by John Sunier

[John Sunier is the author of three books related to audio, including The Story of Stereo: 1881-. He writes about music and audio for a number of national periodicals, and hosts Audiophile Audition, a weekly radio program carried by 115 public and several commercial stations.]

There's only one way to come close to reproducing human hearing binaural reproduction. This method is so basic and simple that its first use came way back in 1881.

Over the years since stereo be came the norm, various approaches have been tried to carry its spatial realism a step or two further. These have involved both the continuous refinement and improvement of stereo itself (with, perhaps, some temporary backward steps) and the exploration of other approaches.

The best-known of these multi-dimensional alternatives, quadraphonics, failed to win public support. This led, however, to other multi-speaker approaches. Two of these, the Dolby Surround system used in video soft ware and movies, and the Ambisonic system from Britain, resemble the old quadraphonic systems in their use of matrixes which encode four channels of information into two (and, in the case of Ambisonics, the alternative of using four discrete channels). The others either extract ambient information from the main program, which the quad, Ambisonic, and Dolby Surround matrixes can also be used for, or simulate ambience by feeding a delayed version of the main signal through rear or side speakers. The signals from delay systems (and, occasionally, other multi-dimensional add-ons) are sometimes mixed with the main speaker and sent to the front speaker pair, though this can muddy the sound if used too liberally. The aim of all these systems is to increase apparent spatiality.

Another approach is to treat the main signal so as to increase the spatial ambience or localization, or both, available from two stereo speakers. Examples of this include Bob Carver's Sonic Holography and past or present units by Sound Concepts, Omnisonix and Fisher, as well as the Polk SDA speakers and speakers from Imaged Stereo. When properly set up and sensitively employed, some of these units can add a tremendous realism and naturalness to loudspeaker reproduction, but none of them can accurately repro duce the human hearing experience in all its amazing accuracy and versatility. There is only one way to come fairly close to that goal, and it is by using a method of reproduction so basic and simple that its first recorded use came only a few years after the invention of the phonograph--in 1881, to be exact.

It is called binaural reproduction--bi, for two, and aural, for ears.

On August 30 of that year, the German Imperial Patent Office granted a patent to the Parisian engineer Clement Ader, covering "Improvements of Telephone Equipments for Theatres." This was, of course, long before the development of either vacuum tubes or radio, so connections originated with simple telephone transmitters (mouth pieces) and pairs of telephone lines from the stage of the theater to the homes of the telephone subscribers.

Evidently, more than one transmitter was used to feed each of the two phone lines, probably to get enough volume. The transmitters were distributed across the stage in right/left pairs, and the subscribers listened via separate phone earpieces at each ear one for the left phone line and one for the right. Ader's patent states: "Thus the listener is able to follow the variations in intensity and intonation corresponding to the movements of the actors on the stage. This 'double listening' to sound, received and transmitted by two different sets of apparatus, produces the same effects on the ear that the stereoscope produces on the eye." Ader was quite aware of what he was doing, and he did not hit upon his arrangement merely by chance; his patent drawings substantiate this. His device received much attention during the 1881 Paris Exposition, when it was used to broadcast live presentations direct from the stage of the Paris Opera. A similar setup was installed by an inventor named Ohnesorge in the mu- sic hall of the Crown Prince of Prussia.

Later in the 19th century, a commercial venture based on this approach was marketed under the name Steidel's Stereophony.

----- The advantage of using mikes on a dummy head is that, by modifying the sound field just as human features would, conditions of human hearing are nearly duplicated.-----

---At the 1933 Century of Progress Exhibition, audience members listened through binaural telephone receivers while demonstrators addressed "Oscar" (back to camera), a tailor's dummy with a sensitive microphone implanted in each cheekbone.

How Binaural Works

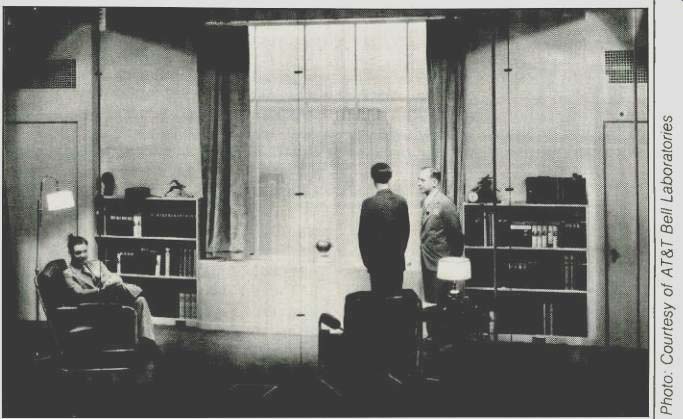

The analogy of binaural hearing to stereo seeing has often been made (Fig. 1). Though in its finer points there are some sizable differences, the analogy makes the whole function of binaural reproduction more understandable.

Fig. 1--Our two eyes (A) and our two ears (B) work with our brain in analogous,

though not identical, ways to capture three-dimensional images. (After: The

Story of Stereo: 1881-, by John Sunier.)

The workings of the brain are responsible for both of these physiological phenomena. The brain takes the two very similar but also very slightly different signals, whether they be optic nerve impulses or impulses from the inner ear, and processes them instantly to give us depth of image or depth of sound.

Early in man's evolution, this increased accuracy of perception meant the difference between life and death.

The poor fellow deaf in one ear or blind in one eye had had it-no getting away from that saber-toothed tiger! Our senses have probably been dulled over the eons, but listening to binaurally recorded or broadcast material can make one aware of just how specific our hearing can be. We have some sense of spatial location when listening to well-done stereo recordings through properly set-up speakers, but this is only a pale imitation of binaural, which allows one to locate sounds not only horizontally but also vertically--actually 360° in every direction.

