by EDWARD TATNALL CANBY

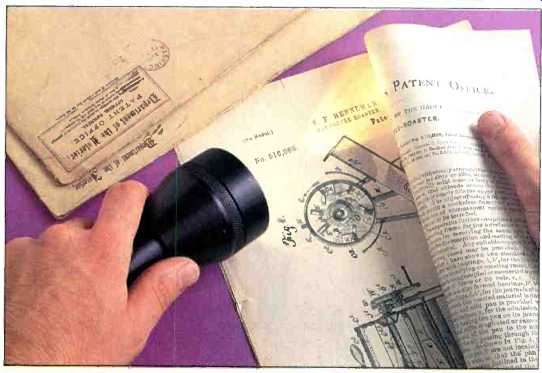

BUREAU-DRAWER DRAWINGS

DRAWER DRAWINGS IS IT FOR REAL?

Few of us enjoy having our leg pulled. And yet--sometimes we have to believe.

Sometimes we turn out to be right. Momentous discoveries or rediscoveries occur, like Schubert's "Unfinished" Symphony, dug up some 37 years after his death. Or the more than 30 unknown organ works by J. S. Bach rediscovered and performed within this last year. I've managed to hear them twice already. Or take the case of Sir Charles Wheatstone.

Remember the Wheatstone bridge? It was a well-known circuit used to measure electrical resistance. Sir Charles, born in 1802, was one of those dynamic, all-around inventors of the early 19th century-along with Faraday and many others of the Watt Ohm-Volta age and on to Hertz. It's a wonder we don't have a unit of measurement called a Wheatstone, with concurrent mega-Wheats and kilo Wheats. The man was a broad thinker and experimenter and, like many of his kind, a doodler of scientific ideas, on impulse or in the informal notebooks inventors seemed always to have with them in those days. He co-invented the Wheatstone-Cooke telegraph system, one of those competing with Morse; he made improvements on the nascent dynamo when the electric current was still mainly derived from batteries of voltaic and other cells. He was into photography, and in its earliest years it was he who suggested the stereo photograph--he is a father of stereoscopy.

And he invented the concertina! A musician of sorts. So to my present story.

One morning last spring I casually opened the latest issue of a mag called Stereo World. No, this is not a sudden, new addition to the hi-fi journalistic scene. It is the house organ of the National Stereoscopic Association, specializing in stereo photography.

Long-time readers will recall that my own interest in this art has always paralleled my later fascination with stereo sound. (Binaural reproduction, a channel for each ear, is the more exact counterpart to a pair of stereo photos, one for each eye.) My earliest homemade stereo picture, black and white on cardboard and printed by myself, dates from c. 1928, even before Keller's work at Bell Labs on sonic stereo.

It shows my father shepherding a batch of kids on a mountain walk. I was among them, lugging a camera ... . One glance at Stereo World and I went off like a bomb. All else was put aside. I put in a frantic call to the editors-for to my astonishment here was an audio story to end all audio stories, in a photographic mag and exclusive to it. Wheatstone, the father of stereoscopy, of course, accounted for that.

But did these people know what they had? Very likely not. Does anybody know his neighbor's field these days? Luckily, the call was not returned; I was, as you might say, in a tizzy, and hardly able to talk. But I didn't give up and I'm still there. It took me days to get back to some coherence.

Here was a group of unknown scientific sketches by Sir Charles Wheatstone, dating from the 1830s, rediscovered-where else?-in an old bureau drawer. Don't most old papers of the sort turn up in attics and bureau drawers? Old people die, their attics and bureau drawers are ransacked and out pop the most incredible things, including many genuine treasures. If not here, then from an equally fertile source, world-famous libraries, where anonymous misfiled documents lie for centuries untouched. It's all the same, bureau drawers and libraries-the Bach, above, came out of the Yale University library where it had been sitting for more than a century under some "miscellaneous" category, unrecognized. So, Wheatstone in a bureau drawer? What more likely.

