DAT WHICH IS TO COME

Double Standards

The Japanese industry group which has been considering standards for home digital audio tape (DAT) has finally approved two standards, one each for fixed-head and rotary-head recorders. The rotary-head version will probably be first out of the starting gate. It can't easily be made as small as the fixed-head version (a concern of car-stereo makers and portable cassette deck users), but its head drum can be produced using familiar VCR technology. The other type uses a thin-film head which is hard to mass-produce, at least with current techniques.

Both formats are stereo, using 16-bit linear quantization and 48-kHz sampling (with CD-style 44.1-kHz sampling also available on the stationary-head type). The stationary head (S-DAT) version will flip over, like today's analog Compact Cassette, recording either 35 or 45 minutes per side, depending on the tape thickness used. The rotary-head (R-DAT) version will record 120 to 150 minutes, in one direction.

Both formats will use the same tape width-3.81 mm or 0.15 inch-as the Compact Cassette. The cassette shells will resemble each other in size and shape (see Table), but you may be able to store quite a few more digital than analog cassettes in the same space, depending on the packaging used. The S-DAT is only 58% as large as the Compact Cassette, and the R-DAT is only 53% as large. It's the spinning head drum, not the cassette shell, that will keep R-DAT players from getting quite as compact as S-DAT players.

----------

Comparative sizes (in mm) of digital and analog tape cassettes.

Format | S-DAT | R-DAT | Compact Cassette

Length 86 73 100,4

Width 55 53.5 63.8

Depth 9.5 10.5 12.1

Volume (cc) 44.9 41.1 77.5

---------

Up to the Nation's Attic

Like many an audiophile, I'm also a computer hobbyist-have been, in fact, since 1976, when I got an Altair, the first personal computer to make a real impact. Since then I've gone on to more manageable machines (TRS-80s and Kaypros), so I just donated the Altair to the Smithsonian Institution. (If you have similar equipment you'd like to donate, contact Dr. Uta Mertzbach at the Department of Mathematics, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 20560, to see if they'd like it.) Walking through the museum afterwards, I noted very little in the way of sound equipment, which started me thinking about various pieces of sound gear that have passed through my hands over the years, items which should, perhaps, have wound up in the Smithsonian.

My favorite was my first good turntable, a Weathers kit that sold for about $50 (less arm) and was about the simplest design possible. To get good speed regulation cheaply, it used an electric-clock motor; since that had little torque, the platter was made of a thin aluminum stamping.

(Resonance? We didn't ask, in those days.) Since the platter was so light, the drive could be a thin gum-rubber wheel, permanently pressed against the platter's inside rim. The soft rubber never set in any shape, so it never developed permanent flat spots. The bearing was a single needle, running in bronze bushings. A triumph of simplicity and elegance-at a price that even a young college student could afford.

My first good preamp, a Heath WA-P2, had turnover and roll-off controls for all the then-current (and past) recording equalization curves. I only let it go because I replaced the Heath W-5M amplifier from which the preamp drew its power. My replacement amp was a Dynakit Mark III, a 60-watt tube unit that looked fancy but didn't cost much. My roommate supplied the Mark Ill for the other channel, plus an H. H. Scott stereo preamp. He also had a Scott "binaural" tuner-so-called because its AM and FM sides had separate outputs and tuning controls; stereo broadcasts then had one channel on AM and one on FM, while the FCC debated which FM multiplex system to accept.

The stereo preamp I wanted back then was the Lafayette, which had independent left and right controls for everything-even for input selection.

(The idea, as I recall, was to let you pipe two different mono signals to two separate rooms when you weren't listening in mono.) My first tape deck, as I've said before, was a Magnecord PT-6, one of the earliest professional decks, probably a museum piece even then, and certainly one now. Then there was an Advent cassette deck-the first, I think, with Dolby NR. I also had, back then, a I-o-o-n-g SME tonearm (we cared more about tracking error, in those days, than about moving mass, and that long SME was lighter than some shorter arms-of that time, anyway). I've had a lot of other gear over the years, of course. But those are the ones which strike me as museum worthy.

Inching into MTS

MTS stereo is definitely coming. As of July 30, at least 60 to 65 percent of U.S. viewers were within reach of at least one stereo-equipped station, according to Television Digest.