In binaural, there is a lack of accurate location when the sound source is directly above, ahead or to the rear.

But if you close your eyes and have a friend click fingers directly in front of, above, and behind you, you will discover this problem is inherent in the hearing apparatus, not in the binaural approach! It is very difficult to tell if the sound is in front or behind, unless it moves to that point from the sides.

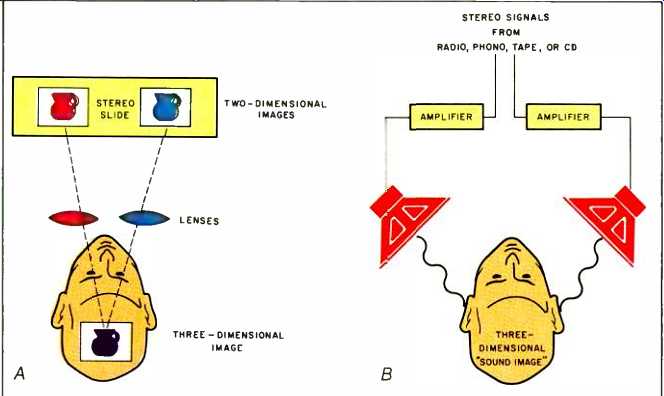

So just what, exactly, is a binaural microphone setup? Well, it can be as simple as two omnidirectional mikes spaced on a stand about 7 inches apart to simulate the separation of the human ears. The left mike signal is kept totally separated from the right signal through the entire system. One can record in any stereo tape format, though the greater the signal-to-noise ratio, the better will be the binaural effect. Hiss can be very noticeable with stereo headphones, as most of us are aware, and there are few other sounds leaking in (even with open-air head phones) to mask any of the noise in the recording. Further, with binaural, some extremely low-level and subtle sounds can be clearly heard by the listener, and it is vital not to have such delicate sounds obscured by the high noise floor of most analog recording methods. PCM digital recording is therefore the perfect medium for binaural reproduction. The other alternatives, if digital equipment is not available, would be cassette recording with dbx NR encoding or, as a second choice, with Dolby C NR encoding. The best-quality metal-particle cassette tape should be used, and one shouldn't be concerned if the recording levels seldom hit peaks, because few sounds will be close to the mikes.

A simple improvement to the spaced-mikes approach is to mount a piece of quarter-inch plywood, about 4 by 6 inches in size, exactly between the two mikes to act as a head shadow--a baffle which simulates the acoustic effect of the human head.

This is also sometimes called a septum. You can refine it even further by covering the board with a layer of felt (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2--A binaural microphone setup using a baffle to simulate the acoustic

effect of the human head.

As you can see, the equipment required for binaural recording and listening is probably already available to you. No special encoders or decoders or processors are needed--just two clean channels of recording and reproduction ending in a pair of good stereo headphones. The better the head phones, the better the results will be; I prefer good electrostatics, but the effect will be startling with almost any type. Also, the mikes need not be the most expensive. While better mikes give better results, the general binaural effect will come through well with the most basic equipment.

Another advantage to doing your own binaural recording is the ease of mike placement. Just listen through headphones to the signal from the mikes as you move them to several locations; the location that sounds best is obviously the one to use. The binaural method is extremely forgiving of mike setup. No musicians will ever be "off-mike," because you are not trying to bring the musicians into your listening room--you are going to the concert hall or studio! Similarly, you may find that audience noises that would be extremely annoying with ordinary stereo just become part of the "in person" concert-hall experience and actually add to the realism.

Dummy Heads and Live Heads

If you would like to go all the way with binaural recording, you can use a "dummy head." The first appearance of such a head was, in fact, the most publicized experiment with two-channel reproduction (until the advent of stereo recording in the 1950s). In the winter of 1932, a wooden tailor's dummy, named Oscar by some Bell Laboratories engineers, took up residence at the American Academy of Music in Philadelphia. He was part of a project in which Leopold Stokowski, always interested in improving music reproduction and recording, took part. (This project also made some of the first experimental stereo recordings, using basically the same 45/45 cutting system as today's stereo discs.) Oscar had sensitive microphones as sensitive as they had in 1932, that is-implanted in his cheekbones in front of his ears. These were used to pick up Stokowski's Philadelphia Orchestra; a monaural pickup was also made, alongside. Visitors to the American Academy were asked to listen in another hall, using headphones, and to note any preference between the full-range mono sound and a filtered, limited-range binaural signal via Oscar. They all preferred the binaural reproduction, even when all frequencies over 2.8 kHz were cut off. Oscar then travelled to the Century of Progress Exhibition in Chicago, where he continued to amaze visitors. They listened through headphones while looking at people, at some distance, who moved around Oscar while speaking or making sounds. (In another part of this exhibit, the public was tested for hearing sensitivity at various frequencies and sound levels; this eventually yielded the parameters for the Fletcher-Munson loudness curve.) The advantages of the dummy head over unadorned spaced microphones were noted by the Bell engineers. By modifying the sound field near the two mikes, just as human features modify the sound we hear, the conditions of human hearing were duplicated as closely as possible. During later experimental work in Germany, as mikes of smaller size were developed by Bruel & Kjaer and others, they were placed deep inside dummy heads, where eardrums would be on a human head, at the ends of ear canals. The effect was startling, but unnatural, be cause the sound had to pass through two sets of ear canals-the dummy head's, during recording, and the listener's, during playback. In spite of this, such an end-of-the-ear-canal dummy head is still used in some bin aural work, together with special equalization to correct the problem.

