by DAVID LANDER

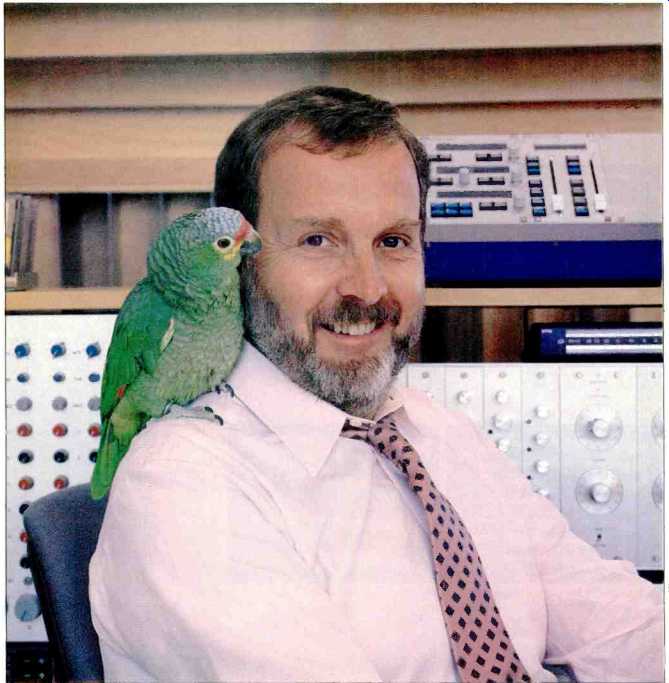

Record producers generally feel that they are in the business of marketing talent. While Tom Jung (the "J" is pronounced. as in "jazz”) is no exception, the founder and president of Digital Music Products, believes in delivering a lot of technology with his music.

The entire dmp catalog, which has grown to nearly two dozen titles, since the first discs were pressed in 1983, was recorded on a Mitsubishi X-80 digital machine. Jung’s newest projects also benefits from his love affair with class-A electronics and such exotica as hand-built ribbon microphones, high-performance cables, and the Cello Audio Palette. The fact that dmp has never produced an LP is also telling, although early on, its proprietor did make one concession to the marketplace by offering real-lime analog cassettes.

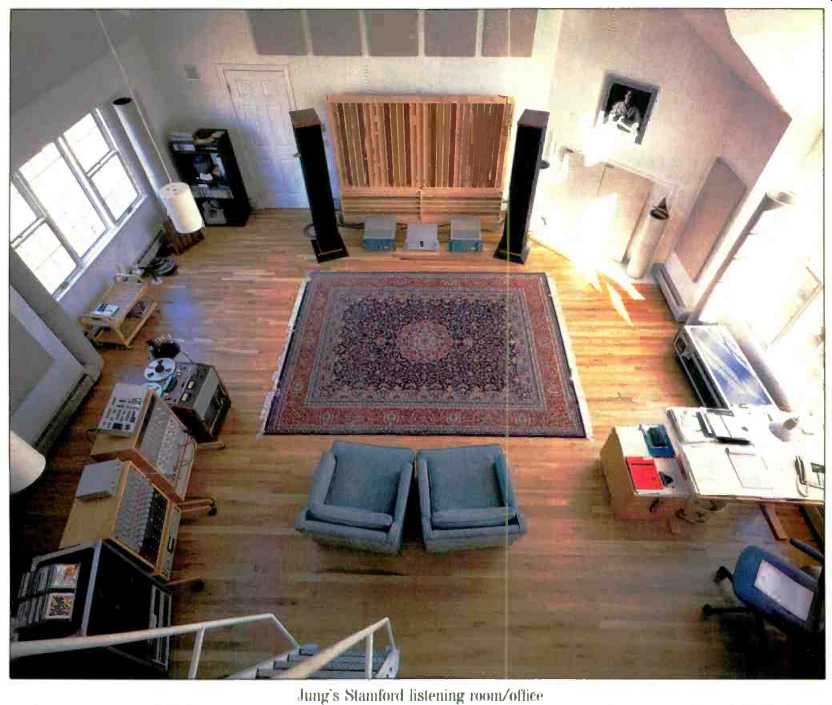

Jung's company is now based in a chic condominium complex which stands by Long Island Sound in Stamford, Connecticut. He hails from Minnesota, where he got his start in the record industry as a disc cutter 25 years ago. From that spot, Jung moved to field recording and then studio work. During those years, he recorded everything from polka bands to 300-voice choirs--and even a couple of hit rock n' roll songs.