Stereo World's writer, James Middleton, had done a superb journalistic job: There were the sketches, neatly reproduced as fragments, and there was a detailed explanation of the discovery that confirmed my interest via a remarkable variety of tie-ins with my own past life. The sketches actually turned up, I read, back in the early 1920s and were prepared for publication as a "scoop" in a then brand-new news magazine, no less than Time. At the last moment, the story was yanked out and a substitute put in its place. There had been objections. From lawyers for Thomas A. Edison, then very much alive. From the War Department, and its Secretary, name of Weeks. National security! And a conflict with Edison.

This was indeed a potential scoop.

The writer of the 1923 article was fired for his pains, it says. He went over to another new magazine, also still existing today, where he was, we are told, an employee for a half-century or so until his recent death in February of this year. But he never again tried to make his Wheatstone discovery public; after all, he had lost his job once, and risked the same again. Thinner reasons than that have kept great treasures hidden away by their owners.

Only after his death did the material surface-out of the same bureau drawer. That's the way the story goes.

Why so much fuss? Why national security? Sounds far-ftched. But if you glanced more than a moment at the actual drawings you would see why.

These were neat little doodles, not messy like Edison's (remember the famed drawing of the phonograph?) and very much in an early 19th-century style. Little men with tall top hats. They had the visible ring of authenticity. Not working blueprints, just quick idea sketches, the sort that often go no further than pencil and paper. But coming from Wheatstone? They just had to be significant.

One drawing showed an ingenious device for measuring ocean depth from a ship's deck. A vertical cannon would shoot a ball downwards. As it hit bottom, an impact wave would return to the surface where a large "tympanum membrane" would respond, and send a sound wave into a sort of ear trumpet listening device. A chronometer would measure the time lapse, which would give the depth. No mention of a muddy bottom, but perhaps the cessation of sound might be enough in that case. Can you see why the 1923 War Department might be concerned? Of course! This had intimations of sonar, no less. My own experience with exactly the same implication instantly told me this could be the truth. I myself got into similar trouble once, unwittingly, in this very magazine and on the very same basis.

Don't ask me where I had picked the idea up, but I somehow made mention of a reflecting ocean-depth measurement system not unlike radar. When that issue appeared I got a call from the U.S. Navy, and a group of impressive, white-coated Navy brass soon appeared at my New York apartment.

They questioned me for most of a long morning. Just how did I get the information in my Audio article? I said I didn't really remember, just read it in some magazine, maybe. They persisted. I laughed at the absurdity of it.

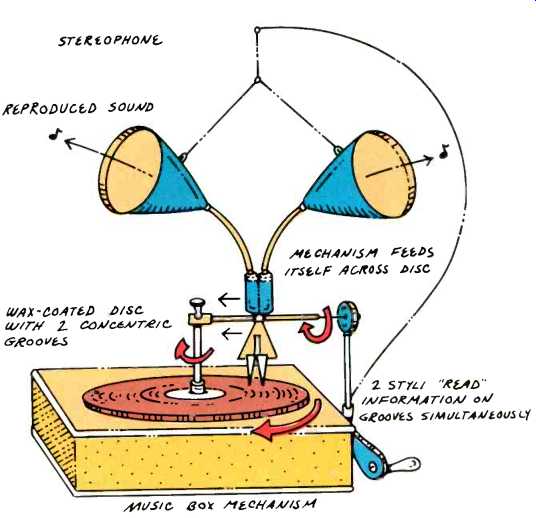

They did not laugh. They would not go away. It was, I assure you, very frightening. In the end, they departed and I heard no more. This story, I tell you, is God's truth. So I was quick to believe Stereo World. The War Department would surely object to Wheatstone's cannon idea as bad for security. (Yes, it was the Secretary of War, in peacetime. "Defense" was a later euphemism. And, yes, Weeks was the Secretary in 1923. I checked.) But on to audio. The drawing that made me really jump was of a sort of two-trumpet music box. It had a clockwork mechanism in the bottom (long since perfected as of the 1830s) and on top a round, turning table with, as it said, "concentric grooves" cut in wax, two of them. Overhead dangled a pair of styli, one for each groove, hanging from a sort of overhead screw lathe which moved them across, powered by the turntable itself. These led to tubes and to a pair of small horns or trumpets, suspended above. This device, the drawing said, should "read information" from the grooves.

