Manufacturer's Specifications:

FM Sections:

Usable Sensitivity: Mono, 11.2 dBf.

50-dB Quieting Sensitivity:

Mono, 17.2 dBf; stereo, 38.2 dBf.

S/N: Mono, 90 dB; stereo, 80 dB.

THD (at 1 kHz): Mono, 0.02% in wide mode and 0.08% in narrow mode; stereo, 0.07% in wide mode and 0.3% in narrow mode.

Alternate-Channel Selectivity:

Wide, 60 dB: narrow, 90 dB.

Capture Ratio: Wide, 1.3 dB.

Frequency Response: 30 Hz to 15 kHz. +/- 0.5 dB

AM Suppression: 65 dB.

I.F. Rejection: 100 dB.

Image Rejection: 90 dB.

Spurious-Response Rejection: 100 dB, Subcarrier Rejection: 70 dB.

Output Level: 770 mV at 100% modulation.

Separation (at 1 kHz): Wide, 62 dB; narrow, 55 dB; blend 1, 20 dB: blend 2, 10 dB.

AM Section:

Sensitivity ( Loop Antenna): 300

Selectivity: 50 dB.

Image Rejection: 40 dB.

I.f. Rejection: 60 dB.

S/N: 45 dB.

THD: 0.6%.

Output Level: 250 mV, at 30% modulation.

High-Cut Filter: -6 dB at 10 kHz.

General Specs.

Power Requirements: 120 V, 60 Hz.

Dimensions: 18 1/8 in. W x 3 7/16 in. H x 13 1/2 in. D (46.1 cm x 8.7 cm x 34.4 cm).

Weight: 13.9 lbs. (6.3 kg).

Price: $599.

Company Address: Akai Div. of Mitsubishi, 225 Old New Brunswick Rd., Suite 101, Piscataway, N.J. 08854, USA.

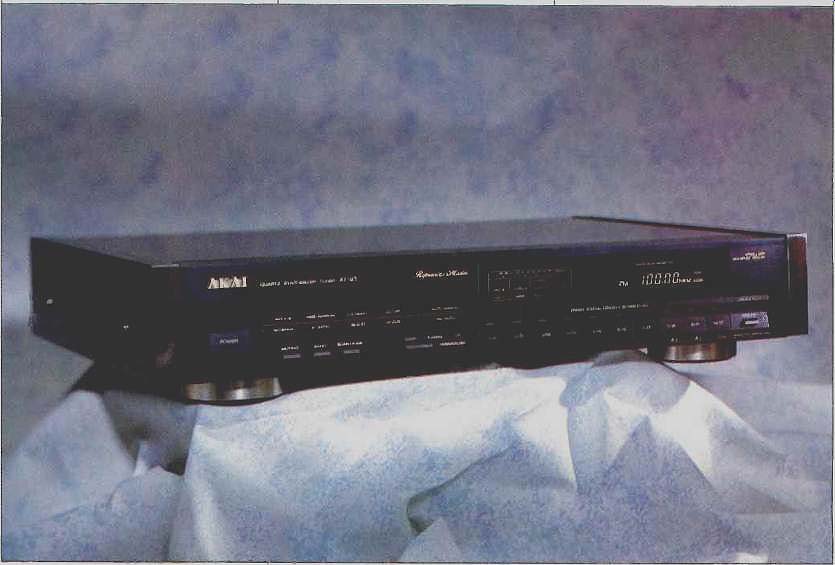

As I began to examine the features of the attractively styled AT-93 AM/FM tuner from Akai, my first reaction was one of moderate resentment. I resent equipment that tries to think for me instead of letting me do things myself. The Akai AT-93 is one of those tuners that decides which of its two antenna inputs provides the best signal, whether it should be in wide or narrow i.f. mode, whether to employ one of its two levels of stereo blend circuitry to reduce noise for weak-signal stereo, and whether to activate its high-cut filter to further reduce noise or other interference. Upon closer examination, and a brief reading of the owner's manual, my resentment quickly turned to admiration. Akai had the good sense to allow a user to defeat those decisions by simply touching any one of several manual-override buttons. Here, at last, was a tuner that offered the best of both worlds:

Optimum automatic operating modes for those who simply want to sit back and listen to the best FM reception avail able, even during rapid DX-ing, and manual selection of all modes for inveterate experimenters and button-pushers.