In 1969, Jung and a producer friend got together with outside investors and built a state-of-the-art recording, studio called Sound 80. (Its then-futuristic name, Jung confesses, was dreamed up by the ad whiz, credited with naming Hormel's Cure 81 ham while drinking Val 69 scotch.) By 1979, the business had grown substantially, and Jung found himself in management. Hoping to produce his own records, he migrated east and soon became a busy freelancer in the buzzing hive of New York studios.

While free-lancing, he made many professional connections and continued to formulate his dream.

With the first dmp recording, mastered in 1982 and transferred to CD in 1983, that dream was realized.

--D.L.

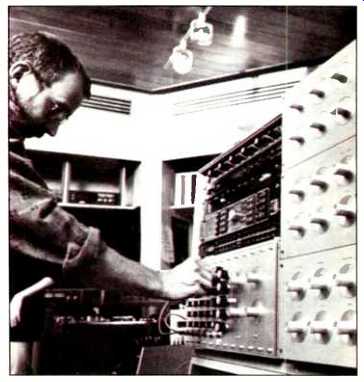

You were involved with the first recordings made on 3M's experimental digital recorder back in the early '70s. How did that come about?

We were doing a direct-to-disc project, so it was a perfect opportunity. At that time, most sessions were multi-track--I think our studio was 16-track--but I always felt that certain aspects of audio quality were actually going backwards as the tracks increased. So I had a keen interest in recording live to 2-track.

And the 3M prototype was a 2-track machine. What was it like?

It was a little R2D2-looking machine.

They nicknamed it Herbie. It had an instrumentation transport, used 1-inch instrumentation tape, and went at 45 inches per second. You couldn't cut the tape with a razor blade; you couldn't do anything with the unit but record and play. As long as we were doing a direct-to-disc project, where we were going for a whole side, it didn't matter that editing wasn't available. Even sequencing, cutting in dead air between movements or between tracks, was a problem. There would more than likely be a click at the splice. The machine was unbelievably unreliable. When you made a recording and went to play it back, you just kept your fingers crossed that something was going to be there. But when the 3M prototype worked, it sounded great.

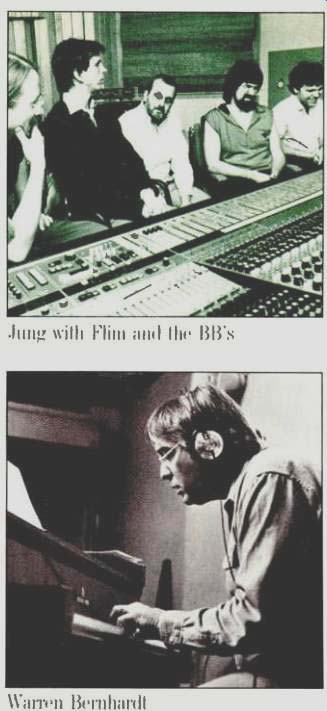

You did a recording of Flim and the BB's, who have since become key dmp artists, on that machine. How did you discover the group?

At the time, Flim and the BB's was kind of a studio band. They were doing the lion's share of the recording work in Minneapolis, working for various producers and artists. We were all friends, and it was an opportunity to do something on the jazz side, which is where my roots are.

That's right, you were a bass player. When did you move east?

