Manufacturer's Specifications

Frequency Response: 30 Hz to 15 kHz, to 16 kHz with CrO2 tape, and to 18 kHz with metal tape.

Harmonic Distortion: 1.0 percent for 333 Hz at 0 dB.

Signal/Noise Ratio: 56 dBA, 59 dBA with CrO2 tape; 66 dBA with Dolby NR/HX, 68 dBA with CrO2 tape.

Separation: 40 dB Erasure: 70 dB.

Input Sensitivity: Mike, 0.25 mV; line, 60 mV.

Output Level: Line, 550 mV into 50 kilohms.

Flutter: 0.07 percent wtd. rms, 0.13 percent wtd. pk.

Speed Accuracy: ± 1.0 percent.

FF & RWD Times: 100 seconds for C 60.

Dimensions: 16.5 in. (420 mm) W x 4.5 in. (115 mm) H x 9 in. (230 mm) D.

Weight: 9.5 lbs. (4.3 kg).

Price: $279.00.

This just-released NAD stereo cassette deck is certain to get a fair amount of attention because of its low price and its metal-tape compatibility, to say nothing about its peak-reading meters. The bigger news, however, is that the 6040 incorporates the recently developed Dolby HX headroom extension circuitry, along with the standard Dolby B NR. The only indication of this on the front panel is the Dolby NR/HX designation above one of the large, square push buttons.

There are six other buttons in the same row for MPX Filter, Memory and tape-type selection-- Normal, CrO2, FeCr and Metal. Just a light touch is required for actuation, and there is a green LED indicator to show when Dolby NR/HX is on. The dual-concentric record-level pots are friction coupled, and the large knobs facilitate adjusting one channel relative to the other. There is a "Peak Reading" designation below the meters, though "VU" is actually printed on each face. By this time each manufacturer and, we hope, each reader should know that a meter meeting the VU standard is average responding. A true VU meter cannot read peaks--by design. A better label for non-VU meters would be simply, "dB." With the white scales and good illumination, everything was very legible, though the needles seemed a little thin.

The tape-motion controls are lever-type with medium force required for actuation. They are all of the same size, and the designations above, and other panel marking, were easy to read except in dim light. The cassette compartment door opened smoothly with a push of Stop/Eject. With slight attention to miss a step on the top, drop-in loading was simple. Access for maintenance tasks was very good with the door open. Just to the right are the tape counter and its reset button and the red Rec indicator. The push-button power switch and the jacks for headphones and left and right mikes complete the front panel.

On the back panel are the line-in/line-out jacks and a DIN socket. Access to the interior was gained with the removal of the steel top and side cover and the hardboard bottom cover. The soldering was very good in general, with some flux residue at external connection points of the single, large p.c. board. (Actually there were a couple of very small cards with small parts of the circuitry.) There was no identification of any of the parts, and the adjustments were not labeled. The single-motor drive was simple in construction, but it had fairly good rigidity. The power transformer was smaller than in many decks, but there was a lot less circuitry than in a logic-controlled unit, and a later check showed that in use the transformer became just warm to the touch.

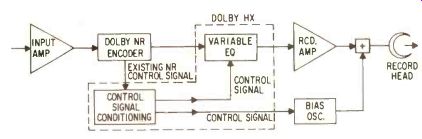

Fig. 1--How Dolby HX is incorporated into a deck equipped with Do by Type B noise

reduction.

Circuit Description

As most readers have probably not had the opportunity to read much material on the new Dolby HX scheme, we will include a brief discussion of it here. First, a review of the present situation shows that most of the decks in use have Dolby Type B noise reduction, just about essential for the cassette format to make it as a high-fidelity medium. (We're not forgetting other schemes such as JVC's ANRS, dbx II and Nakamichi's High-Com II, but they are not central to the story being told here.) With improvement in both tape formulations and the decks to use them, noise levels were reduced, MRLs became higher, and signal-to-noise ratios approached 70 dBA. A problem remaining, however, was a general limitation in the amount of high-frequency energy that could be recorded. Tape saturation, self-erasure, and excessive distortion were all involved. It can be seen that there would be an advantage in adjusting bias and equalization to match each type of music material for the best results, and that's what Dolby HX does dynamically--during the process of recording.