The Akai tuner has a pair of antenna inputs, each of which can be connected to a separate antenna. For example, you could have two outdoor antennas facing in different directions. The AT-93 employs a comparator circuit that samples the incoming signals and routes the stronger signal to the tuner circuitry when the station is first tuned in.

As mentioned, the microprocessor-equipped AT-93 judges signal quality to determine the best setting for i.f. bandwidth, stereo blend (two levels plus mono), and high-frequency cut. These settings (or your own overriding ones) can be stored in any one of the tuner's 20 memory presets.

There's an unusual feature associated with these, presets:

The Akai has a sequential station-call function for automatic selection of up to three different stations. The desired stations are memorized and then recalled when the tuner is turned on via a timer. This function is extremely useful for absentee recording. If you set the external timer to switch on and off as many as three times, the unit will be tuned to preset 20 the first time, preset 19 the second, and preset 18 the third. In addition to the sequential station-call tuning just described, there are several other ways to tune the AT-93:

You can manually select presets, auto-scan through the presets, auto-scan to the next station up or down, or tune up or down in 0.1-MHz increments.

As for the AT-93's circuitry, it employs a dual-gate MOS-FET in the r.f. stage and a phase-locked-loop, quartz-synthesized tuning system. Separate power-supply circuits are used for the digital and audio sections.

Control Layout

At the left end of the slim, black front panel is the power on/off button. Operating-mode buttons for antenna selection, i.f. bandwidth, blend selection, and high-cut filtering come next. An "FM Auto" button selects automatic or manual FM-reception mode, while touching any of the other four operating buttons restores manual control of the previously automated function. The display area at the upper right of the panel shows tuning information as well as the various modes currently in effect. Pressing a "Preset Scan" button at the far right initiates scanning; pressing the same button the separately supplied AM loop antenna, and a pair of audio output jacks. The 75-ohm coaxial receptacles are not quite the standard F-type used in the U.S. for video and other r.f. applications, but fortunately Akai provides the necessary adaptor so you can connect a standard coaxial transmission line.

Measurements

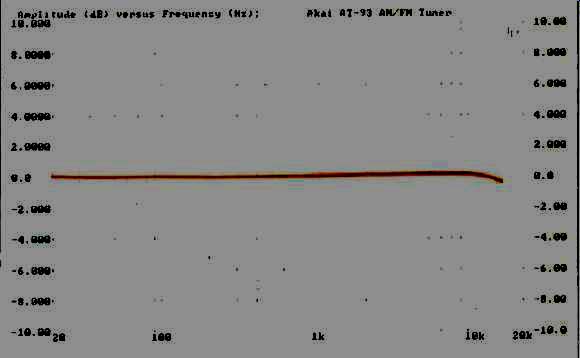

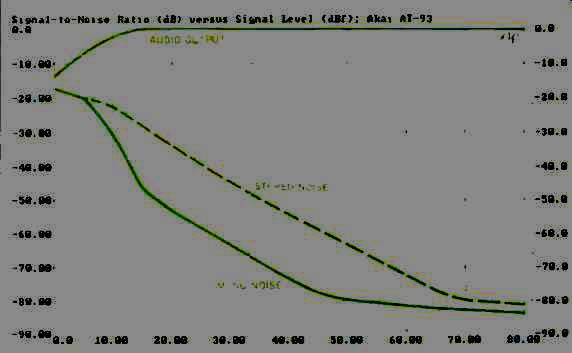

Figure 1 shows the overall FM frequency response of both channels; the two channels were so closely matched that no difference is visible between them. Response was close to ruler-flat from 20 Hz to 13 kHz and was down a mere 0.2 dB at 15 kHz. Usable sensitivity in mono measured just over 12 dBf. The stereo indicator light goes off at about 20 dBf, but stereo reception continues down to about 6 dBf, as shown in Fig. 2, though with diminished separation. Of greater significance was the tuner's excellent quieting characteristics: 50-dB quieting in mono was reached with a signal level of only 16.5 dBf, while for stereo, the signal level required for 50 dB of S/N was 35 dBf. Both figures are better than those claimed by Akai. A full plot of mono and stereo noise characteristics, as a function of signal strength, is shown in Fig. 2. Because results were substantially the same whether I used the narrow or wide i.f. mode, only one set of curves is shown. With strong signals, mono S/N reached 83 dB. At 65 dBf, stereo S/N was 77 dB, but with an even stronger signal of 80 dBf, stereo S/N surpassed the 80-dB mark.

