By JON & SALLY TYVEN

How does a pro set up his home studio? Want to add some of the studio effects to your home-brew tapes? Here are a few answers from Contributing Editor, Jon Tiven.

----------

"It's become a fairly common occurrence for recordings made entirely at home to be issued as records. In other cases, a basic track, cut at home, winds up as part of a record."

----------------------

Over 10 years ago, when TEAC introduced their Model 3340, a medium-priced, four-channel open-reel recorder, the private at-home studio became the focus of many new products. Today, only a short time elapses between the introduction of a special sonic effect box into the studio or pro market and the emergence of a near-relative effect box for the aspiring amateur. And this is for good reason, because four-channel recording gave basement studios, based on bouncing signals from one tape recorder to another, a new chance to approximate pro sound. In deed--; using the TEAC 3340 or one of its imitators, at-home studios have produced a number of hits, or at least portions of hits. No longer would generation after generation of sound quality be lost, since the 3340 made it possible to record several instruments at once without the usual Gordian knot of patch cords. In short, the overdub had come into the home.

Recently, with the advent of drum machine-based music, it's become a fairly common occurrence for recordings made entirely at home to be is sued as records. In many other cases, the basic track, after being transferred to a 24-track machine, is incorporated into the master tape and eventually into a disc. There is a reason beyond simple economics for this; the atmosphere allowed by such informal set-ups is far more conducive to creative performances than is the cold and stodgy ambience of most professional studios. The less-rigid home studio often captures music that isn't easily duplicated. For example, Bruce Springsteen's most recent album, Nebraska, was recorded on a home-style four track cassette machine; considering how many hours he is reputed to spend in studios, which go for $150 per 60-minute bite, the savings in production costs on Nebraska must have been phenomenal. It is possible to make great-sounding tapes at home; the technological gap is narrowing.

In my experience, most folks who have home studios aren't out to make records there or even do it for the money; it's simply a facility for enjoyment.

So in hopes of making the home studio proprietor better aware of what's avail able to him, without killing the ol' bank account, I've compiled a guide, loosely speaking, to the various types of home studio gear. Along the way, I'll name a few specific models, but these units aren't the only ones around; they're just good examples of the type.

Tape Decks

When TEAC's 3340 first emerged, it was perfect for your basic rock band, because the guys generally had the other half of what was needed-the mixing board-from their P-A system.

But many home recordists had to buy their own mixers-that is, until fairly recently when the manufacturers started to produce all-in-one machines.

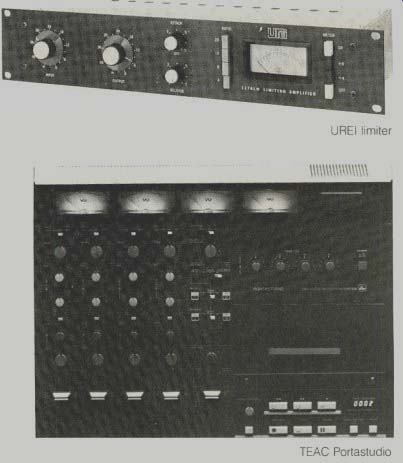

Two good examples are the TEAC Porta-studio and the Fostex Model 250, both four-track cassette decks that operate at 3 3/4 ips, have built-in noise reduction, and-most important-contain their own built-in mixers. The fact that they are cassette based eases the use of backwards recording and tape handling in general, and even better, the sound of these units is superb. To top it off, the controls are user-friendly, which gives the recorder-mixer marriage a tremendous shot in the arm.

Being able to control the EQ as well as handle outboard gear and four-channel bussing was almost as much of a boon to home recording as the introduction of the four-track recorder was. Add in such features as variable speed control, sliding faders, and zero-return functions, and these recorders become outright aids instead of obstacles that could block the creative experience.

---------------

"In my experience, most folks who have home studios

aren't out to make records there or even to do it for the money; they're

simply facilities for enjoyment."

------------

As far as choosing a deck for receiving the mixdown, the same general rules apply to your prospective machine as they would to any tape deck you'd consider. Ease of careful maintenance is even more crucial than be fore, however, and one should also choose a deck that runs at 15 ips to insure that the master tape accurately reflects the sound one has achieved on the four-track. Both Technics and TEAC have excellent decks for this purpose, but they're not the only manufacturers making quality reel-to-reel decks and there are many options in this category. Other brands to consider are Otari, Revox and Tandberg, though they may be more expensive.

Reverb and Delay

There is much confusion here as many people refer to both reverb and delay as "echo." There is, however, quite a difference between these functions, and each can be used to good effect in the home studio. To clarify, delay is a single, articulate recreation of a signal, added a certain few milli seconds later. It's often used for a thickening effect or used in tandem with harmonic modulation to achieve phasing, flanging or a chorus (dependent upon the length of delay). Reverb is the creation of many short delays which are added almost at once to make the signal appear as if it had been recorded in a certain size and shape of environment. It delivers what some call a larger sound or a room sound (natural reverb is often referred to as ambient sound). These effects can be achieved through various means- digital, analogue or (in the case of reverb) even the spring system, and each has its own characteristics.

The most common reverb unit is probably the spring system, found in many guitar amplifiers and recently improved upon greatly by audio manufacturers. Fostex has a unit which incorporates a short electronic delay with a spring reverb system, and it delivers an excellent sound, particularly for vocals. In a slightly higher price bracket, the Mic-Mix Master Room XL 121 is an exceptional unit that allows the user to equalize the reverb and also has a built-in preamplifier. If one wishes to really go all out, manufacturers have come up with digital delay/ reverb chambers. The Dynacord version has four different delay settings, four decays, and a digital delay built in as well. The unit is exceptional, but the price ($1500 approximately) will be prohibitive to some.