Follow the signal paths of Fig. 1 while you read this quotation from a Dolby brochure: "There is a way to get the best of both worlds, however; it involves, among other things, a signal-controlled varying bias. This is the main principle under lying Dolby headroom extension (Dolby HX), a technique that alters the strength of the bias in accordance with the immediate requirements of the program material. Most of the time, when demands on the high-frequency signal-handling capability of the recording system are low or moderate, the bias is kept comparatively high for optimum performance at mid and low frequencies. But when large amounts of high-frequency energy are present, a control signal (which is de rived from the Dolby B-type noise reduction processor) causes the Dolby HX circuitry to reduce momentarily the bias, going to the record head and also to make the necessary changes in the recording equalization to maintain flat frequency response. Thus, high-frequency headroom is significantly extended, exactly when it is needed and only when it is needed. With Dolby HX used in this way, it is possible to realize a headroom increase on the order of 10 dB at frequencies above 10 kHz before tape saturation occurs, and with no audible sacrifice of performance at other frequencies."

The above statements are certainly impressive, and there was particular interest to see how much extension was obtained and whether the bias and EQ changes were matched well enough for flat responses. The results of a number of tests are reported below.

Lab Measurements

With TDK 120-uS test tape, the play responses were very close with the exception of fringing effects at 40 Hz and below. Dolby-level playback was right on the meter reference at "-2." Tape play speed was about 0.3 percent fast.

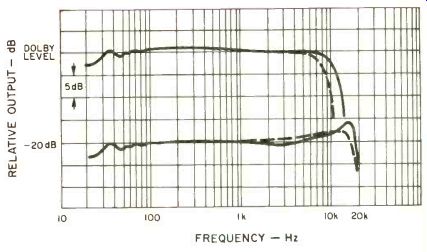

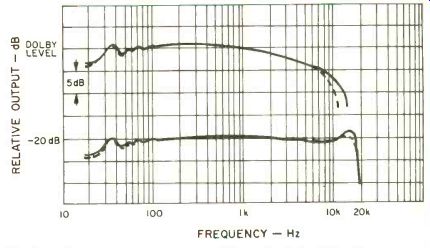

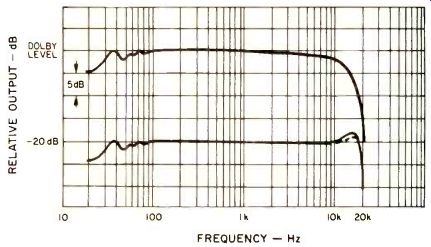

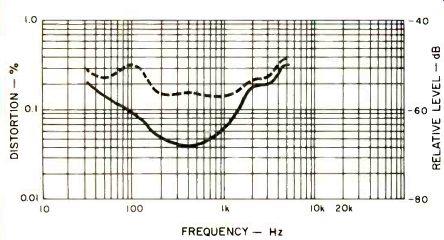

Tests with pink noise and a ''/3-octave RTA showed that very good responses were obtained with Ampex Grand Master I and MPT, Maxell UD XL-I and UD XL-II, Memorex High Bias, RKO Broadcast I, Scotch Master II, Sony HFX, SHF, FeCr and EHF, TSI (Agfa), and TDK D, SA and MA-R. The usual battery of tests were conducted with Maxell UD XL-I, Sony LHF, and TDK MA-R. Swept record/playback responses were plotted at Dolby level and 20 dB below that, both with and without Dolby NR/HX. The results in Figs. 2 to 4 and Table I show immediately, and obviously, the improvements gained with the HX design.

Fig. 2--Frequency response with and without (---) Dolby HX/NR using Maxell

UD XL-1 tape.

Fig. 3- Frequency response with and without (---) Dolby NR using Sony EHF

tape.

Fig. 4--Frequency response with and without (---) Dolby HX/NR using TDK MA-R

tape.

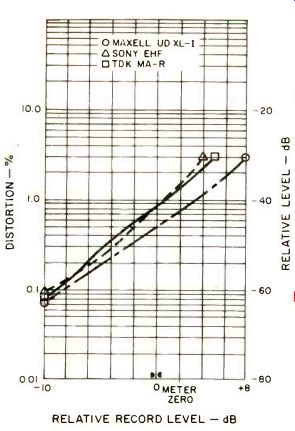

Fig. 5--Third harmonic distortion vs. level in Dolby HX/NR mode at 1 kHz with

Maxell UD XL-1, Sony EHF, and TDK MA-R tapes. (Note: NAD does not use HX circuitry

on metal tape.)

