 20 items we licensed to Nippon Phonogram, the Japanese division of Philips, which manufactures and sells them in Japan. We once imported them for sale in this country, but no longer do.

Let's talk a bit about your duplicating process.

We decided to go into real-time cassettes because it seemed to be the very best way to make them. It also gave us double control of the quality. We tried high-speed duplicating and got some very good results, but there was no way we could match even what could be done with a home recorder.

We checked out a bunch of cassette decks and narrowed it down to two or three. The one we finally chose, the Nakamichi 582, gave us as close a match to the master as we had ever heard. The 582s are still being used. They're still flat out to 20,000 Hz. One of the things that attracted us was that you could align each deck externally--from the front panel, like you would on a professional tape recorder-for every piece of tape you put into it. Every tape that comes off those machines has been individually aligned.

What are your feelings about the new DAT format?

I think it's an exciting prospect. I'm more interested in it than the major companies are, because I have more to gain. I'd like to duplicate DAT cassettes. As soon as the decks are around, I'll definitely get into it.

During the last few years you've put out some interesting historical material that underwent sonic restoration. Just what kind of processing was involved?

What you primarily need for historical restorations, I suppose, are clean recordings. It's hard to find masters, so you generally start with a shellac disc.

You play it back with what you hope is the appropriate playback curve with a 78 stylus, one of perhaps many different sizes and shapes [you've tried in order] to see which is the quietest and cleanest in terms of distortion. Using the correct stylus is part of the restoration. Reducing noise can be done in dozens of different ways. The way we did it was with notch filters, so you take as little of the musical content out as possible.

What frequencies do you filter out?

It depends. You have to do it by ear. It can be anywhere from, say, 5,000 to 9.000 Hz. You may also want to filter out noise from the 78 cutting devices, which would be down low.

Have you come to the conclusion--as so many others have--that there's more music on those 78s than initially met the ear?

Yes, I, have observed that, and frankly I came to that knowledge late. I wasn't aware how much there was on them.

Your most recent discovery was some unreleased concert material of the late cellist Emanuel Feuermann. That was quite by accident, wasn't it?

Yes. I was just prowling around the [ Manhattan] neighborhood near where live, and I went with a friend up to a cafe where jazz musicians play. I was introduced to the woman in charge of hiring these jazz people as somebody in the classical record business. She said, "My father was a classical musician." Her father was Emanuel Feuermann. I got very excited, and I said, "Is there anything that has not been released by your father that could be released or that you would like released?" And she led me to the acetates at Lincoln Center, recordings of two of her father's concerts dating from 1940 and 1941. It was just that simple and that much of a coincidence. Right here in the neighborhood. I didn't even know Feuermann had a daughter, or whether any of his family was alive.

What shape were the acetates in?

Very, very good, except for one of them--the Bloch "Schelomo.” Someone had done a really bad number on it. It had been gouged, scratched; it was virtually unplayable. We put coins on top of the arm and salvaged all but about four and a half minutes of it. The rest we had to take from an earlier taping that was done by the [ Lincoln Center] library at half speed with very, very heavy splicing. But we got it all.

These acetates that had found their way into the LincolnCenter library--how did they happen to be made in the first place? Was it normal practice to record concerts in those days?

A lot of concerts were recorded. Feuermann was playing with the National Orchestral Association at the time these concerts took place--they were at Carnegie Hall. Carnegie had a house recording setup. It didn't belong to Carnegie Hall, but they had agreed to let a company known as the Carnegie Hall Recording Corporation do recording inside the house.

Were these things made for archival purposes?

Strictly that, yeah.

Do you know what the setup was? Did they just put a mike in front of the soloist?

It sounds like they did that, but it's hard to know. They were doing mono recordings and probably didn't want to muck up the stage with lots of mikes. It doesn't sound like multi-miking.

Are you doing any original recordings now?

I've been doing original recordings, but at such a slowed-down rate it amounts to only one or two a year. We used to do five to eight a year. I'm trying to get back to doing more.

What kind of sessions do you hope to be producing?

Things like I did in the past. More piano recordings, more violin, more string quartets. I never did much, really, with string quartets, but I love them.

You've recorded several artists from behind the iron curtain. Did political problems ever enter into your relationships with them?

Yes, there was some difficulty with the violinist Wanda Wilkomirska. The first recording we scheduled with her was late in 1968. She was supposed to be here sometime in September, and about two or three weeks before that, the Russians moved into Czechoslovakia. Well, the visa we had for her was suddenly cancelled because Poland was part of the Soviet bloc. I was despairing. Here we had this recording set up, I had hired people, I had money laid out-and I wanted to make the recording. So I called Immigration, and they said, "Well, we're very sorry, but this comes from upstairs. No Soviet or Soviet bloc artists are going to be permitted in." So I spoke to my lawyer, and he said. "Why don't you go down there and talk to them personally? Tell them you're a small American businessman and that by depriving you of her work they're hurting an American small business." I went down to the immigration office and pleaded that I needed this artist for my business.

They listened, and they asked-very gruffly, I thought--"How many days is this recording supposed to take?" I said, "We're supposed to do it in four evenings." They said, "Just a moment," and then they came back.

"Okay. She can come for five days." So she did. We knocked it out, and she went right back home. Interesting, the reason they permitted it.