Even finer adjustments can improve the realism of the binaural dummy head, also called Kunstkopf ("art-head") stereo by the Germans. The makers of Mercedes cars use a Kunstkopf, together with a Sony PCM-F1 digital processor and Stax headphones, to record interior car noises for test purposes. Mercedes' demands for better low-bass reproduction via head phones led Stax to develop their top-of-the-line earspeakers. The Mercedes engineers also found that including shoulders and even hair on their dummy head improved the realism and ac curacy of the binaural pickup. Their latest head, with tiny B & K mikes buried at the ends of the ear canals, has also been used experimentally for some state-of-the-art binaural concert recordings in a German cathedral.

If you want to use a dummy head for binaural recording, Neumann makes one, the KU 81, complete with their condenser mikes mounted inside, but it is not inexpensive. Sennheiser also sells a head, dubbed Fritz. Another possibility is to find a foam wig head and make your own. Hollow out a space at the center of each ear large enough to accommodate a small tie-clip condenser electret mike such as the Sony ECM-16T. If you already have a pair of good omnidirectional mikes, you can hollow out just enough indentation near the ears to lay the mikes as close as possible to the sides of the head. Face them straight up or for ward, and remove any wind screens to allow closer proximity to the foam head. If the head will sit by itself, the mikes can be held in place by rubber bands. Add a wig, and if the head lacks a nose, attach a putty one or glue a small baffle in the proper place, because even this has an effect. You might also try two pieces of foam tape curved into a "C" shape if the ears of the head are not prominent.

In the Air and On the Air

To return to binaural's history, the process was used in both World Wars.

In World War I, binaural receiving trumpets were used to locate enemy war planes (Fig. 3). They were spaced several feet apart to increase location acuity, and were connected via rubber tubing to the two ears of an operator.

Similar devices known as geophones were used to determine the direction of underground sounds such as enemy trenching operations. In World War II, underwater binaural pickups were made with hydrophones to help detect enemy submarines.

In the March 1924 Journal of the AIEE, an article titled "High Quality Transmission and Reproduction of Speech and Music" appeared. Its authors, W. H. Martin and Harvey Fletcher, had some prophetic things to say about two-channel broadcasting: "With binaural audition, it is possible to concentrate on one sound source and to disregard other sounds coming from different directions or distances. Be cause of the monaural character of broadcasting, it is necessary to go even further in reducing noises and reverberation at the transmitter than would be the case for an observer using two ears at the same location. . . .

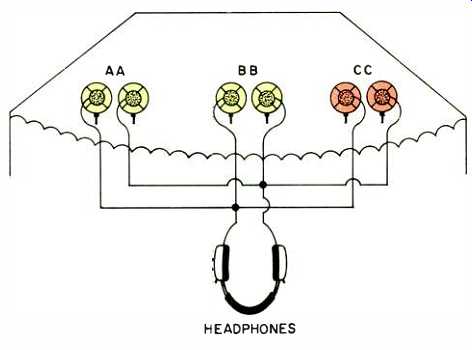

In broadcasting, those who make use of the system are becoming more critical of the service which it renders and the quality of reproduction will be of increasing importance in the future." In the following year an inventor named Kapeller developed an improvement on the early Ader system of 1881. He mounted six microphones, spaced as three pairs the same distance apart as human ears, at the edge of the stage of the Berlin Opera House (Fig. 4). The left mikes of each pair were connected to one set of cables and the right mikes to a second set. Realizing the difficulties in supplying two separate cables to each listener's home, Kapeller saw the possibility of using radio broadcast. He cited the example already set by a Berlin radio station which had experimentally carried out two-channel broadcasts using two transmitters, at wavelengths of 430 and 505 meters.

In that same year, 1925, a U.S. radio station, WPAJ in New Haven, Connecticut, was experimenting with binaural broadcasting. An additional wavelength of 1,110 kHz was added to their original frequency of 1,320 kHz, and duplicate transmitters were installed (Fig. 5). Two standard broadcast mikes of the time were used, one to each channel, with a 7-inch separation. Ordinary reception was not impaired, since basically the same program was heard on each wavelength. Binaural listeners used one radio set tuned to 1,320 kHz feeding a single earphone on the left ear, and a second radio set tuned to 1,110 kHz feeding a single earphone on the right ear. At this time, loudspeakers were just beginning to come into use for radio listening. It was found that the speakers mixed up the sound from the two discrete channels and seriously impaired the binaural effect.

The WPAJ work was described by engineer F. M. Doolittle in Electrical World magazine. The station used a single transmitting antenna for the two frequencies, and the two home radios could also be operated from a single antenna. The experimenters found that an impression of greater depth and more distance between listener and performer was gained if the mikes were moved somewhat further apart than 7 inches. But if they were moved too far apart, the binaural impression became vague and was eventually lost altogether. It was also found that bin aural transmission produced an apparent increase in volume.

Doolittle showed his understanding of the binaural effect very clearly in his article: "The phonograph and the radio have educated the ear to believe that a close approximation to true tone values is really all that can be expected, and hence the listener does not expect an exact reproduction. Reproduction, using the word in its strict sense, would, of course, mean a rendition so nearly identical with the original that one would be unable to tell, without bringing into play other faculties than that of hearing, whether or not he is present at, and listening to, the original performance. A close approximation to such reproduction is possible with [this] method. . . ."