In 1979, Sound 80 was 10 years old and had grown to about 28 people, and I was more of a management figurehead than a creative person. Something clicked around the time we tried the digital recorder in the studio with Flim and the BB's, and I really felt that digital was going to be the future of recording music for consumers. At that time, my wife and I started talking about what fun it would he to have a small, high-quality jazz label concentrating on the kinds of things we wanted to do. We also started looking around the country for the best place to do this and, obviously, zeroed in on New York, which is the jazz capital of the world. But 1979 was not a good time to fulfill our dreams because there was a crunch in the record business.

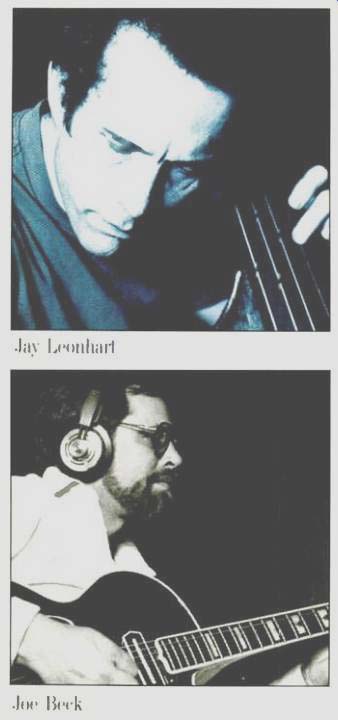

On the other hand, I felt we really had to make the move. I figured, well, with my engineering and production background, I could find work on a freelance basis, and I did. It was also a great opportunity to meet a lot of players and, as it turned out, that worked beautifully. I met people like Warren Bernhardt, Joe Beck, and Gerry Niewood in the studio, and I began a casual dialog about starting a label and asked if they would be interested.

The response was overwhelming. So in '82, we started doing some recording.

You did an early dmp recording with Flim and the BB's and then three more recordings. Was that your first album on the label? And why are they the dominant dmp group?

Recording with those guys was always real comfortable. From the first album, they zeroed in on the wide dynamic range, the fact that the noise floor was 30-some dB lower than on the typical analog recording. They really used that extra range in terms of the music they composed and played. I've always been in favor of trying to maintain natural dynamics, and these guys thought, wow, with the noise floor down in the 80s to -90s, there's real dynamic potential for some new music. And they came up with it. It was a real natural thing, musically and technically, for us to work together. Actually, the first project we did was a solo piano recording with Billy Barber. The second project was Flim and the BB's.

And what came next?

We did Warren Bernhardt's Trio '83 album, Joe Beck's be-bop record, and then Jay Leonhart. Those five albums were complete-recorded, edited, and in the can-in '82. It took until the end of '83 before anybody would say, "Yeah, we'll take your master tape and make you a batch of CDs."

Getting CDs pressed back then was an enormous problem, wasn't it?

I had verbal commitments from quite a few plants, but we were too small and unknown. The major labels got the press time.

When you finally got your first discs, how did you go about distributing them?

Our first CDs were probably among a couple of hundred available in the world. When we first got them, I went to MIDEM [a record industry conference] in Cannes, France to look at the worldwide market. Of course, there wasn't any at that time, and that was a bit of a rude awakening. I was probably the only person there walking around with CDs in my bag. When I got back, we really felt that, because of the kind of music and the dynamics, a ripe market for us might be the hi-fi market. So we got to know some manufacturers, went to Consumer Electronics Shows, and basically handed out software. Everyone was very receptive.

Even then, you refused to make LPs. Did people think you were mad?

They did. For a period of time, we did make a real-time duplicated cassette. I didn't want to get into LPs because I felt there weren't any good, high-quality LPs made on this continent. I figured, why should we start a new label with something that was going to be short-lived?

Are you still manufacturing analog cassettes?

No, but we recently started to make digital cassettes.

You've been quoted as saying that these are sonically superior to CDs.

Our DATs are better than our CDs.