Interesting, too, that they cancelled her visa in the first place. The Russians are at war with the Czechs so a Polish artist suffers.

Well, there's a lot that you and I don't know. Now, Wanda was not a political person, and I knew nothing about her except that she was a violinist from Poland. Her husband was a journalist.

Later she and her husband divorced, and I found out a little bit more about him. While it has nothing to do with the recording sessions, it's conceivable our government knew. Her husband's name was Rakovski. He's the Vice Premier of Poland now.

And he had been a journalist?

Look, we have actors that become President. It has nothing to do with that. Who is to know who's political? Wilkomirska was married to a top Polish politician-or at least someone who had the potential. Whether our government was aware of that I have no way of knowing. She became a dissident and left Poland permanently, but he husband was a very important man.

In that case it was our government that intervened. Have there been instances where their governments have caused problems for you or your artists?

There was quite a problem with the Russian pianist Oxana Yablonskaya. I was looking for new artists, I think i was in the late '70s. My former wife said there was a Russian pianist who had won the Rio de Janeiro competition in 1965, a joint first-prize winner, who had a beautiful tone. There was no way of hearing her, but I figured may be this Yablonskaya had some records in the Soviet Union. So we asked representatives of the state-run record company, Melodiya, who were here in the United States, if we could get any information. Did she record, and so on? "No, there are no recordings. In fact, we don't know of any pianist named Yablonskaya." That was a bit puzzling. After all, she was a first-prize winner; they had to know her. Well, we asked a manager in New York who was working with other Soviet pianists to check it out on his next trip and see if he could find out where she lived, who she was. He came back and said he had checked, but there really was nobody by that name; we must have the name wrong. So we dropped it.

Well, about a year later, in a New York magazine listing of concerts for the week, there was a lady's face--Yablonskaya at Carnegie Hall. We didn't have the name wrong; we had it absolutely right. She was Jewish. She had applied for an exit visa, and they had made her a non-person. You know, you read about that and you don't believe it. Well, this really happened. They said she didn't exist. But she was there.

They let her out to perform here?

No. She had by this time gotten out. She had asked for a visa two years before we had asked about her, and they had taken her job away. She had to sell her piano for money to live. She was just waiting for an opening to get out of the country with her son. And when she finally got out, friends helped her get a manager in New York, and the manager presented her at Carnegie Hall. She had records, by the way. Melodiya had made records of her. We got them later.

As a record producer, your fortunes depend to a large extent on critics. If they pan one of your performers, either in concert or on disc or tape, you can be hurt. Just how good are today's music critics?

I think most reviewers are pretty good, but I do have a bone to pick. Reviewers very often review their best friends. I don't think that's right. The best friend may be one of the finest artists around, but I think the reviewer should be like a judge and disqualify himself or herself. I don't know why that's not done.

It's always struck me that the career path of a young classical musician is incredibly complicated. A writer, for example, needs a typewriter, ribbons, and paper, none of which costs much. But a violinist may have to rent a recital hall and pay musicians to accompany him or her. All this, of course, to get reviewed and attract the attention of managers.

Foundations and the government should provide for young performers. A young performer, let's say a very good talent, plays in New York-they all want to play in New York, they all need the imprimatur of Carnegie Hall, The New York Times, and so on. And let's say he or she plays wonderfully.

Now let's say, case one, the reviewers don't like this kind of playing--and we're assuming a good performance.

The artist has taken his or her money, laid it out, played, and it comes to nothing because the reviews are useless, they're bad. Or let's say the artist comes and is nervous-it happens-or isn't feeling well and doesn't play as well as he or she is able. The reviewers, justifiably now, give bad reviews.

Same result. Others can't afford to play, though they may be talented and worthwhile artists. Or they play wonderfully, but only one reviewer shows up because it's a crowded schedule.

And the reviewer that day had a fight with his or her spouse, or was sick, and had a poor seat at the concert and panned it. Nothing to do with real feelings or the performance, but the same result: The artist is not helped. And Carnegie is not cheap, publicity is not cheap. You're talking about many thousands of dollars.

If, on the other hand, you make a recording of a young performer with talent, his has a much greater chance of helping him or her. If the artist plays badly, you can cancel the recording and do it another day. If the artist makes mistakes because of nervousness, you can edit the mistakes out.

You can give the best possible picture of a performance. Then you don't send review copies just to the three New York dailies, but to 75 reviewers around the country. Now you have the possibility-through the recording medium-of 75 reviews, and maybe 20 will actually be written. Out of the 20, maybe five reviewers will murder the artist and 15 will love him or her. That's useful for a career. Then you take the recording and send it out to the radio stations, and maybe 100 classical stations will program it once, and maybe 10 or 20 will program it 10 times, and a public begins to hear that artist. So the recording medium offers young performers a great advantage, something that supplements a Carnegie Hall appearance and in some cases can replace it. The recording industry can be a great help to the live music industry if it gives young performers of merit an opportunity to be heard. I plan to do recordings of more young artists because I think it's important that young talent be nurtured, and this is a way of doing it. You give them a showcase, a chance to be heard by many, many people. It must be heartbreaking to play a concert in a major city and not have it work for you.

(adapted from Audio magazine, Jul. 1988)

Also see:

Audio Interview, The --Tom Jung--The Digital Music-Man (Aug. 1988)

= = = =