A few American radio stations con ducted similar experimental binaural broadcasts at this time, but radio was still in its infancy and not many people owned the two sets necessary for listening to the broadcasts. So the pioneering work of WPAJ was almost for gotten until the FM-plus-AM stereo broadcasts of the late 1950s, most of which were not binaural.

Binaural's Modern History

Audio's own Bert Whyte brought bin aural recording out of the attic for a while in 1950. During his employment with the Magnecord tape recorder company, General Motors requested help in recording and analyzing the specific locations of car noises. Whyte recalled the Oscar demonstrations of 1933 and assembled two Telefunken U-47 omnidirectional mikes on a stand separated by a quarter-inch slab of wood for a baffle.

Two-channel tape heads were not yet available, so the simplest way to record and play back two separate signals was to modify a monophonic three-head assembly to include a full-track erase head, a normal half-track monophonic record/play head where the record head was normally mounted, and a second half-track record/ play head, inverted to scan the normally unused half of the tape, in the position of a normal playback head.

(Editor's Note: Magnecord heads of the time had removable pole pieces, which made such gap inversions easy.- I.B.)

This staggered-head arrangement, with the heads 1 1/4 inches apart, worked fine, according to Whyte. It became a temporary standard for two-channel recording, with a few decks and prerecorded tapes available in this format, until stacked-gap stereo heads became available a year or two later.

(Editor's Note: By 1955, some companies were issuing two-channel tapes in both staggered and stacked formats, but primarily for stereo [loudspeaker] rather than bin aural [headphone] listening.-I.B.)

When stereo tapes were first issued to the public by Livingston, and double-groove stereo LPs (played with a forked arm holding two cartridges) by Cook Laboratories, they were erroneously called binaural, though they were actually stereo. This caused some con fusion later on.

------Binaural isn't 100% accurate; problems remain with frontal and direct-rear locating. For example, dead-ahead sounds may seem to be elevated or to come from behind.------

Fig. 3--Binaural listening apparatus was used in World War I to locate one

my airplanes before the invention of radar. (After Sunier.)

Fig. 4--The binaural pickup system used at the Berlin Opera House in 1925.

(After Sunier.)

Fig. 5--The binaural broadcasting setup used by New Haven radio station

WPAJ in a 1925 experiment. (After Sunier.)

A second request for a way to use tape recording to localize sounds came to Magnecord from the Navy's Special Devices Center in Sands Point, New York. The Navy was provided with equipment similar to that provided General Motors, and used it for under water work. The headphones of the time were very primitive, with a narrow frequency range, but the binaural results were still astounding.

It occurred to Whyte that it might be interesting to record music with the Magnecord binaural equipment, so he took it to a local high-school band con cert. When these tapes were played in binaural demonstrations at the 1950 New York Audio Fair, listeners were amazed by the results. Later, Whyte began taping professional musicians binaurally. First he recorded Benny Goodman, Stan Kenton and others, in formally, at a Chicago jazz club. Some time after, Whyte went on tour for six months with conductor and sound buff Leopold Stokowski, making binaural tapes of him conducting various college orchestras.

With the advent of stereo, which could be enjoyed by many listeners at once without the encumbrance of headphones, binaural recording attracted less interest. It has never faded out completely, however. In Germany, for example, Sennheiser's 1968 introduction of the classic HD 414 open-air headphones, which weighed only 4 1/2 ounces, and the swift introduction of open-air headphones by Beyer, AKG and others, brought new popularity to headphone listening. This, in turn, stimulated a renewed interest in binaural in that country.

Attempts to produce quadraphonic sound, beginning about 1970, also spurred interest in capturing a more realistic sound field than was possible with two-channel loudspeaker approaches. Binaural was a natural avenue to this goal, and it was much less equipment-intensive than quadraphonic. In the notes to Sennheiser's series of 7-inch, 45-rpm Kunstkopf-Stereofonie demonstration discs of 1973, the following was addressed to head phone listeners: "In these times of superlatives regarding technical achievements, it is still often believed that only high expense can offer better results.

. . . If this documentary disc provides better results at lower cost, why shouldn't it be worthy of such advancement as, for instance, the much-disputed quadraphonic sound?" Sennheiser went on to point out that quad could establish spatial location of sounds in a horizontal plane, but not with great accuracy, and that it had no abilities at all in the vertical plane.

At the 1973 International Radio Exhibition in Berlin, Sennheiser introduced their MKE 2002 "head-bound" stereo microphone. This consumer version of the professional binaural Kunstkopf system mounted the microphones like a pair of stethoscope-style head phones, allowing the recordist to substitute his own head for the dummy head. A few years later, JVC offered a binaural headphone/microphone combination, the HM-200E (now discontinued), and Sony now offers a similar system, the ERW-70C.

However, live heads, unlike dummy ones, are not perfectly stationary.

When a recordist wearing binaural microphones moves his head to one side, the effect, to binaural listeners, is as if the auditorium were swinging in the opposite direction, as sounds formerly coming from dead ahead shift to one side.

The three demo 45s from Sennheiser (no longer available) were recorded in various natural environments, primarily with the MKE 2002 mike system placed on someone's head. The discs included warnings that only Sennheiser's own open-air headphones should be used, for best results. One disc was recorded in an ordinary living room; the narrator explained where he was moving in the room and what he was doing. Another featured sounds of everyday life, such as someone using a phone booth and a scene at a swimming pool. A train station scene began in a way that used one of binaural's unusual features to the utmost: A man and a woman are meeting as a train arrives. They are first heard, one on each side of the listener, as they shout to each other across the crowd. They approach one another until they are slightly behind the listener's position.