Fig. 6--Third harmonic distortion vs. frequency with and without (---) Dolby

NR/HX mode at 10 dB below Dolby level using Maxell UD XL-I tape.

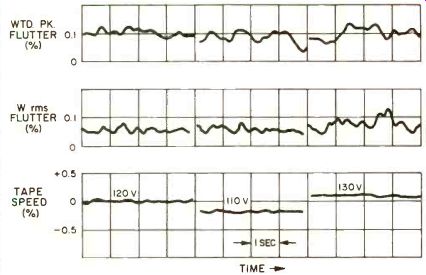

Fig. 7--Tape play speed vs. line voltage, and wtd. rms and wtd. pk. flutter

(three trials each).

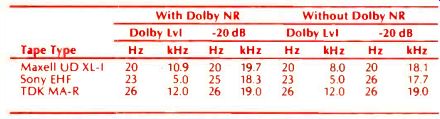

Table I-Record/playback responses (-3 dB limits).

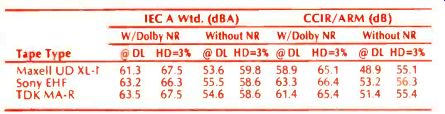

Table II-Signal/noise ratios with IEC A and CCIR/ ARM weightings.

First of all, it is important to note that in each and every case, the high-frequency response extends further with NR/ HX than without, except for metal tape where NAD has not applied the HX circuitry. In the past, we have all become quite accustomed to seeing the reduction in the high-end limit with NR switched in. The improvement with NR/HX is most impressive with UD XL-I at 0 dB, where the limit was extended from 8.0 to 10.9 kHz--a significant change. With the more music-like pink noise as the source and a meter level of "+3," or 5 dB above Dolby level, the response with NR/HX was better by these amounts: 3 dB at 8 kHz, 5 dB at 10 kHz, 8 dB at 12.5 kHz, 12 dB at 16 kHz, and 13 dB at 20 kHz. The NR/HX display was flat to 16 kHz, even with this very-high level. The responses were generally quite flat in the important 100-Hz to 10-kHz region, though the 16.5-kHz peak with Maxell UD XL-I at-20 dB is a bit much, and the general droop at higher frequencies at Dolby level with Sony EHF and other Type II tapes indicated a recorder limitation.

Phase jitter in the playback of a 10-kHz tone was 40 degrees, typical for a cassette deck. The multiplex filter was 3 dB down at 16.4 kHz and a good 32.7 dB at 19 kHz. Bias in the output during recording was very low. Separation between tracks of the stereo pair was an excellent 56 dB at 1 kHz, and crosstalk and erasure at the same frequency were down more than 80 dB, also excellent results. Erasure at 100 Hz with met al tape was more than 65 dB, one of the better results to date.

The third harmonic distortion level was measured for each of the tapes at 1 kHz in Dolby NR/HX mode from 10 dB below Dolby level to the point of three-percent distortion. The curves in Fig. 5 are fairly linear, but there were some reversals in slope, with causes unknown. HDL2 was quite low, and HDLS was very low at each point checked. The distortion levels without NR/HX were about twice as high, a greater difference than measured at any time in the past. It would appear that the new scheme was "better-than-ever" in reducing distortion. Then, a look was given at HDL3 at -10 dB from 30 Hz to 5 kHz with UD XL-I tape, with and without Dolby NR/HX. Figure 6 tells an interesting story. First of all, the distortion without Dolby is quite good across the band. The addition of NR/HX, however, reduces the distortion at each point, especially the region around 100 Hz to 1 kHz, with just 0.04 percent HDL3 at 400 Hz--an excellent figure!