Fig. 1-FM frequency response. Response of the two channels is substantially

the same.

Fig. 2-Mono and stereo quieting characteristics for wide i.f. mode. Results

for the narrow mode were virtually identical.

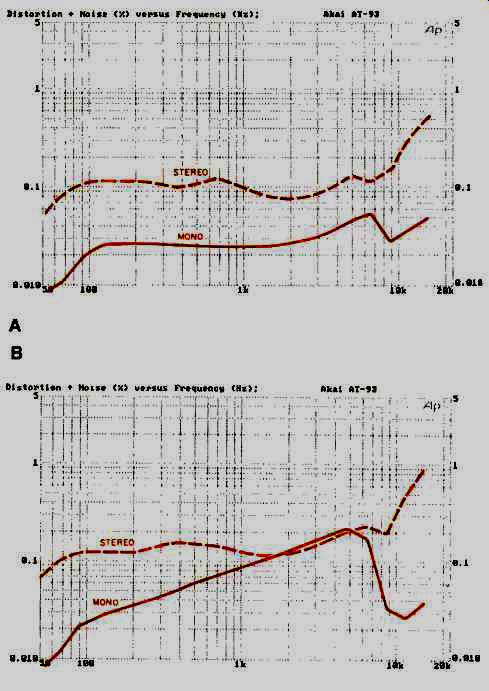

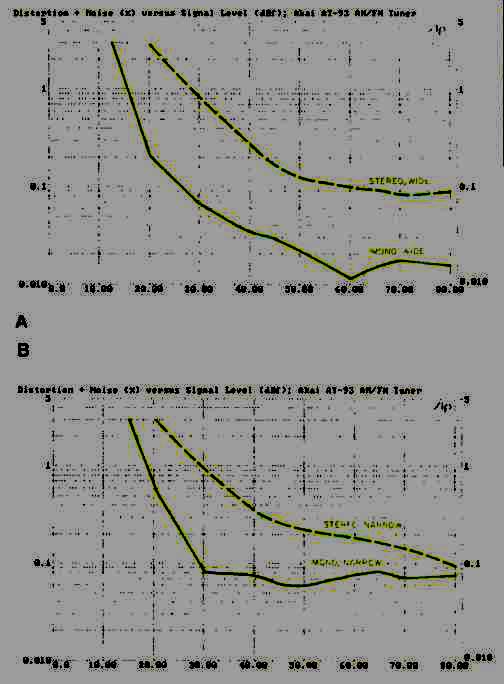

Fig. 3-THD + N vs. frequency for wide (A) and narrow (B) i.f. modes.

Fig. 4-THD + N vs. signal strength for wide (A) and narrow (B) i.f. modes.

Figures 3A and 3B show how THD + N varied with frequency for the wide and narrow i.f. modes. The IHF/EIA Standard for tuner measurement requires that THD be quoted for three frequencies: 100 Hz, 1 kHz, and 6 kHz.

Whenever I make these tests, I use a recommended band pass filter with -3 dB cutoff points at 200 Hz and 15 kHz.

This filter explains the apparent "dip" in THD at the extreme low end of the audio spectrum and the seeming reversal of the curve direction between about 7 and 10 kHz. In any event, at 1 kHz, actual mono THD + N in wide i.f. mode was about the lowest I have ever recorded for any FM tuner: a second time locks in the chosen station. Additional buttons along the lower left edge of the panel select muting, band, and the scanning mode. Next come the up and down manual tuning switches and 10 preset buttons. No "shift" key is needed to make these handle the 20 preset station frequencies; pushing any button twice switches it from the first decade (1 to 10) to the second (11 to 20). Above the preset buttons, appropriate green or red LEDs illuminate to show which decade has been chosen. A "Memory" button at the lower right corner completes the front-panel layout.