However, don't expect to be trampled in the rush. For stations it's a big expense-a minimum of about $30,000 just to ready the transmitter, and as much as $1 million to equip a mono-only station to originate as well as relay stereo. There isn't that much stereo programming yet, and most of the TV sets in use have neither built-in stereo decoders nor jacks for simple add-ons. Hardware to solve that problem is coming, of course, but there are other barriers.

Few VCRs, as yet, are equipped to pick up stereo, even if they can record and play it. If you want stereo, you feed in stereo sound from some external source or get a prerecorded tape with stereo sound-but you can't tape it off the air. By the time you read this, most major suppliers should have full-stereo video recorders on the market, but the vast majority of VCRs in use won't have that capability.

Nor will it do you much good to have MTS-capable equipment if you're watching over cable, as more than 40% of all U.S. homes now do.

Cable systems do send stereo by other means (chiefly via FM carriers on locally unused frequencies), but few have the bandwidth available, in either their head ends or the decoder boxes in subscriber homes, to pass the MTS subcarriers. Not too surprisingly, Zenith (one of the MTS system's developers) has a full line of stereo-compatible cable head-end and decoder equipment; now all they have to do is convince the cable companies to purchase it. Networks at first took the position that the FCC's "must carry" regulations meant cable companies had to carry everything in the broadcast signal, including the added audio information. The FCC, however, seems disinclined to press the matter-it has, in fact, dropped existing "must carry" provisions, a move which has local stations fearing they'll be cut off from local cable viewers.

The problems of 60-Hz intercarrier buzz which already plague some sets and broadcasts (especially when the picture has a lot of white in it) will plague them even more in stereo, and more still in the second audio program (SAP) channel. This problem may prove temporary, however; I note that National Semiconductor's stereo TV ICs include sound amps designed to reduce intercarrier noise.

Meanwhile, what of the programming considerations? Even Japan, which has had stereo TV longest, has far more mono than stereo programming. Of that, music and sports predominate, with occasional other applications, such as using the system's "bilingual" capability to offer a choice of commentators, one more detailed than the other. ( Japan's system, unlike ours, cannot be used for both stereo and bilingual information simultaneously.) Other possibilities include special narration for the blind, and music shows with vocals on one audio channel and no vocal on the other, for karaoke fans who want to sing along.

Drama, of course, is an obvious candidate. But if a camera angle is reversed, the actors' audible positioning will have to shift, too-not just right to left, but nearer and farther, too (i.e., louder and perhaps less reverberant when closer to the camera). The mechanical aspects of these problems can be handled by automation, but there will still have to be some intelligence behind the automation to make sure it does the esthetically proper thing. Though the movies seem to be developing a stereo sound esthetic, it's still new to people in TV. And the problem of maintaining mono compatibility is less critical for the movies than for TV (most of whose listeners have only mono capability). I expect stereo to make its first and strongest showing in commercials. Ad people have lots more to spend per minute of air time, and a gimmick that will hook more viewers--especially the upscale ones who will predominate among stereo listeners for a while, yet-will be hard to resist.

Live End, Cat End ... Cured?

While I haven't yet had time to implement a dead end in my new home's listening room, I have gotten two pieces of reader advice about keeping my cats off the acoustical treatment.

W. E. Craig of Oak Park, Ill., suggested a scratching post. I tried that a decade back, with my previous batch of cats, but they ignored it; my current cats, however, like it fine. It doesn't eliminate their scratching elsewhere, but it cuts it drastically.

J. M. DeMoor of Aiea, Hawaii, says he saw a pet-training expert on TV claim that inflated balloons on the furniture would keep the cats away: "They only experiment once!" On the other hand, who wants a room full of balloons, except at parties? The way the room is shaping up, however, the walls behind the speakers will be covered with record cabinets, so I can't put acoustical treatment there. The side walls have more cabinets, an archway into the hall, and a window, which limits my options further. I guess I'll get heavy drapes for the window, and perhaps put some acoustical treatment on the ceiling ... where the cats couldn't get at it, in any case.

Keeping Your Distance It's getting to the point where half the companies who make more than one type of stereo component offer a single remote-control transmitter that will operate several of those components at once (ADS, B & O, Kyocera, Revox ...). The other half are working on it. And everyone who makes integrated audio/video systems offers such controls as a matter of course.