There are two reasons for this, and I'm not sure which has the most significance. We record everything live to 2 -track on the Mitsubishi X-80 digital recorder at 48 kHz, and we do a digital conversion to 44.1 kHz for the Compact Disc. So it's a lower sampling frequency, and a conversion takes place. Even though it's a number-crunching digital conversion, there are some sonic differences between it and the master tape. When we make a DAT, we go digital to digital, from X-80 to DAT. There's no conversion involved, and we maintain the higher sampling frequency. The combination of those two things yields better results. I maintain that a higher sampling frequency is better, especially when you're dealing with nuances like the color of the reverberation in a hall or extreme high-frequency detail on percussion and piano harmonics.

The X-80 is only one part of the dmp equipment equation. In terms of the complement of hardware you employ, you're on the leading edge of recording technology. How do you evaluate this stuff? Is it strictly by ear?

About three years ago, we bought what I consider to be a very sophisticated piece of test equipment. It's a Hamburg Steinway grand piano. It provides a reference. You can put your head in that piano and then listen to the results of whatever, however you recorded it, out of a very high-end playback system, and you can really hear the differences. It helped me find weaknesses in the recording chain--the microphones, power supplies, cables, mike preamps, line amps, mix amps, and analog-to-digital conversion techniques in various digital recorders. These things show up quite readily on the piano. I'm sure many of the sonic differences we hear aren't being measured.

The harmonics of a piano are incredibly complex... .

That's right. Especially the high-frequency harmonics. And the wavefronts that can be established with a strong player are severe. We've found that some of the op-amps used in conventional equipment really can't accurately track these waveforms.

So you turned to unconventional equipment?

I was thoroughly discouraged with the sound of so-called "professional" equipment-the consoles and mixers available to the trade. By the time we started dmp, using op-amps--and not even using them to their full potential--was commonplace in professional audio. With multi-track recording, console design was so feature-oriented that the signal path took a back seat.

That's when I started making a departure from conventional recording equipment. I was looking for something that would give me the flexibility to do contemporary recording, but with the purity of passive or virtually no electronics.

You make a point of using Class-A electronics. Why?

I think I looked at and listened to everything, and my background is technical enough to know what happens in Class-A biasing and circuitry. It really makes sense. This amplifier's cooking all the time; it doesn't wait for the signal to come through and then demand that the power supply deliver something it might not be able to. This thing is turned on all the time, so the music doesn't change its characteristics. To my ears, it has the most natural electronics I've ever come across. I started to realize this when we got the Hamburg Steinway. It was real apparent that piano transients and wavefronts were realized through Class-A electronics, whereas they were just squeezed through in more conventional op-amp designs. The 5534 op-amp is used extensively in equipment these days, particularly in pro gear. And as I eliminated 5534s from the signal path, the sound kept getting better.

Tell us about your choice in microphones.

I discovered early on that a lot of the condenser microphones used in making analog recordings were not well suited for digital. With analog, things happen, like high-frequency saturation, so what you have to do in the recording is pre-emphasize what you want to retrieve. So the industry started making microphones that were purposely hyped on the high end just to maintain sizzle from instruments. Now, a lot of the criticisms of early digital recording can be related to just taking these old techniques and simply replacing the analog recorder with a digital recorder. All of the high-frequency bumps came back overly bright and harsh-all the things that digital got blamed for. Well, early in the game, I said let's reevaluate the microphones and start at the beginning. I sort of rediscovered ribbon mikes, which I had used for years with brass and certain instruments. I found they had a much smoother high end; a lot of the characteristic brightness of condensers was gone.

But are there attendant problems with ribbon microphones?

The problem is that their output is extremely low. Working in big rooms, as I do, with long microphone cable lines, I was losing a lot of high-frequency information in the cable. So I had some pre-preamplifiers built for me, again Class A, discrete. In the studio, I put these as close to the performer, as close to the microphone, as I can, and I use the shortest possible cable (in many cases, only 3 meters). So I get my gain-say, 50 or 60 dB close to the microphone, which helps preserve some of the detail this poor little ribbon mike is trying to drive down the cable.