The rear panel is equipped with two 75-ohm coaxial antenna connectors, spring-loaded terminals for hooking up 0.025%! In stereo, at 1 kHz, distortion plus noise measured 0.095% in wide mode. The results were almost as impressive at 100 Hz, and at 6 kHz, mono THD + N was only 0.052%; in stereo, it increased to 0.12%. Of course, when I switched to the narrow i.f. mode (Fig. 3B), distortion figures increased, but even then, mono THD + N measured only 0.088% at 1 kHz; in stereo, the reading was 0.13%. I know of several highly regarded tuners which don't do this well even in their widest i.f. bandwidth setting.

Figures 4A and 4B show how THD + N varied as a function of signal strength in mono and stereo. Note that in the wide i.f. mode (Fig. 4A), it took only 26 dBf of signal input to bring distortion down below the 0.1% mark. Even when switching to the narrow mode (Fig. 4B), mono THD + N remained below 0.1% for all signal levels above 28 dBf. In choosing selectivity levels for the i.f. modes, it is clear that Akai did not go overboard in their choice of parameters for the narrow bandwidth. All too many tuner designers, given this multi-bandwidth option, choose to make the narrow setting so narrow that, although its use reduces alternate-and even adjacent-channel interference, distortion often rises to unacceptable levels, negating the advantage of this setting.

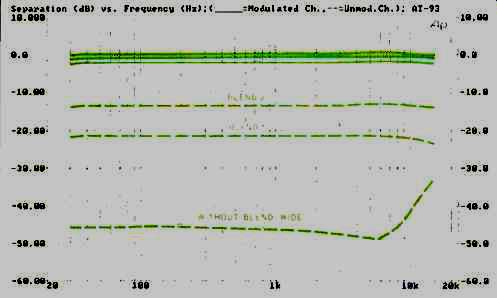

Fig. 5A--Frequency response (top curves) and separation (bottom curves), with

and without blend, for wide i.f. mode at 65-dBf signal level. Response curves

are (top to bottom) without blend, with blend 1, and with blend 2.

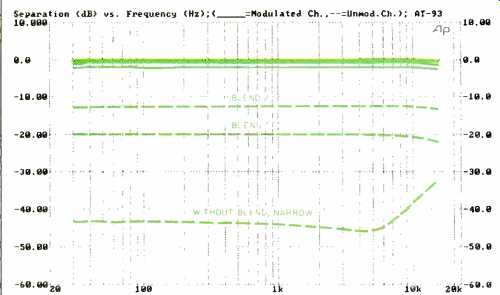

Fig. 5B--Same as Fig. 5A but using narrow i.f. mode.

Fig. 5C--Frequency response (top curves) and separation (bottom curves), without

blend, for four low signal levels in wide i.f. mode.

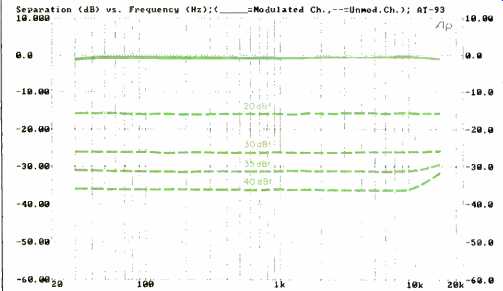

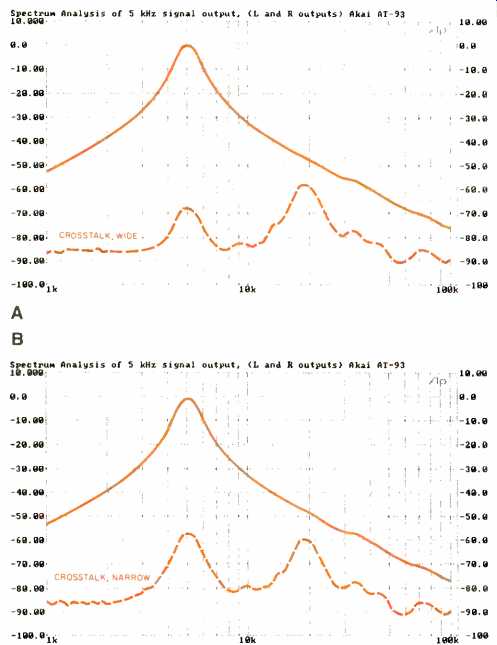

Fig. 6--Separation for a 5-kHz modulating signal (top curve) and crosstalk

components plus subcarrier and sideband components (bottom curve) for wide

(A) and narrow (B) modes.