But where does that leave audiophiles who'd like remote-control convenience, but prefer to pick and choose their components rather than stick to one maker's line? Pretty far out in left field ... until lately. A while back, I pleaded for a universal remote control, one which could be used for audio and video components from diverse manufacturers. Well, now there is one.

This doesn't mean that manufacturers have yet gotten together to define their remote-control codes (though the EIA still has a committee working on that, with a target date of 1987). Instead, General Electric has devised a $150 gadget called Control Central (Model RRC600), which memorizes the codes your existing components use. You place the component's remote control head-to-head with the Control Central and run through the old remote's functions, and Control Central learns all its command codes. An LCD display on the RRC600 can be programmed to show what functions you're commanding. Up to four components' codes can be memorized.

This presumes, of course, that your components already have wireless remote-control capability. Nowadays, most tape decks, VCRs and videodisc players, plus many receivers and several turntables, do have such capability-but virtually all amps, preamps and tuners don't. If that's your problem, there's not much you can do about the tuner, but you can add remote control of volume, balance, muting, power, and a few other things.

One way is with AR's $160 SRC remote control (reviewed in Audio, January '85), whose "other things" include input/output loops for a tape deck and an external processor. And who's to say you couldn't use both of those as tape loops or as EPLs, or ignore the output function and use them only as remotely selected inputs? A second way is with a somewhat similar control system, the 50/2000 ($155), from Digital Audio Control of Mountain View, Cal. Instead of the AR's in/out loops, DAC's Model 50 receiver has one monitor output and three auxiliary high-level inputs. This means you can choose among four inputs (the three on the remote unit plus whichever one your amplifier is switched to), but you can't monitor recordings or patch in an equalizer.

As if to make up for that, the system has its own treble and bass control, plus switchable loudness compensation. A "Flat" key on the Model 2000 transmitter automatically neutralizes those alterations and centers the balance. You can also switch from mono to stereo.

To their credit, wired remotes are hard to lose-you can always trace them by their wires-but their chief advantage is that wires go around corners better than light beams do.

You can run a wired remote to places where a wireless one wouldn't reach, such as another room. (The wireless multi-room systems, such as those from B & O and Revox, run wires to remote infrared receivers in the other rooms, to pick up the hand-held controllers' beams.) Audio Command Systems of Rockville Centre, N.Y., has for years been doing custom audio installations with such wired remote systems. Now they have a remote, called Mediacom, designed for sale on its own. Mediacom uses wireless controllers, with a big command terminal in the room where the main system is located and smaller terminals wired to it from other rooms.

You can select any of several audio and video sources, activate your tuner's station preselects, operate your tape deck's transport functions, turn speakers on and off in the room where you are or elsewhere in the house, and even simultaneously play two different signal sources in different rooms (or more, if you patch in local sources in specific rooms). Mediacom can be matched to any existing or future components. It's done by changing interface cards in the main control console and, if the components have no wired control inputs, by modifying the components to accept remote commands. Some interface cards may have to be custom made, which would add to the system's already hefty price tag.

The basic command terminal is $2,400, wireless controllers are $179 apiece, and remote terminals are either $645 (for wall-mounted units) or $745 (for table-top ones). A simpler terminal panel, with only volume, speaker on/off and signal-select controls, is $150. The 15-conductor cable which connects the rooms is about 400 per foot. Though Mediacom literature sounds as if it's aimed at the end customer, I suspect that most sales will be to (or through) custom installers.

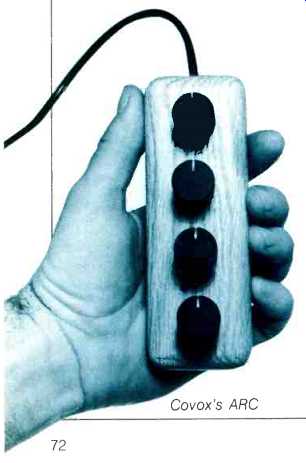

On a simpler note, Covox, of Eugene, Ore., has a wired remote control, the ARC, with balance, volume, bass and treble functions on the remote, plus a tape-monitor loop switch on the base unit. Only control voltages, not signals, go through the wire, so you can add 20-foot extension cables to bring the control into other rooms. The system is $99, and extension cables are $10 each.

(adapted from Audio magazine, Oct. 1985)

= = = =