The intriguing point here is that the man is speaking German and the woman English, yet the listener can easily pay attention to whichever one he wishes! With ordinary stereo, listening to this exchange would be extremely frustrating.

Another of the demo discs contains an imaginative little sci-fi playlet called "The Exploration of Simeon 2"; unfortunately for most of us, this one is entirely in German. There are also musical impressions in which the listener is entirely surrounded by the musicians, and a rendition of "Windmills of Your Mind" in which the female vocalist moves around the listener.

The Japanese audiophile community also showed an interest in binaural re production in the '70s. A number of binaural LPs were issued, including one, titled "Adventure in Binaural," which opened with a lengthy binaural sound-effects extravaganza re-creating the Battle of Midway. (A rather strange choice, since this was the battle which turned the tide of World War II, in the Pacific, against Japan!) There was also a jazz piano album featuring Junior Mance, recorded binaurally in New York City at a club which had exceptionally noisy patrons, considering that a recording session was under way. However, one hardly minds when listening in this amazing format--it rather adds to the feeling of sitting at a tiny table right in the middle of that smoke-filled club!

---------

top: Fritz II, the Neumann dummy head used to record the radio series

The Cabinet of Dr. Fritz.

above: The Sennheiser MKE 2002 binaural microphone system was worn like a stethoscope, with the wearer's head serving the same function as a dummy head.

above: These prototype JVC headphones included a second pair of drivers in front of the listener's ears to enhance frontal localization.

-------------

Imperfections and Solutions

As already mentioned, the binaural method is not 100% accurate in all of its parameters, nor is it completely compatible with loudspeaker listening-in mono or stereo. Even with headphones, there are difficulties in frontal, overhead, and direct-rear locating. When a marching band, say, passes in a straight line in front of the dummy recording head, it will seem to the headphone listener to have marched in an arc, getting farther away as it moves directly in front of the listener, then getting closer as it continues moving to the other side. Sounds recorded in a circle around the dummy head seem to surround the listener in an oval, and many listeners feel that the entire sound field has moved be hind them. Sound sources dead ahead may also seem elevated above their true positions, or be perceived as occurring to the rear instead of in front.

Some of this is thought to be due to differences between the characteristics of the dummy head and those of the human listener, as well as the transmission characteristics of the stereo headphones used. These difficulties in locating sounds in some positions seem to indicate that the ear and brain sometimes need just a bit more data to process things properly.

Misaligned tape heads in recording, playback, or tape duplication can also cause problems with binaural. A slight misalignment whose effects might be unnoticed with ordinary stereo can seriously degrade the binaural phasing information. The problem does not occur with digital, however.

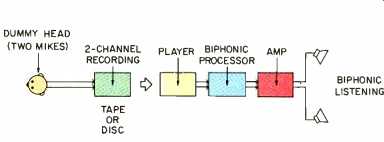

Fig. 6--JVC's Biphonic system electronically processed binaurally recorded

signals for use with loudspeakers.

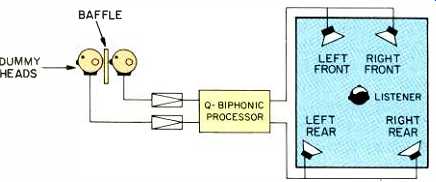

Fig. 7--The JVC Q-Biphonic system used two dummy heads in tandem to pick

up four signal channels, then processed the signals for quadraphonic listening

through loudspeakers.

In an attempt to make binaural recordings compatible with loudspeaker listening, JVC developed their Biphonic system. Sound recorded by a single dummy head is fed into a processing unit, producing a 180° sound-field wrap around the speakers (Fig. 6). The processor electronically "eliminates the spatial crosstalk that is a normal result of loudspeaker reproduction," according to JVC.

Because this system provides localization in the forward direction only, JVC undertook further research into sound-locating techniques. In one test, they placed a dummy head in an anechoic chamber, with a noise genera tor feeding speakers at five points in an arc from directly in front of the head, to straight overhead, to directly behind the head. Listeners monitored these signals via pairs of speakers arranged at various points around the room. It soon became clear, not surprisingly, that unambiguous determination of sounds located front or rear depended on the relative positioning of the reproducing loudspeakers. Four speakers were felt to be necessary to include rearward sound sources.

This led to the development of the Q Biphonic system, using four speakers surrounding the listener, and a double binaural pickup system. This system employs two dummy heads, both facing forward towards the primary sounds, one about 8 to 10 inches in front of the other (Fig. 7). A baffle is mounted between them, similar to the baffle often used in place of a dummy head. Each head produces a pair of binaural signals which are fed to a special processing unit. The processor uses complex equalization and time delay to produce two pairs of signals suitable for presentation through loud speakers rather than headphones. The processing, in effect, produces a binaural-to-stereo transformation.

This system is said to correct some of the problems of both binaural and quad reproduction. It greatly stabilizes both front and rear localization, compared to ordinary binaural. It also can create very convincing side images within the normal quad speaker array of two in front and two in the rear, producing a 360° sound field around the listener. Side images have been a problem for ordinary quad reproduction. Another improvement is the accurate re-creation of sounds very close to the head, next to impossible with a standard four-speaker setup.

The system is not without some drawbacks, as expected. Since the processed sound must be totally free of relative phase shift, the various quad matrix systems such as SQ, QS and UHJ (Ambisonics) cannot be used.

The all-pass networks which are part of these circuits would damage the re created sound field around listeners. A discrete four-channel reproduction system (possible with the Compact Disc!) is the only answer.