By bringing the signal up to or near line level, and by balancing it at that point with a good line amplifier, I can drive several hundred feet of cable with virtually no losses. I feed the signal into my rig, which is virtually a line-level mixer. I have the ability to grab up to 30 dB of gain in my mixer, but basically I bring everything in very close to line and then mix at line level. The advantage is that more harmonic accuracy is maintained.

You also use some pretty exotic cables. Do you really find the nature of the cable makes that much difference?

Everything makes a little difference. I don't think one thing makes all the difference in the world, but I've found that different cables sound different. Monster Cable sounds different than Cello cable, which sounds different than the new, experimental, linear-crystal cable from Japan, which I'm using right now.

Basically, it's an entire copper crystal stretched out to about a meter in length. I end up using different cables for different instruments, depending on the response characteristics.

You try to use these characteristics to your advantage?

Absolutely. I like to think of myself as a purist, but I don't throw out the idea that equalization is necessary sometimes to get the right tonal balance, particularly in the area of recording drums. And I've yet to record a piano that doesn't require some equalization.

I don't like to use a lot of it, though. I try to use as little as possible because it has its own coloration. On the other hand, to get the tonal balance and the spectrum I like requires a little shaping.

I do this with the cable if I can, but if I can't, I insert an equalizer.

You prefer the Cello Audio Palette. Do you do all your equalization on that?

Not all of it, but as much as I can. At 10 grand a pop, I don't have a lot of them standing around. On special projects, [Cello founder] Mark Levinson has been nice enough to loan me a few.

We've used three or four of them on several projects. I think the Cellos provide the most musical equalization I've ever heard. In typical professional equalization applications, you have a million frequencies, and you're able to equalize little, narrow bands. But those little, narrow bands, or high-Q equalization curves, also produce more severe phase shift, which really starts to mess with harmonic integrity. That's why I like Cello's broad-Q, wider, spectrum-shaping approach to equalization.

Isn't this the approach Mark Levinson and his designer, Dick Burwen, took with this piece of equipment?

Yes. I had some professional equalizers modified to get broader curves than Cello has, and these professional equalizers sounded better for it. I've just acquired a digital equalizer, and it's part of the DAT mastering stage.

It's basically a 24-bit internal equalizer that does some serious number-crunching and mathematics. It's a six -band equalizer. I've had the company in Germany that built it, Harmonia Mundi [not to be confused with the French record company of the same name], design some special curves, which are software changes, to resemble the Audio Palette. Now I have those kinds of curves available to me digitally. So once I get something converted to digital, once I do my original recording, I can still get another crack at doing some spectrum shaping in the mastering process in the digital domain. Basically, the Harmonia Mundi allows me to make level and balance changes--along with equalization changes--while going from one digital format to another. I do the original recording on the X-80, razor-blade edit the master, then transfer it to DAT-all in the digital domain, without going through any converters. Then I build my CD master on DAT. The new Bob Mintzer record was the first project mastered to DAT. The disc plant actually took a DAT and converted it to 44.1 kHz for transfer to Compact Disc. Now, through all these conversions, the signal never comes back to the analog world, it just stays numbers. So it's an endless number-crunching deal until someone actually puts a disc in a player and brings it back to music.

If you think enough of the DAT format to use it as a master tape, do you also see it as the dominant format of the 1990s? Is it going to replace the Compact Disc?

I don't think so. I see DAT and CD coexisting, as LPs and cassettes did for years. They're two different mediums, and I think CDs have certain advantages that DATs will never have and can never have. DAT is a magnetic medium-it's subject to wear; it doesn't have the track access that CD does; it doesn't have the archival quality. It does have one advantage, though, and that is a higher sampling frequency. The industry itself, I think, will probably stay with the lower sampling frequency because most digital masters are made at 44.1 kHz. There's really nothing to be gained by going from 44.1 up to 48. If the original recording is 44.1, you're not going to capture any more high-frequency detail by going to 48. For a little company like us, trying to carve a niche in high -quality recordings, it makes digital all that much more viable for the audiophiles--the people who are really trying to hang on to the LP. Higher sampling frequency and the lack of conversion actually get you closer to the real thing, and that's what audiophiles are looking for. Ideally, they'd love to see 96-kHz sampling, but it really isn't possible to do that economically at this time.