The signal-to-noise ratios were measured with both IEC A and CCIR/ARM weightings, and the results are listed in Table II. Note that the highest figures with IEC A weighting go with Maxell UD XL-I and TDK MA-R, but with CCIR/ARM weighting Sony EHF is the leader. As all of the results are excellent, tape choice would be based upon other factors normally. Input sensitivities were 87 mV for line and 0.20 mV for mike. Input overload was about 31 V for line and 16.1 mV for mike. Output clipping occurred at +14 dB relative to meter zero. The line input impedance was 40 to 68 kilohms over most of the range, falling slowly to 28 to 37 kilohms at 20 kHz, with the lowest impedances at each frequency with the input pot fully CW. The pot itself showed tracking within a dB for the two sections from maximum down 60 dB--excellent. Line output was 750 mV into the rated 50 kilohms, falling to 605 mV with the IHF 10-kilohm load. Headphone drive was 40 mV with 8-ohm loading, which generated a good volume with each of the phone sets tried.

The meter scales were very accurate from "-3" to "+4." The lowest part of the scale was about a dB in error, and there was a deflection limit at "+4.5," just shy of the last marking, "+5." The meter frequency response was 3 dB down at 17 Hz and 20.7 kHz. The dynamic response of the meters was checked against IEC Standard 268-10 for peak program meters. With a 3-mS burst, the response was just 3 dB down, meeting the standard. With a 10-mS burst, the-2.3 dB indication was just below requirements of the standard. The 20-dB decay time was 1.5 S, within the standard. Deflection in creased with positive d.c. shift added to the tone burst, but only very slightly with a negative shift added. Overall, the meters were classified as true peak reading, with minor deficiencies.

A 3-kHz tone was recorded with the line voltage at 120 V. In playback, tape speed was measured at that voltage, and then at 110 V and 130 V. With the lower voltage, speed dropped about 0.2 percent, and the higher voltage caused an increase of 0.1 percent. These changes would not normally be significant (a semi-tone equals ±5.9 percent), but might have some importance to a user in an area with poor line-voltage regulation. There were three trials each for measuring wtd. rms and wtd. pk. flutter. Typical figures were 0.065 per cent wtd. rms and 0.095 percent wtd. pk. Wind times were 105 seconds for a C-60, slower than most decks, but the wind was smooth. The time from run-out to stop was about 4 seconds in wind and 2 seconds in play. It was pleasantly surprising to find that it was possible to go from any mode to any other without going through Stop. This was definitely different from the interlocking tape-motion controls in other decks of lever/key design. For example, it was quite easy to do flying start recording. All you do is hold down Play and push down Rec.

Use and Listening Tests

Some time was spent switching from one transport mode to the other, ignoring all the rules about going through Stop when using a deck with direct mechanical actuation. No jam ups occurred, and it was noticed that the transport effectively went through Stop in all the combinations tried, even though that lever was not used. Loading and unloading cassettes, cleaning and demagnetizing were all easily performed. The push-button switches were easy to use and completely reliable. I would have preferred a slightly different layout: With Memory to the left under the counter, and the Dolby NR/HX status light near its selector switch. The level meters were easy to use, but would have been more so with thicker needles and less lag between music peak and maximum needle deflection. The instruction manual was in draft form, and the illustrations could not be checked. The text, however, had considerable detail with many pertinent comments with excellent maintenance instructions.

Listening checks were made primarily with record sources, direct discs including Buddy Spicher's Yesterday and Today, dbx-encoded discs such as John Williams' The Empire Strikes Back and others, and pink noise. Most everything sounded very good, although it was possible to hear little subtle losses when using the dbx-encoded discs. Increased noise was one of the changes noted regularly. The results with Type II tapes (CrO2 types) weren't very good--dull at higher levels. The metal tape was excellent at high levels; that was expected.

The surprise was how excellent the ferric tapes sounded at high record levels-a definite contribution from Dolby NR/ HX. Noise from Rec, Pause and Stop was very low in each case, with a little "click" out of tape noise with Stop. The unit generated very little heat, which might be of interest to some users.

The NAD 6040 deck offers excellent responses, even with ferric tapes at Dolby level, low distortion, high signal-to noise ratios, high separation, and peak-responding meters. A good part of such success is due to the successful incorporation of Dolby NR/HX. With a price of $279.00, this deck is certainly a good value, with performance comparable to some decks selling at much higher prices.

-Howard A. Roberson

( Audio magazine, Dec. 1980)

Also see:

NAD 6300 Monitor Series cassette deck (ad, Jan. 1988)

NAD Monitor Series CD player (Feb. 1988)

Link | --Nakamichi Dragon cassette deck (Jul. 1983)

= = = =