In the JVC Q-Biphonic system, the listening position is also restricted to a very narrow area along the axis of left-right symmetry in the loudspeaker set up. The spatial phasors which are responsible for dimensional realism can not be accurately re-created over a wide lateral range. Listeners positioned outside of this narrow range will hear quadraphonic reproduction as it is normally perceived.

Finally, JVC introduced a special Q Biphonic processor which, when fed by multi-track studio recordings which had not been made with binaural microphone techniques, electronically produced Q-Biphonic signals equivalent to those from the dual dummy heads. The distance and direction of sound images could be controlled over a 360° field with a control similar to a conventional pan-pot. But no more has been heard of the Biphonic systems; they seem to have gone down the tubes with consumer quadraphony.

Single-Ear Binaural: The Holophonic Approach

The newest, and perhaps most controversial, multi-dimensional system is Holophonics. The story of its concept has been told elsewhere, but for those who missed it, we'll tell it again: Once upon a time, Hugo Zuccarelli was lying in bed, with one ear buried in the pillow. Someone walked through the room, and Zuccarelli realized that, even though one ear was closed off, he was still able to hear which direction that person was coming from.

The observation of this young physiologist/audio engineer led him to question the conventional theory that human beings locate sounds by calculating, in the brain, the difference in time it takes for sound to reach each ear.

Zuccarelli studied how the brain perceives sound, rather than how the ears receive it. This laid the foundation for the trademarked Holophonic recording system, which Zuccarelli feels is an approach totally different from binaural. In fact, Zuccarelli Communications in Los Angeles and Holophonics Inter national in London don't want to be associated with binaural.

Zuccarelli's mind-bending hypothesis is that the ears independently generate their own sound! He proposes that the ear's own reference beam (he calls it "reference silence") is responsible for generating the spatial information that is an integral part of the human hearing process. The complex interference pattern caused by external sounds coming in contact with this reference beam adds the dimensions of space and time to the hearing experience, he theorizes.

Zuccarelli used a digital recording system in his experiments. He taped various sounds accompanied by a spectrum of almost inaudible tones as artificial reference beams. Finally he found the combination of tones that duplicated those he felt were produced by the ear.

With this critical information, Zuccarelli developed electronic equipment that generates a synthesis of the ear's "reference silence," and which re cords on tape the interference pattern between that synthesis and other external sounds. During playback of recordings made Holophonically, the brain provides a second reference beam, bringing to light the original ambient sounds in their full realism.

The Holophonic recording system, which consists of a transducer and a great deal of associated electronics, is being marketed to the entertainment industry. One disturbing aspect to me is the secrecy regarding what the transducer really is. At recording sessions, Ringo, as Zuccarelli has named the transducer, is always covered up with a fabric bag. Also disturbing to me is the claim regarding Holophonics' ability to be perceived on any play back equipment-high or low quality, stereo or mono.

The Holophonics promoters argue that this capability comes about because the system does not depend on any sort of electronic decoding system for its effect. Recordings encoded Holophonically are said to be decoded directly by the brain. As a result, the promoters claim, even the tiny speaker of a monaural TV set can deliver all of the information the brain requires to "hear" Holophonically. Some listeners detect some added spatial information in Holophonic tapes played monophonically, but to others, they sound exactly like any signal played through a mono speaker. Proponents admit that single-driver speakers do a better job than multiple-driver systems and that, in a four-speaker auto installation, the two rear speakers should be turned off for best results.

The Return of Binaural Broadcast

A fascinating series of binaural radio dramas has been airing on many public and college radio stations for some time now, and, like many series, it will likely be repeated on one of your local stations. Titled The Cabinet of Dr. Fritz, the series of half-hour dramas produced by ZBS Media grew out of an experimental Halloween binaural broadcast of a scary play, entitled "Sticks," in 1982.

Producers Tom Lopez and a woman who goes only by the name of Phoenix used the Neumann KU 81 hard-rubber Kunstkopf, and did original digital re cording with a Sony PCM-F1 unit and portable Beta VCR. They nicknamed the head Fritz II, hence the name of the program series. Some of the original recording was done on location, since the entire recording system is portable.

For a scene in a car, for example, recordist Bob Bielecki got into the car with the actors, the dummy head, and the Sony system. The original digital recordings were dubbed to multi-track analog, using dbx noise reduction for the studio effects and music that were added.

The best production in this series of radio dramas, all of which have a bit of the macabre about them, is the first one-Stephen King's "The Mist," which features 35 actors and is de scribed as one of the most detailed radio dramas ever produced. Monsters were created by putting various live animal sounds into the computer of a Synclavier II digital synthesizer and then playing them on its keyboard. The meow of a Siamese cat became the sound of spiders the size of large dogs, which dropped down on the unsuspecting listener from directly above. The chirp of a parakeet was turned into the shriek of a pterodactyl.

"The Mist," when heard in the proper setting (at night, in the dark) with good stereo headphones, can be much more scary than a motion picture of a Stephen King story. It ran over three of the programs in the series, for a total of 90 minutes-the same as a feature film, interestingly enough.

The other excellent use of binaural in the radio drama series was the story "Aura," by Latin American author Car los Fuentes. A young man answers an advertisement and is slowly drawn into the lives of a strange old woman and her stranger niece, while losing control of his own life.

If Dr. Fritz is not aired in your area, or if you wish to bypass the vagaries of FM transmitters and reception--which can sometimes degrade the binaural effect--you can order either of these dramas on chrome cassettes with Dolby B NR, duplicated in real time, directly from ZBS Media, Box 1201, Fort Edward, N.Y. 12828, (518) 695 6406. Be sure, when you sit down to listen, you warn others in the house that they may hear some disturbing sounds coming from you when those gurgling giant spiders come creeping up from behind!