How close are we to that elusive "real thing," to hearing an exact reproduction of your Hamburg Steinway or of a 9-foot Baldwin grand?

We're getting closer, but there's a long way to go. I think it's remarkable, doing it the way we do, that we get this close.

You've developed a unique way of recording big bands. Could you explain that process and tell us how it evolved?

I've always been a big band fan. When I was a kid, if Stan Kenton or one of the big bands came through Minnesota or North Dakota or South Dakota on a tour, I'd talk somebody into driving me there. And I'd stand right in front of the stage to get the thrill and sheer energy of this 18- or 19-piece band blowing right in my face. I was forever frustrated with the way records sounded, and, as I got better and better equipment, I found that the big band sound just wasn't on the disc.

What, specifically, wasn't there?

Harmonic detail, I think. You heard this glob of sound that resembled a big band, but it really didn't have the nuances of a live performance. And, of course, it had things that weren't in the live performance, such as distortions, harshness, microphones and mike preamps that were overloading, things like that. This always gnawed at me.

And having recorded many big bands myself, I felt that the sound I was getting was as wrong as on any record I'd ever heard. Then I had the idea of getting as pure a signal path as possible from a single-point source pickup, meaning one microphone. By setting up the band around this one microphone, the balance would be achieved acoustically rather than electronically, or artificially, if you will. I used a bidirectional ribbon stereo microphone and then set up the band in two semicircles. We were really dealing with two stereo images-reeds on one side of the mike, brass on the other. One stereo image was the reeds; the other was the brass. It was an X-Y configuration, of course, so the images folded together in a left-right situation. Thirteen horns were recorded with one microphone, and balance changes and corrections were achieved through old-fashioned placement-slide back 3 inches, move up 2 inches. When you soloed, you stood up and walked to the mike, up to a mark on the floor. And that's how we achieved balance. I think we came much closer to the live band sound-even though we were taking this incredibly complex thing, harmonically, and trying to force it out of paper cones.

You prefer recording in large rooms. Why is that?

In a big room, the early reflections are displaced enough in time where I think the direct sound from the instruments really gets a chance to develop. The sound doesn't get colored by a reflection that's too early.

You've also worked on movies--The Cotton Club, Annie, Dressed to Kill. How much room for improvement is there in movie sound?

I think there's a lot that can be done in movies, and I'm amazed that more hasn't been. With videotape and some of the competition that movies have right now, it seems that the theater, other than providing a place to go, could offer a lot more visual and audio quality. Certainly, with digital sound, there are endless ways to improve soundtracks. But it's a very involved process when you think about it, because everything--from dialog to sound effects to music--would have to be recorded digitally.

What improvements do you feel are needed in digital recording?

I think there's a great deal of improvement to be made at this very critical point of converting from analog to digital. Converting something as delicate as music and harmonics, and converting all of the nuances to zeros and ones accurately, is a big, big, important step. That's an area that needs more attention. I also think a greater degree of accuracy can be achieved through more accurate conversions; the analog electronics surrounding the converters and filters have been grossly overlooked. Again, we go to all this trouble to stay Class A up until the time we feed the signal into a digital recorder. In most digital recorders, you go through that same 50-cent 5534 op-amp before you even get to the analog-to-digital converter. These areas really need to be cleaned up.

You said early in this interview that you set out to start a "small, very high-quality jazz label." Yet you're often seen as an audiophile specialty label. How do you feel about that?

I almost resent that a little bit because think the most important part of what we're doing is the music; the sound is really secondary. If I can bring realism to the music in a recording, I've done my job. But one of the things I'm trying to pay more attention to is finding really great tunes-those killer numbers that could be standards some day. The rest is all a means to an end. The music is what's really important.