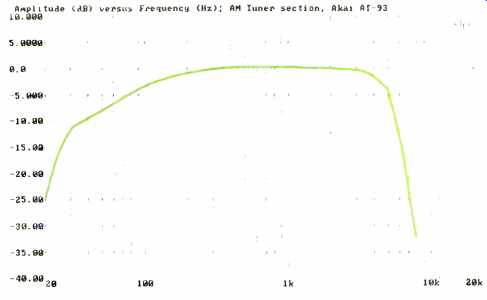

Fig. 7--AM frequency response for signal with NRSC pre-emphasis.

In experimenting with the stereo circuitry, I discovered that in addition to the two available blend settings selectable by the user, weak stereo signals will also result in reduced separation, very much as car FM tuners operate in a semi-stereo mode under weak-signal conditions. The purpose, of course, is to retain some stereo effect while partially reducing the unacceptable background noise levels that other wise would exist. Consequently, I decided to plot three sets of curves to show the AT-93's separation characteristics.

The first set, Fig. 5A, was plotted with the tuner in wide i.f. mode. The bottom curve is the normal separation achieved when no blend setting is used. Separation over most of the audio range was around 47 dB, decreasing to 41 dB at 10 kHz. When blend 1 was selected, separation decreased to about 22 dB; in blend 2 mode, separation decreased still further, to about 13 dB over the entire audio range.

There was a slight difference in output level from the modulated channel as I switched from normal to the two blend positions, which explains the three closely spaced response curves at the top of Fig. 5A. The top solid curve is the referenced output for the normal stereo setting, while the two lower solid curves were obtained for blend 1 and blend 2, respectively.

Figure 5B is the same as Fig. 5A, except the plots were made with the tuner set to the narrow i.f. position. Note that in this mode, separation for normal stereo reception (bottom curve) was very nearly as good as that obtained in the wide setting: About 44 dB at 1 kHz, as opposed to 47 dB in Fig. 5A. Again, this attests to the intelligent choice of bandwidths made by Akai's engineers in designing their i.f. modes. As might be expected, the blend 1 and 2 settings provided almost identical results to those obtained in the wide mode.

Finally, with neither blend setting activated, I reduced signal strength in steps-to 40, 35, 30, and 20 dBf (just above the point where the stereo light goes out)-to obtain the separation curves of Fig. 5C. This time, no level shift of the modulated output (top curves) was observed, but with decreasing signal strength, separation decreased almost linearly, as the tuner gradually shifted from full stereo toward monophonic operation. Even at 20 dBf, however, there was still enough separation-around 16 dB at all frequencies-to render a reasonably good stereo effect.

Figures 6A and 6B are my standard tests showing the output when a 5-kHz signal modulates my FM test generator in stereo. Figure 6A was plotted with the tuner set to the wide i.f. mode, and Fig. 6B was plotted with the tuner set to the narrow mode. Each solid curve (with a peak at 5 kHz) represents the desired output from the left channel, while the dashed curves show separation as well as other distortion and crosstalk products. In both figures, note that the 19-kHz subcarrier product is only about 60 dB below maximum modulation level. In separate spot tests, a 61-dB attenuation of the 19-kHz subcarrier output was observed. I have, of course, measured tuners which exhibit greater suppression of this signal, but the lower amount of attenuation, in this case, is directly related to the excellent response shown earlier in Fig. 1. By not using too sharp a 19-kHz rejection filter and by making sure that the filter did not start attenuating frequencies below 15 kHz, Akai's engineers managed to retain virtually flat response over the entire FM audio frequency range. As for the 60-dB pilot-carrier attenuation, it is really quite enough. Any residual 19-kHz subcarrier product present at the outputs is not likely to affect Dolby tracking when you use the AT-93 to record FM programs. It is also unlikely that you will hear any 19-kHz artifacts when listening to the tuner, even if your ears are as keen as a teenager's.