Tickets for Binaural

Another binaural event that may be both seen and heard if it plays in your area is the brainchild of a Seattle composer with a rather bizarre bent, Nor man Durkee. He calls himself and some of his performances "The Binaural Man." Each seat in the theater where he appears is equipped with a pair of Sennheiser HD 40 headphones connected directly to Durkee for his combination live and digitally pre recorded binaural performance/broad cast. There is no such thing as a bad seat or poor-sounding auditorium when Durkee performs his seriocomic bits, which were described by one critic as a combination of Laurie Ander son, Charles Addams and Hunter Thompson. His performances are something like an audio equivalent of 3-D movies, in that they require the audience to wear special equipment and endeavor to put the audience into the entertainment. However, Durkee is also an artist and an extremely versa tile composer and keyboardist/synthesist. His two different "Binaural Man" programs have toured Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, New York, and Milwaukee.

Durkee's latest project is the world's first binaural opera, which premiered early last year in Seattle and will eventually tour the country. (It will play to audiences limited to 200, since that is all the headphones Durkee has at the moment.) "Oxymora" is based on the diaries of Japanese court ladies of the feudal period of ancient Japan. Durkee wrote the script and music, and his wife Louise created the choreography.

Also featured is the sound of the Kurzweil 250, said to be the first electronic musical instrument that can re-create the sound quality and dynamic range of any acoustic instrument. It was used to create the prerecorded orchestral parts for the opera.

Excerpts of all three of Durkee's bin aural projects are available on cassette on a limited basis. He can be contacted at the International Binaural Institute, Box 45575, University Station, Seattle, Wash. 98145.

Comparing "The Binaural Man" to a 3-D movie brings us to the next place where binaural sound can soon be experienced along with visual entertainment. Since the second wave of 3-D motion picture efforts seems to have run its gimmicky course, one production company has taken a hard look at what other audience-involving format could lure a public that is being lost to video. They chose binaural sound.

The firm's name is Optimax III, and they call their binaural soundtrack system Sonimax. They see it as a total dimensional sound-reproduction system for motion pictures and television.

By utilizing individual stereo headsets, viewers of the feature films will be able to localize the positions of each sound exactly, to experience the illusion of actually being there.

To avoid the immense problems of wiring hundreds of stereo head phones, Sonimax employs Walkman-type FM radios to feed the head phones and a two-channel FM signal broadcast inside the otherwise silent movie theater. Audience members may bring their own FM receivers or rent "designed-for-viewing" receivers and headphones at each theater.

The Optimax III people are keeping very quiet about the exact nature of the proprietary transducer used to pick up the binaural sound during shooting; in photographs I have seen, the equipment at the end of the mike boom is , blacked out. Three feature films are said to be in current production using the binaural Sonimax process.

Optimax's initial brochure seems to have missed one advantage of the pro cess that is really something to tout:

Even without the binaural feature, this system will be pure bliss to serious filmgoers who are being gradually driven out of the movie theaters by those who seem to think they can freely talk to their friends, out loud, as though they were in their own living rooms! For those who want to hear the soundtrack, headphones would be welcome.

Binaural in Your Home

Finally, another opportunity to hear binaural sound, and at no cost, is offered occasionally by the weekly pro gram on National Public Radio which I myself produce, Audiophile Audition.

This hour-long program, which features audiophile recordings in all for mats and short interviews with audio and music personalities, aired several all-binaural programs during its four' years of local San Francisco-area broadcasts. The new national series of Audiophile Audition aired an all-binaural program on May 12, 1985, and again last December 15. The series is carried by many NPR stations (115, by March 1986) and a few commercial concert stations. Most of these stations air it live at 2 p.m. EST on Sundays; check your local radio listings for the exact time in your location, since some stations tape-delay the broadcasts, using PCM digital equipment. Excerpts from most of the binaural projects discussed in this article are featured on the special binaural versions of Audiophile Audition. This format always brings in the greatest amount of listener mail, demonstrating there is definite public interest in this unique method of reproducing sound.

It is unfortunate that almost no commercial binaural recordings are currently available. This writer has urged several record labels to consider a bin aural sampler, but the only current one is a demo CD from Sennheiser, containing a sci-fi drama--in German. (It's also the only binaural CD that I'm aware of, but apparently it's not avail able in the U.S.) The only presently available binaural material, in addition to that already mentioned, are three recordings: The Holophonics group has produced an extremely clever and enjoyable little demo cassette titled Touch the Future. On one side, it contains a sound-effects tour de force integrated into a story concerning some robots and their programmer. On the other side are two selections of music that feature instrumental surround effects not only in a horizontal plane but also in a vertical one, up the wall in front of the listener. It is on chrome tape with Dolby B noise reduction, and is available in the U.S. for about $10 at participating Alpine and Luxman audio dealers.

The other binaural recordings were made back in the heyday of direct-disc in the mid-'70s. Sonic Arts Corp. in San Francisco has two binaural albums which may be unique in also being direct-to-disc. The first presents pianist David Montgomery in a program of Schumann, Liszt, and Chopin. The al bum begins with Montgomery opening the studio door, walking to the piano, seating himself at the occasionally squeaky piano stool, and announcing his first number. Clearly audible is the slightly squeaky shoe of his page-turner, who also sometimes gets caught up in the livelier passages and taps his foot in tempo.

The other binaural direct disc is a bit more spectacular, featuring seven jazz performers (though not all at once) in Woofers, Tweeters, & All That Jazz.