Well, you may hoot in derision but the drawing is convincing. Indeed, nothing in it was impossible in, say, 1837. It could have been built, though surely it was not-like so many paper ideas surviving from the early inventors' files. It was an idea-sketch, no more. But can you understand why Edison's hawk-like lawyers might object and ask for a postponement for further inquiry? That 1837 drawing would have been a phonograph, some 40 years before Edison's. And stereo, too.

I also had experience in this direction, as did many another audio journalist. Edison himself is gone but the Edison people are still right there. With all due respect, I must say that there is no place more difficult to penetrate in a journalistic way than the present Edison domain, even for the simplest info on, say, the Original Phonograph. In 1977, its 100th birthday, I saw it, still there, in Orange, N.J., grimy and blackened, unobtrusively stashed off in a corner, while a resplendent reproduction took, so to speak, the limelight out front. (Audio ran a story on a similar model; see December 1977 issue.) I will say no more-but I could believe that Edison's people might well object to the publishing of this innocent little sketch until they had checked very thoroughly into the circumstances.

There was more, including a "portable music box" with tube and ear trumpet, nicely drawn and with humor, and even a set of "stereo ear muffs," with two forward-aimed horns coming out of them to carry sound. But enough.

There were remarkable further ties into my own life. In the Stereo World article, the issue of Time with the suppressed Wheatstone cover is shown. March 17, 1923, Vol. 1, No. 3. Yes, it is indeed the old Time, with the familiar pair of flowery columns on each side; yes, the black-and-white line drawing is right-they used them in early Time issues. There is the telegram from the "Sec-War" to Henry Luce of Time, on the correct-period telegram blank, and there too is Luce's note to colleague Britten Haddon ("Let me handle this") initialed HL, on Time stationery. Very convincing. It all checks out. The date, 'too, is correct: Time magazine had made its modest debut just two weeks earlier, on March 3, 1923. You should be able to find the March 17 issue--with a different cover story, of course--in any large library.

There's more. It happens that my father knew and, I think, taught the two young Time partners at Yale; he was their considerable adviser while the men were launching their news magazine. And in this very period Time shared a smallish office, back to back, with my father's own new magazine, the Saturday Review of Literature, saving both enterprises precious money.

As a small boy I was almost certainly in and out of that office, as I now can fuzzily remember.

Remarkably, a final aspect of the Wheatstone affair involves another of my close associations, the New Yorker magazine. It was to that then-new mag that the author of the Wheatstone piece and owner of the bureau drawer removed himself after being dropped from Time-says Stereo World. And it was right here that I began to have my doubts. I know the New Yorker too well.

I've always read it; I have a nephew on the staff right now. The employee in question, who wrote the original article and is said to have died last February, is named as Eustace Tilley. Does that ring any Tilley-bells with you? Eustace Tilley is the man who appears each year on the New Yorker anniversary cover, a dandy in a tall hat looking through a monocle at a butterfly. f have heard that he actually existed-in the early 19th century. Say around 1837? So I called Peter Canby, my New Yorker spy, to double-check.

No, Eustace was not an employee and did not die last February.

I've been amusing myself by showing Stereo World to numerous friends, deadpan. Most say it must be a hoax, yet each finds a different clue, and indeed, among us we've found many more. But for me it was Eustace Tilley who did it.

