PHILOSOPHIES TO COUNT ON.

Graphic Contrasts

Some audiophiles find digital sound offensive to their ears; others, I suspect, find it offensive to their philosophies. For the philosophical bases of analog and digital are very different.

Analog builds models, or analogs, of the desired information, on the optimistic assumption that our modeling technology is infinitely perfectible. (That also means it's never quite perfected, which leaves lots of room for us to have fun in tinkering with it.) Digital starts from the cheerful admission that total perfection is impossible, then goes on to assume that we can, by choosing the specific degree of perfection we can live with, achieve it-not approximating perfection but perfecting our approximations.

Analog's history has borne out its premise. Today's LPs are still based, rather obviously, on Edison's century old-but vastly improved technology. We now have wider frequency response, lower noise and less distortion, all in a medium that holds more hours of music in less space and costs less to manufacture than Edison's cylinders.

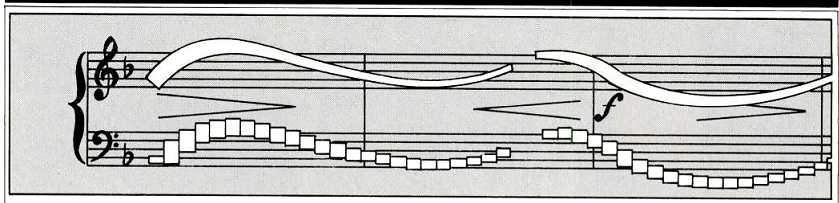

But the more we progress, the harder it gets to improve. The lower the distortion, the harder it is to reduce, whether we mean cutting it by a fixed numerical ratio (such as half) or making an audibly significant improvement. Cut distortion from 10% to 1% and you're a hero-cut it from 0.001% to 0.0001% (which is a great deal harder) and who cares? Analog and digital philosophies, unlike most others, can be graphed.

The analog approach to perfection may be described, without hyperbole, as a hyperbola-a curve which swings up in an ever-steepening arc.

Label the vertical scale as effort needed and the horizontal scale as the quality that effort yields, and you'll find perfection is an asymptote, a point that curve grows ever nearer to without quite touching. Mathematically, perfection can be reached-but by that point, the curve's upward slope, the effort involved, has become infinite. Perfection cannot be attained in finite time, or with finite resources.

In practice, though, we eventually reach a point of "good enough." Once frequency and phase response are flat to 15 kHz, further improvement is unnecessary for most listeners; once flat to 20 kHz, then very few listeners will be able to recognize further progress. Flatten the system out to 100 kHz, and even the most optimistic view of human perception would concede that no further increase would be distinguishable. So we draw up ideal specifications (such as "1% THD" or "20 to 20,000 Hz"), creep up on them and then, once they're attained, reset our sights a little higher.

Digital takes the idea of "good enough" as its foundation, setting its limits with one eye cocked on what is ideally desirable and the other on what's practical. Digital naysayers maintain that those limits have been set too low. That's a pity, if true, since digital systems must jump, not creep, to progress; a diagram of digital philosophy would show stepwise progress between flat plateaus. In other words, the only way to raise our current technology's limits would be to come up with an entirely new digital system, using faster sampling and more bits. Such a system could be implemented now, but only at forbidding cost and with the elimination of the Compact Disc's compactness.

Even digital enthusiasts concede that today's systems only reach their built-in limits in the digital domain.

There's still a trace of slippage during analog-to-digital and digital-to-analog conversion, and there's still some imperfection in the analog stages of the digital hardware. (By definition, remember, analog is never perfect, just perfectible.) These latter imperfections can and will be ironed out, but only by the time-honored of creeping up on the ideal.

Audiophilia grew up in analog surroundings. So many audiophiles feel uncomfortable-consciously or unconsciously-with a system which, however good, admits no further improvement, let alone ultimate perfection. "The sky's the limit" seems rather confining, once you've reached the sky.

Audio hobbyists have a more concrete reason for discomfort: The closed nature of digital systems seems to prohibit the tinkering and finicky adjustment which make analog such involving fun.

For the phonograph, you can buy an infinite variety of mats, cartridges, styli, levels, arms, clamps, isolating stands, de-isolating stands, dampers, cables, separate lubricants for records and for styli, and separate cleaners ditto. You can change tracking force, anti-skating, cartridge alignment, and vertical tracking angle.

And so on.

For the Compact Disc, the options are far fewer. Some audiophiles claim that a disc will sound better if you put another disc on top of it ... if your player accepts double discs without jamming. And you can now buy special cables, phase-correction boxes, isolating feet (or players with them) to reduce the chance of microphonics, and enough CD cleaners to make you forget you're supposed to be able to clean the discs with a damp cloth. (In fairness, the best CD cleaners do ensure that all strokes are radial, across the signal paths, rather than circular, following these paths around the disc; that is important.) What about the thrill of custom-tailoring your system, buying and assembling the digital equivalent of tonearm, turntable and cartridge? The day could come when, instead of buying separate turntables, tonearms, headshells, cartridges and mats, the audiophile will purchase separate CD transports, lasers, error-correction ICs, D/A converters, etc. It could-but I don't consider it too likely. The price of such custom complexity would be far higher than the phono equivalent and far less audible.

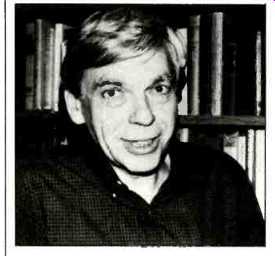

Coda: Norman Eisenberg

Norman Eisenberg of Stockbridge, Mass., audio critic and writer, died on July 12th at the age of 63. Though he had written only irregularly for Audio, Norman had a long and distinguished career in the field. At one time he was the audio columnist for Saturday Review. In 1960 he joined High Fidelity as Technical Editor, later becoming Audio-Video Editor and Executive Editor during the 15 years he spent with that magazine. He also edited Stereo Quarterly and several High Fidelity annual publications. At the time of his death, he was a syndicated audio columnist for the Washington Post, the Newark Star Ledger and the Detroit Free Press newspapers, and for Playboy and Ovation magazines.

It was a pleasure editing the articles Norman wrote for us-not just because he was a good writer, but because he'd done the same for me, many times, in years past. He was a good editor to work with-not uncritical, but clear and constructive in his criticisms, and able to understand an author's point of view.

He was also good company on the many trips we shared to audio labs and factories overseas. He loved not only audio but music. He will be missed.

(adapted from Audio magazine, Nov. 1985)

= = = =