About the only difference I detected between the results of Figs. 6A and 6B was the slightly reduced separation at 5 kHz in the narrow mode (Fig. 6B).

If you are a careful observer of my graphs, you may be wondering why the apparent separation at 5 kHz in Fig. 6A (68 dB) and Fig. 6B (58 dB) is so much greater than it appears to be in Fig. 5A (48 dB) and Fig. 5B (45 dB). The reason is simple: When I measure separation across the band, the amplitude emanating from the unmodulated channel includes not only the discrete frequency modulating the opposite channel, but the other related signal components (harmonic distortion) and unrelated signal components (subcarrier products, noise, etc.) which are present at that output. In Figs. 6A and 6B, however, the test equipment is behaving much like a spectrum analyzer. Thus, when sweeping through the 5-kHz point, it reads only the 5-kHz component.

Capture ratio, measured only for the wide setting, was 1.2 dB, and i.f. and spurious-response rejection both were in excess of 100 dB. Alternate-channel selectivity was 58 dB in the wide mode and exactly 90 dB in the narrow mode. AM suppression was 63 dB on my sample, and image rejection was 95 dB. SCA rejection measured 59 dB; muting thresh old was set to 39 dBf, a bit higher than I would have liked.

For this and all future tuner reports, I am going to assume that AM stations in most areas have adopted the newly proposed NRSC Pre-Emphasis Standard. (Hundreds of radio stations have reported that they are already using this fixed pre-emphasis.) Accordingly, when I measure AM frequency response from now on, I will be incorporating 75-11S pre-emphasis in the audio sweep signal that is used to modulate my AM test generator. Thus, a tuner designed by engineers who care about AM response will yield a reason ably flat response curve with this test setup. Such was the case with the Akai AT-93's AM section-at least at the high-frequency end of the spectrum. As shown in Fig. 7, response extended out to just above 5 kHz for the-6 dB cutoff point. I'm not quite sure why response rolled off so rapidly at the low end (down 6 dB at around 70 Hz), but that's the curve that it plotted.

As for other AM characteristics, selectivity measured 48 dB (very good for AM), i.f. rejection was 62 dB, and image rejection was 41 dB. Distortion, using a 1-kHz signal at 30% modulation, was 0.5%, while S/N for a 1-mV input signal was 47 dB. Aside from the absence of ultra-low bass response, listening tests conducted for the AM section revealed that it sounded better than most of the AM tuner sections in many name-brand "high-fidelity" tuners and receivers.

Use and Listening Tests

I started auditioning the Akai AT-93 with the unit set to its automatic tuning mode-the one in which the tuner's own microcomputer decides which antenna, i.f. setting, blend mode, and high-frequency cut to use for each received signal. The two antennas employed were my outdoor multi-element antenna and an amplified indoor antenna. For each of the 53 usable signals I was able to pick up, I deliberately reset all of the parameters that the tuner had decided to use, one by one, to see if I could improve on the AT-93's choices. Of the 53 signals received, the tuner switched to mono on five of them because of weak signal strength. I decided that I could tolerate two of those five signals in stereo after all. In every other respect and for every other signal received, I could not outsmart or second-guess this tuner! It always chose the optimum operating parameters.

Although this may have wounded my ego a bit, it sure speaks well for the way the built-in microcomputer decides to program this amazing unit.

Setting up my 20 presets was easy-a lot easier than on some tuners and receivers I've tested. I also tried out the absentee recording capability. While the AT-93 was in my listening room, I had to be away for two days. On both days, two different stations were broadcasting programs I wanted to record. I only had a one-event timer, so I got someone in the lab to manually turn on the tuner for the second event.

Sure enough, the second preset frequency appeared, just as promised. As an FM tuner fan from way back, I was truly astonished by the performance this Akai component delivered-especially since its price is about half that of several tuners I recently tested and listened to that didn't perform as well. If you are looking for the right FM tuner for your system and care about good FM reception, I can recommend the Akai AT-93 without any qualifications or reservations.

-Leonard Feldman

[adapted from AUDIO magazine/Dec 1988]

Also see:

Link | --Carver TX-11 FM Stereo Tuner (Dec. 1982)

Audio Dynamics T-2000E Tuner (Feb. 1989)

[adapted from Audio magazine]