By all means, rush in your order for the May-June issue of Stereo World, while they last. Normally it's for members of NSA only, but the management says that readers of Audio may obtain a copy by sending $3 ($3.50 for first-class mail) to the National Stereoscopic Association, P.O. Box 14801, Columbus, Ohio 43214.

========

ADs

Onkyo

BEYOND CONVENTIONAL AMPLIFICATION ONKYO'S NEW REAL PHASE TECHNOLOGY

Today's speakers, with their multiple driver construction and complex crossovers, differ electrically from the simple resistive load used by amplifier designers to simulate the loudspeaker load. The actual load that is "seen" by the amplifier causes severe phase shift between the voltage and current sent to the speakers. This causes an audible loss of sonic clarity and dynamics.

Onkyo's Real Phase Technology uses not one, but two power transformers to correct this problem. A large high capacity primary transformer together with a special In-Phase secondary transformer prevents this phase shift, providing increased power output into tF e loudspeakerJoad as the music demands it. The result is clean, dramatic dynamics; musical peaks are reproduced with stunning clarity.

Now, the dynamic range of the music con be fully realized.

On the following pages, you'll find a complete explanation of the Real-Phase story.

Shown is our new A-8067 Integra amplifier, with Real Phase Technology and our exclusive Dual Recording Selector.

Artistry in Sound

200 Williams Drive, Ramsey, N.J. 07446

Real Phase To Preserve All the Complex Sound Field Information Contained in the Music

The Integra Series Sound

The elusive ideal in sound reproduction is to preserve and faithfully recreate all of the feeling of abundant energy and finely detailed presence of a live performance. Over the years, Onkyo has been tackling the myriad problems involved by developing new ways to solve each obstacle in the path to the ideal. As the name "Integra" implies, this new series of audio components makes full use of Onkyo's wealth of innovative technology to give you, the listener, a sound that is as close as possible to the original, a sound that can only be described as uniquely Integra.

--------An example of phase shift between current and voltage

---------Current and voltage phase shift vs. Frequency

Why Phase Accuracy Is So Critical

The relative difference in timing between the peaks and valleys in the left and right stereo channels, a characteristic called "phase," plays a major role in localization of individual sounds on the stereo "sound stage." If, for example, signals of the same frequency, strength and phase are sent to both speaker systems, the sound will seem to originate from a point precisely between the two speakers. If, on the other hand, the phase of the left and right signals does not coincide, the sound source will appear blurred or out of focus. Accurate stereo imaging, therefore, is possible only if the relative phase of the two stereo channels is not altered by the slightest degree during the amplification process.

How Phase Accuracy Is Lost in an Ordinary Amplifier

Because the load presented by a speaker system on an amplifier is not a purely ohmic resistance, there is an inevitable shift in phase between the voltage and current in the amp-to speaker signal path (see fig. 1). This phase shift is most pronounced around the speaker's bass resonance frequency, where the phase of the voltage and current are reversed (see fig. 2). Naturally, this same phase shift also exists between the voltages and the charging currents in the amplifier's power supply. These charging currents create a problem when the input signal contains very low frequencies (under about 120 Hz-precisely where voltage and current phase differ by the greatest amount) because the currents are made to fluctuate at the same frequency.

Electromagnetic flux generated by these "out of phase" charging currents often induces voltages of the same incorrect phase in the nearby driver stage (see fig. 3) through which the audio signal passes. These spurious, fluctuating voltages are amplified and then go on to the speakers. There they set the speaker diaphragms in a false kind of pulsating motion, which in turn causes phase inaccuracies and a particularly obnoxious kind of intermodulation distortion.