Where reverb was traditionally accomplished through the spring system, delay was accomplished through an auxiliary tape machine recording the signal on a tape loop and playing back the information milliseconds later. The invention of digital delay added flexibility and ease to this function, and the past five years has seen the price of home digital delay units dip well under $500. MXR's unit is a fine value for the money, as it includes easily operable modulation, phase inversion for the delay, and has an overall design which is nearly unbeatable. The Fostex reverb unit is also good and is designed to hook in to the Portastudio or 250 with great ease. The Dynacord DDL sounds good but isn't as flexible when it comes to choosing an exact number of milliseconds of delay. This particular effect is used to great advantage on most vocals that you hear on today's records, and is also quite useful for adding color to keyboards (in the shorter delay settings), guitars (in the chorus settings) or just about any musical instrument.

Compression and Limiting

The compressor/limiter is what some refer to as the invisible effect because if it's doing its job, you shouldn't really hear it. What it's designed to do is to even out the volume of a performance which otherwise would be too loud in places and too soft in others. The side effects of compression, if it's not done accurately, can make the background noise level jump around unpleasantly.

Similarly, a limiter will strangle a vocalist if it's used with too much enthusiasm. There should be enough signal to-noise in your system to handle most signal sources, but out in the real world there's hardly a vocal or acoustic guitar performance recorded without the aid of a compressor. Indeed, most re cords are put though limiters as a standard part of the mastering process, to prevent overcutting. At its worst, an overcut record will throw the stylus out of the groove.

The Fostex compressor is a reason ably priced unit that does the trick, in stereo yet, and has a built-in noise gate which is only effective when there is the most extreme amount of extraneous noise, as it isn't particularly sensitive. Another firm in this area is dbx, which may be more familiar for their noise-reduction system. However, they also have a compressor which some term the "One-Knob Wonder" because there aren't very many controls on it; even a pilot light is missing. Whatever your feelings about lots of bells and whistles, the sound of this unit is quite amazing. The UREI limiter is considered by many to be the industry standard, and although it's pretty expensive when purchased new, it is possible to purchase a used one for about $300. This unit retains its value pretty well if it has been reasonably maintained.

Noise Gates

The original purpose of the noise gate was to eliminate unwanted signals by sensing when the wanted signal was coming through and refusing to allow hum and buzzing while the wanted instrument/vocal was not active. As the word "gate" implies, it acts like a door, shutting off the track when intruders threaten the integrity of the recording.

Experimentation has proven gates to be effective in tandem with reverb units to control decay time, and they are also highly useful in general recording.

They can be used to key one signal to the rhythm of another track-for in stance, if you want to sound a key board note in time to the track, you can play a sustained passage on the key board and have the drums key it through the gate.

The Omni Craft GT4 is probably the best unit of this type available in the low price range, as it is quite flexible and responds with great accuracy and precision. The one problem is that it doesn't have an on/off switch or indicator; but this is a small complaint when taking into account the possibilities that the unit opens up.

The Rockman

This interesting little unit from Scholz is entitled to a space all by itself for good reason-it's sort of the all-in-one effect for the recordist or performer, with built-in compression, reverb, chorus, distortion, and preset EQ positions. Unfortunately, there is no inherent ability to control the amount of these effects; it just provides a "produced" sound instantly. There is a lot to be said for this unit, but it isn't a true substitute for the other effects-just a handy way to get a thicker sound with out much thought. Still, it's hard to argue with the results one can achieve with The Rockman, particularly by plugging an electric guitar into it and feeding it directly into the board. The home recordist will find it a bargain at around $200.

Speakers There is no such thing as being objective about speakers, and every one's speakers tend to reflect their own personal tastes. For mixing, it is best to use speakers with as flat a response as possible. Don't be fooled into using tiny box monitors with 4-inch drivers simply because 4-inch speakers are used in street stereos where you want your record to be played. The mix that sounds good on your hi-fi system will also sound good on the small box, but the reverse isn't necessarily true.

Microphones

A hot mike in today's studio may tomorrow be outmoded, as the recording industry tends to be faddish in this department. AKG, E-V, Sennheiser, Shure, Sony and Neumann tend to stay within the parameters of what is acceptable, but personal taste and price will often determine your choice here.

Used pro audio shops will often have exceptional microphones at very low prices simply because a certain style has fallen out of a studio's favor, so this is a highly recommended way of acquiring a top-notch mike. I was able to acquire a couple of second-hand Sony mikes at a fifth of the list price because they were battery-powered units "and the clients used to always leave them on and burn out the batteries." As the saying goes, one man's ceiling is an other man's floor.

A Few Last Words

There is much to say about this subject, too much to detail in anything less than a very extensive book, so my apologies for any topics that I have breezed by. Line recording versus miked performances, baffling, micro phone placement, bouncing, stereo spread, and lots of other subjects of great importance haven't been touched, due to the limitations of space. Perhaps if there is a demand, possible future articles will delve deeper into some aspect of non-commercial recording. And as each studio device becomes more familiar to the public ear, a simplified version will probably become available to the consumer at a greatly reduced price.

But keep in mind that whatever the limitations of your home studio, the musical performance it captures and the person running it ultimately determine the quality of the tapes, not the equipment itself. The first Beatles and Stones records were made on two-and three-track recorders, in many ways more primitive than the studio machines many of you have in your basements. So get those patch cords in place and run with it-and if you're lucky you might even be making a record before you know it.

"Used professional mikes can be had at low prices."

----------

AKG mike

(Adapted from: Audio magazine, Sept. 1983)

Also see:

Home Studios--Do It The Pro Way (Part II) (Dec. 1984)

Studio In The Home (or: home in a studio) (Apr. 1973)

Build A Microphone Preamp (Feb. 1979)

Have DAT ... will Travel (Sept. 1991)

= = = =