Pianist Art Lande is perhaps the best known of the jazzmen, and the arrangements of the four original tunes are by James B. Treulich. This session spread the instrumentalists around the studio, with a live "dummy" in the center wearing the Sennheiser condenser binaural mikes. During some pas sages, some of the instruments are wheeled around the studio while they are played, and to top it all off, sound effects of thunderstorms and rain are played through stereo speakers in the studio during one number. The latter which might have been passable in stereo loudspeaker listening-sounds canned and unnatural through head phones. Producer/engineer Leo de Gar Kulka comes up with a great description of binaural's effect in the liner notes, referring to its "sensuously expansive circular sensations." The al bums are Lab Series 5 and 7 respectively, and should still be available from Sonic Arts Corp., 665 Harrison St., San Francisco, Cal. 94107.

By the way, there are some Holophonic effects on two of Pink Floyd's albums, The Wall and The Final Cut, also available on CD. It appears these effects are limited to sound which was recorded Holophonically by Hugo Zuccarelli, but the entire albums may have been run through the Holophonics processor--it is not clear from the notes.

Headphones vs. Stereo

More people are enjoying their mu sic through headphones today than since the days of the crystal radio. And what a giant improvement has been made in stereo headphone quality in the last several years! Today the best ones--especially the electrostatic variety--rival and even surpass some of the most lavish loudspeaker systems as to frequency response and low distortion, and at a fraction of the cost.

The Walkman revolution has millions listening to their music wherever they are and no matter what they are doing. Yet all of these folks are hearing source material that was never de signed for headphone listening! The separation factor is the primary difference, though there are many others.

Everyone with stereo headphones is hearing grossly exaggerated separation that puts half of the orchestra at the left side of the head and the other half at the right side. They are also hearing greatly exaggerated dynamic levels designed for speaker listening rather than headphones. At very high listening levels, hearing damage could occur. Some headphone manufacturers have offered mixing boxes which can blend the two channels as de sired, but this does not make the result binaural, by any means.

This huge headphone audience is the perfect audience for binaural ready and waiting. A few prerecorded cassettes have been issued in "Mixed for Headphone Listening" versions, but this again is far from binaural since the music was not originally recorded binaurally.

In addition to increasing musical enjoyment and participation immensely, a pair of binaural mikes or a dummy head, together with either a portable recording cassette deck or a portable PCM-type unit and portable VCR, can be put to many nonmusical uses by the consumer. These can include taping business conferences and panel discussions. With binaural, every voice will be clearly heard-no one will sound "off-mike." And transcribing will be a breeze-just from the location of voices, there will be little doubt who is speaking. Stage plays and rehearsals can also benefit in a very practical way from binaural recording. Even if sever al people talk at once, each can be clearly singled out. (Edward Tatnall Canby has written at length in his Audio column about some of these binaural boons.) As for recording live musical events, it is simple if you wear the mikes yourself. It will successfully cap ture the event with a you-are-there quality almost wherever you sit; there is really no "wrong" mike location. (Be sure to get permission from the organizers of the concert, of course. And don't move your head.) Binaural is a thrilling experience for the first-time listener. If you haven't heard it yet, give it an ear-or rather, two ears. Let's get this show "phased in" soon!

References

1. Sunier, John, The Story of Stereo: 1881-, Gernsback Library, New York, 1960.

2. Kapeller, Ludwig, "Radio Stereo-phony," Radio News, October 1925, pg. 416.

3. Wood, Albert B., A Textbook of Sound, Macmillan Co., New York. 1930.

4. Martin, W. H. and Harvey Fletcher, High Quality Transmission and Reproduction of Speech and Music," Journal of the AIEE, March 1924.

5. Doolittle, F. M., "Binaural Broad casting," Electrical World, April 25, 1925, pg. 867.

6. Garner, Louis E., Jr., "Stereo Then and Now," Radio-Electronics, March 1959, pg. 53.

7. Fletcher, Harvey, "An Acoustic Illusion Telephonically Achieved," Bell Laboratories Record, June 1933, pg. 28 (reprinted in Audio, July 1957, pg. 22).

8. "The Reproduction of Orchestral Music in Auditory Perspective," Bell Laboratories Record, May 1933, pg. 259.

9. Wente, E. C. and A. L. Thures, "Auditory Perspective-Loudspeakers and Microphones," Electrical Engineering, January 1934, pg. 24.

10. "Binaural Recordings Add New Dimension to Recorded Music," Electrical Engineering, December 1952, pg. 1,156.

11. Steinberg, J. C. and W. B. Snow, "Auditory Perspective-Physical Factors," Electrical Engineering, January 1934, pg. 17.

12. Moura, Brian, "Q-Biphonic Sound," Evolution/4-Quad, January 1980.

13. Mori, Fujiki, Takahashi and Maruyama, "Precision Sound-Image-Localization Technique Utilizing Multitrack Tape Masters," Journal of the Audio Engineering Society, January/February 1979.

14. Zarin, Adrian, "Three-Dimensional Sound for Video," R-e/p, December 1984.

(Audio magazine, Mar. 1986)

Also see:

Audience Involvement Through Use of BINAURAL SOUND (Nov. 1972)

Binaural Overview: Ears Where the Mikes Are--part 1 (Nov. 1989)

Illusions for Stereo Headphones (Mar. 1987)

Headphones around the house (May 1974)

Headphones: History and Measurement (May 1978)

The Filter in out Ears (Sept. 1986)

Confessions of a Loudspeaker Salesman (Mar. 1986)

A Compact Introduction to the Compact Disc (Apr. 1986. CD)

= = = =