-----Block diagram of an ordinary amplifier

-----The Real Phase configuration

The Onkyo Solution-An In-Phase Transformer Onkyo dealt with the problem of phase dislocation by going straight to the root: the modulated, "out of phase" charging currents caused by very low frequency signal elements. If this undesirable modulation of the charging currents, which occurs every time a very low frequency signal is encountered, could be prevented, the problem would cease to exist. So Onkyo decided to "flatten out" these currents. This is done by taking advantage of the fact that the positive and negative charging currents are mirror images of each other. In the power supply section, an extra transformer (the "In-Phase" transformer) is placed between the power transformer and the capacitors. As the positive and negative charging currents pass through the two windings of this transformer, the unwanted peaks and valleys in the charging currents cancel each other out. The resulting current shapes are perfectly flat (see fig. 4). Another important benefit of having two equal charging currents is that no current flows in the common ground. This prevents another conceivable source of spurious signal fluctuations.

The Benefit---An Unprecedented Degree of Realistic Imaging and Low Range Definition

The audible benefits of Onkyo's Real Phase are striking.

First and foremost, these amplifiers create an auditory sensation that faithfully reproduces all the sound staging information in the input signal. Since there is no blurring or smearing, instruments and voices appear precisely focused and rock steady. Another advantage of Onkyo Real Phase is better speaker control in the bass range due to the absence of out-of-phase low frequency signals. You will notice that bass instruments sound much more tightly defined, with no annoying muddiness. It all adds up to unprecedented sound stage realism and image specificity.

------------Charging current in an ordinary amplifier , Charging current with Real Phase

A Truly "Digital Ready" Amplifier

With the appearance of compact disc players and other purely digital audio sources, manufacturers are calling all manner of amplifiers "digital ready." However, a closer look often reveals that this so-called "readiness" has been achieved simply by raising output power a few watts. Onkyo, though, builds digital ready amps which incorporate meaningful improvements in the way they operate. Real Phase is an excellent example of this policy. Because Real Phase guarantees that the output sound pressure waveforms precisely reflect the input signals, it also guarantees that the unparalleled purity of digital sources is faithfully preserved all the way to the speakers. Only an amplifier that incorporates such up-to-date technology is worthy of being called "digital ready."

--------------------

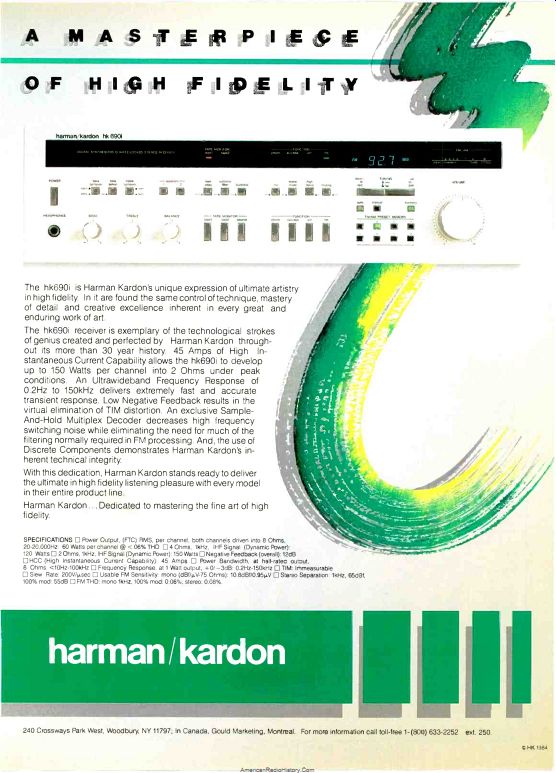

A MASTERPIECE OF HIGH FIDELITY

Harman/kardon hk 690i

The hk690i is Harman Kardon's unique expression of ultimate artistry in high fidelity. In it are found the same control of technique, mastery of detail and creative excellence inherent in every great and enduring work of art.