Let's talk about that. The fact is, dmp has a distinct musical signature in that you've put together a stable that includes a lot of seasoned studio musicians, largely New York-based. Clearly, these people move in the same circle because they keep showing up on one another's albums.

Some of the finest musicians in the world live in New York City. It's a real kick for me to assemble a roomful of really great players. To have such a great stable of musicians available to choose from and to work with is a great pleasure and an honor.

They are, in fact, often musicians who've played with some of the top recording stars. Outside the studio world, though, they're generally unknown. Along with a hell of a lot of virtuosity, don't they bring some marketing problems with them?

Well, it's definitely difficult, and it's very challenging. But it's also very rewarding when you can make something happen. All we're trying to do is make as good a record as we possibly can--both musically and technically--and then expose it. We've recently started paying a lot of attention to radio, and with the Thom Rotella Band, we've had some terrific success, even though it's hard to label their music.

In fact, much of the music you record is a little like something or a lot like something else. Your artists perpetually cross stylistic boundaries and tend to elude characterization. Is this because, in their day-to-day studio work, they come in contact with so many styles of music--because they're just so versatile?

Rather than do something that's been done before, the artists we work with--like us--want to do something different, something that hasn't been done before. A group like Flim and the BB's is a good example. I don't think there's anybody that really sounds like Flim and the BB's. The band comes off as four guys having a real good time making music they like to play. And I think our audience is attracted to what we're trying to do. It's different, it's fresh, and it's fun.

There's always more than one producer credited on your albums. Not only do you credit one or more of the performers as producers, but you list your own name last. Is this simply politeness, or do your artists have a lot to say about what their albums contain?

They do. It's definitely a cooperative effort in terms of choosing material. I see us as equals. It's important to me that the artists feel good about the music they're recording. Hopefully, we can do that and accomplish some accessibility at the same time.

You've expressed a distinct preference for acoustic instruments over those that are electronic.

I'm attracted to that real human being playing that acoustic instrument. The nice thing about recording musicians and acoustic instruments, rather than computers and synthesizers, is that more of the artist's personality-or soul, if you will-can come out.

Yet there are electric guitars and drum machines and synthesizers on your recordings.

Absolutely. I try to look at the synthesizer as another instrument, not as something replacing instruments. I think synthesizers are overused today, and maybe I overreact a little in trying to downplay them. But I think they do have their place. The synthesizer is an instrument that's no more or less important than any other. But I'm bothered when it starts replacing drums and pianos and many things that should be acoustic.

A few minutes ago, you used the word "accessibility." That seems to me a critical aspect of the dmp musical signature. Yet your Pugh-Taylor album, which showcases a bass trombone, a tenor trombone, and some pretty radical compositions, directly contradicts this philosophy.

I worked with and listened to Dave Taylor and Jim Pugh in the studio, and I loved the way they sound. When we started talking about a project, we addressed the issue of the risks we were willing to take. And in some of the compositions that were written for them, we took great risks, broke a lot of rules, crossed a lot of boundaries. We also learned a lot, and I don't regret doing the project. I believe a lot of people, particularly in the foreign markets, would like to see us do more of that kind of recording. We aren't apt to do it, because the business itself is much more competitive today. Without trying to be commercial, I do get a great sense of accomplishment by recording good music that can reach a lot of people.

There's a Jewish legend in which a rabbi is asked to define Judaism while standing on one leg. If you were asked to recite the dmp philosophy while standing on a single leg, how would you respond?

The direction of the label is definitely jazz-oriented. I hate to say jazz, but I keep coming back to the term "jazz -oriented," because I think the common denominator for these recordings is that all of them are improvisational--at least in part.

(adapted from Audio magazine, Aug. 1988)

Also see: Audio Interview, The: E. Alan Silver--The Connoisseurs’ Selection (July 1988)

= = = =