The hk690i receiver is exemplary of the technological strokes of genius created and perfected by Harman Kardon throughout its more than 30 year history. 45 Amps of High Instantaneous Current Capability allows the hk690i to develop up to 150 Watts per channel into 2 Ohms under peak conditions. An Ultrawideband Frequency Response of 0.2Hz to 150kHz delivers extremely fast and accurate transient response. Low Negative Feedback results in the virtual elimination of TIM distortion. An exclusive Sample And-Hold Multiplex Decoder decreases high frequency switching noise while eliminating the need for much of the filtering normally required in FM processing. And, the use of Discrete Components demonstrates Harman Kardon's inherent technical integrity.

With this dedication, Harman Kardon stands ready to deliver the ultimate in high fidelity listening pleasure with every model in their entire product line.

Harman Kardon... Dedicated to mastering the fine art of high fidelity.

SPECIFICATIONS

Power Output, (FTC) RMS, per channel, both channels driven into 8 Ohms, 20-20,000Hz: 60 Watts per channel <.06% THD

4 Ohms, 1kHz, IHF Signal (Dynamic Power): 120 Watts

2 Ohms, 1kHz, IHF Signal (Dynamic Power): 150 Watts

Negative Feedback (overall): 12dB HCC (High Instantaneous Current Capability): 45 Amps

Power Bandwidth, at half-rated output, 8 Ohms: <10Hz-100kHz

Frequency Response, at 1 Watt output, +0/-3dB: 0.2Hz-150kHz

TIM: Immeasurable Slew Rate: 200v/µsec

Usable FM Sensitivity: mono (dBf/µV--75 Ohms): 10.8 dBf/0.95µV

Stereo Separation: 1kHz, 6SdBf, 100% mod: 55dB

FM THD: mono 1kHz, 100% mod: 0.06%; stereo: 0.08%.

---------------

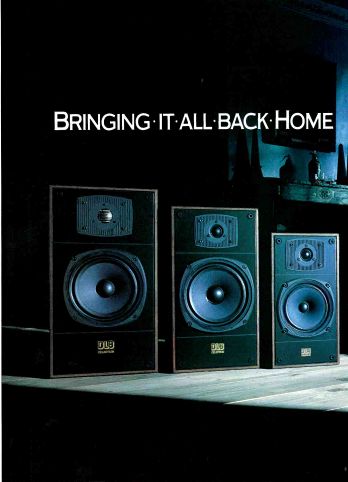

CELESTION DL

If you've ever been to a live concert, the chances are you've heard Celestion speakers.

For many years our speakers have been the choice of professional musicians who demand the ultimate in accuracy, definition, and reliability on stage.

The same demands from critical listeners at home led us to develop the SL6 and SL600, winning design awards worldwide.

The experience gained in creating live music and recreating it in the home now brings you the DL series from Celestion.

The DL series are compact, affordable speakers that deliver clean, transparent sound. They bring you the excitement of a large sound stage, yet they fit easily into your listening room.

Each model, DL4, DL6, and DL8, are laser-designed, a proven Celestion technique, to reproduce the full dynamic range of live concerts with moderately-priced audio systems. The latest technology, the thrill of the stage performance, are now available to every music lover.

From Celestion. The DL series that brings it all back home.

Celestion Industries, Inc.

Kuniholm Drive Box 521, Holliston, MA 01746 (617) 429-6706-Telex 948417 Outside Massachusetts 1-800-CEL-SPKR

Visit us at Booth 2-26 McCormick Center

----------------

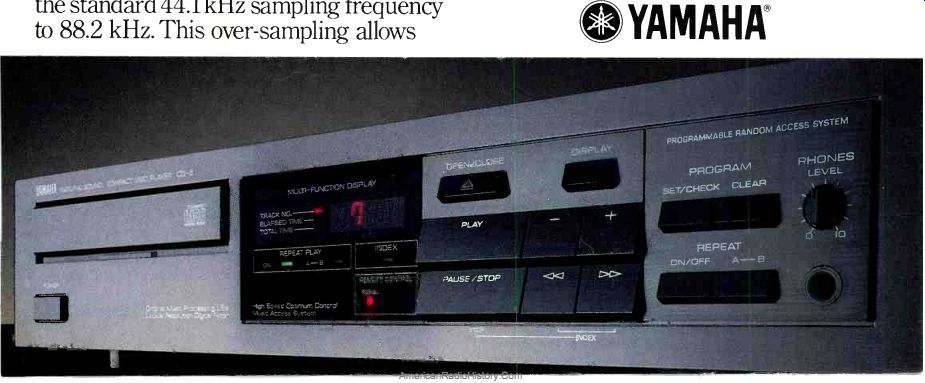

Play the hits.

With no errors.

By now, you're probably familiar with the virtues of compact discs. The wide dynamic range and absence of background noise and distortion. And the playback convenience.

Yet as advanced as the medium is, it's still not perfect.

Which is why you need a compact disc player as perfected as Yamaha's new CD-3.

The CD-3 uses a Yamaha-developed tracking servo control LSI to monitor its sophisticated 3-beam laser pickup. This LSI makes sure that horizontal and vertical tracking accuracy is consistently maintained. And that even small surface imperfections like fingerprints or dust will not cause tracking error and loss of signal.

Even more rigorous servo tracking control is provided by a unique Auto Laser Power Control circuit. Working with the tracking LSI, this circuit constantly monitors the signal and compensates for any manufacturing inconsistencies in the disc itself.

Then we use another Yamaha-developed signal processing LSI that doubles the standard 44.1 kHz sampling frequency to 88.2 kHz. This over-sampling allows us to use a low-pass analog filter with a gentle cutoff slope. So accurate imaging, especially in the high frequency range, is maintained.

We also use a special dual error correction circuit which detects and corrects multiple data errors in the initial stage of signal reconstruction.

So you hear your music recreated with all the uncolored, natural and accurate sound compact discs have to offer.

Another way the CD-3 makes playing the hits error-free is user-friendliness.

All multi-step operations like random playback programming, index search, and phrase repeat are performed with ease.

And visually confirmed in the multi-function display indicator.

And the wireless remote control that comes with the CD-3 allows you to execute all playback and programming commands with the greatest of ease.

But enough talk. It's time to visit your Yamaha audio dealer and tell him you want to play your favorite music on a CD-3. You can't go wrong.

Yamaha Electronics Corporation, USA, P.O. Box 6660, Buena Park, CA 90622

YAMAHA

------------------

"Frighteningly close to perfect"

OPTIONAL RC1 REMOTE CONTROL UNIT

The Atelier CD3 Compact Disc player is the newest example of the ADS philosophy: Never rush to market with a "me too" product.

Take the time and trouble to design an original.

We did.

We used 16-bit digital to analog converters for each channel and two-times oversampling to insure exceptional accuracy, low distortion, and outstanding signal-to-noise ratios.

We developed digital/analog filtering that not only eliminates sampling and conversion noise but allows less than 2 degrees of phase shift from 20-20 kHz.

We designed an advanced error correction system with a unique variable correction window. This system focuses only on the data in error and eliminates unnecessary large-scale correction of the music signal.

The resulting sound of the CD3 is smooth and clear, free from the shrillness often associated with less advanced CD players. Frequency response, as Dig/ta/Audio described it, is "frighteningly close to perfect." Of course, the CD3 shares the rational, uncluttered design of other Atelier components. Front panel controls are simple and logical. More complex functions, such as indexing, time and track display, toggling and 30 selection programming are hidden on a push-to-release pivoting panel.

An optional remote control unit, the RC1, is available for the CD3. It has the capability to control all future Atelier components.

The CD3 is now at your local ADS dealer. Listen to one, touch one, see how close to perfect a CD player can be.

For more information or the location of your nearest ADS dealer, call 800-824-7888 (in CA 800-852-7777) Operator 483.Or write to ADS, 560 Progress Way, Wilmington, MA 01887.

The new ADS CD3.

-------------------

= = = =

Also see: