Dear Editor

Side Tuning Helps

Dear Sir: As Director of Engineering for a major radio outlet in this area and as a Consulting Engineer for a number of other stations both here and abroad, I am most aware of the quality (or lacking thereof) in the vast majority of radio receivers on the market today.

Many radio engineers are getting wise to this fact and are doing something about it by "pre-equalizing" their audio before it is fed into the stations transmitter.

The high-frequency response of many receivers (especially automobile and lower priced home units) can be improved somewhat merely by side tuning slightly. To do this, it is necessary to tune the receiver in the normal fashion and then slightly mis-tune it either towards the higher end of the band or towards the lower end of the band. Choose which ever sideband gives you the least distortion. This type of tuning takes advantage of the high frequency energy which is concentrated in the station's sidebands.

(Side tuning is most effective on receivers which lack selectivity.) Many receivers that incorporate ceramic filters or sharply tuned i.f. strips to increase the selectivity are subject to severe high-frequency distortion when tuned to the sidebands. This is due to the steep tuning slope of circuits within the receiver and obviously the only answer for these receivers is a reduction of the selectivity (or Q) of the i.f. and/or r.f. amplifiers within the set.

It is also interesting to note than many engineers feel that since receiver manufacturers have reduced their high frequency response to insignificant amounts, the broadcasting stations need not exceed these very poor specs. I feel that the practice of reducing the high-frequency energy within the broadcast station is extremely unwise because it deprives those few owners of truly find receiving equipment of the quality that they (the broadcasters) are required by law to uphold.

If you suspect that there is a problem with the frequency response of the station to which you listen, you might try side-tuning. This will allow you to hear the sidebands more easily and thereby determine if the response deviation is within the station or within your receiver.

I would life to hear more from other Broadcast Engineers regarding the practice of pre-equalizing the signal at the station and would be more than happy to be of help in solving audio problems either within the stations or with receiving systems in general.

Frank L. Berry, Frank Berry and Assoc. Highway 540 West Winter Haven, Fla. 33880

Construction Articles

Dear Sir:

I wish to commend and thank Audio for your publication of the article "Transient IM Distortion In Power Amplifiers" in February, 1975, and for your subsequent construction article "Build A Low TIM Amplifier" in your current (Feb., 1976) issue.

These articles appear to be a departure from the type of material Audio has published in recent years.

hope they signify a trend to return Audio to its previous status of a pioneering publication in its field, such as it was under C.G. McProud.

Jack L. Boyle, Phila., Pa.

Critic's Comparison

Dear Sir: It was an interesting move to contrast the differing viewpoints of critics Jon Tiven and Michael Tearson and their ideas concerning Joni Mitchell's The Hissing of Summer Lawns in your March, 1976 issue.

As a professional recordist and musician, having spent years in radio broadcasting, I feel that a major point was brought out very plainly and uniquely. Why is some music labeled "progressive" over and above other music? Why are some artists constantly turning out new and fresh ideas whereas others seem to release the same album time and again with modified lyrics and chord patterns? The answer lies in their approach to rock music; their overall concept of the ideas they're putting on their recordings. The answer also lies in the subjective response of the listener, or in this case, the critic.

Please look back into the March, 1976 issue and compare the two critiques. Note the major differences in the performance ratings: Tiven gave her a C; Tearson gave her an A+. Given the fact that the evaluation of a performance is a purely subjective phenomenon, this writer is drawn into the texts of the articles to discover the reasoning behind the discrepancy.

The Tiven review is written entirely from the viewpoint of "What should a woman sound like when singing 'pop/rock'?" He already knows what he wants to hear. This predisposition is understandable. Since the dawn of music prior to the rise of jazz, music has been evaluated from the standpoint of convention (with the exception of those innovators who, though breaking convention, were so strong they changed the direction of music, thereby allowing evolution). On the other hand, the Tearson review was written from what the critic heard, not what he expected to hear.

His performance rating reflected what Joni Mitchell did, not what she was expected to do. This, in my estimation, is not only more realistic, but it more closely parallels the ideals of "Progressive" music. The artists perform what they feel.

I have betrayed my own subjective position. I dearly love Joni Mitchell's music. But I certainly do not condemn a man who doesn't appreciate her style; that is for him to decide. But I greatly resent the insinuation that music must follow pre-established developmental guidelines. It is this approach that precludes many people's enjoyment of music like that of Bob Dylan: he doesn't seem to sound like other artists.

Thank you. Your magazine is excellent.

John P. Fiksdal, Media One, Inc.

Sioux Falls, S.D.

================

Behind The Scenes

by Bert Whyte

ONE OF THE more interesting and provocative papers given at the 52nd convention of the Audio Engineering Society in New York was entitled, "Towards a More Natural Sound System," by Leslie Hay of Westinghouse Airbrake Co. and Dr. John V. Hanson, Electrical Engineering Dept., University of Waterloo, Ontario, Canada.

In essence, what the authors proposed was a new configuration of quadraphonic sound, in which three channels would be used for the front "sound stage"-a left, center, and right loudspeaker-and the fourth channel would be in the rear, rather than the left and right front, and left and right rear channels as in the conventional quadraphonic layout.

In the introduction, the authors presented some well-documented facts pertaining to the perception of direct and reflected sound in the concert hall environment. In the listening room, under normal stereo playback conditions, the accurate spatial location of sound sources is possible only if the auditor is on a line equidistant from both loudspeakers, and subtends an angle to the loudspeakers of approximately 60 degrees. At angles greater than 60 degrees, they contend that a hole in the middle effect occurs, and sound sources tend to be localized at the loudspeakers. While this is basically true, the condition has been somewhat alleviated for some years now by the practice of mixing the output of a center stage microphone into the left and right channels, which on playback provides us with the so-called phantom center channel.

Getting back to concert hall listening, the authors note that "reflected sound is delayed with respect to direct sound, is of lower intensity, and impinges from all directions. It contains ambience or depth information relation to the acoustics of the concert hall, but no directional information. Also, the perception of distance to the sound source is a function of the ratio of intensity of reverberant sound to the direct sound. This ratio may be defined as the sound quality depth. In normal stereo reproduction, the ambient sounds that contribute to depth are perceived to come from in front of the listener, whereas in the live situation, ambient sounds impinge from all directions." The authors state that standard stereo reproduction thus suffers from three major shortcomings when compared to natural concert hall sound-poor source location stability and accuracy, limited listening area, and incorrect ambience.

Mr. Hay and Dr. Hanson go on to comment that although present quadraphonic recording techniques reproduce direct stage sounds from two front loudspeakers (not entirely true, because there is some ambient or reflected energy in the front channel signals) and the two rear channels provide two ambience signals for subsequent improvement of depth perception, the other two reproduced stereo faults of poor source location stability and limited listening area remain.

The authors also argue the point that having two discrete rear signals permits the total surround sound type of quadraphonic reproduction, but this is not a natural sound environment. This is, of course, a controversial matter. As has been stated many times before, there are a few, very few, pieces of music scored for "rear of hall" sounds, e.g. the brass bands in the Berlioz Requiem, the children's chorus in the Mahler 3rd Symphony, and the antiphonal music of Gabrielli and Monteverdi. To this we must add any modern works in which the composer is aware of surround sound quadraphony and deliberately scores his work to take advantage of the medium. There are also those works, such as Carmina Burana, which lend themselves to the surround sound quadraphonic treatment. Nonetheless, this music and any other standard work which has been recorded in surround quadraphony must be considered a contrived product. Multi-track surround sound pop music is, of course, a totally contrived product of the studio, with no counterpart in real time.

The authors state that in the quadraphonic listening tests they conducted, listeners found it difficult not to turn around to face a sound perceived to come from behind them, and they complained of unnaturalness when this occurred. I think what they meant here was that even when the rear channels are just used for ambience, if the amplitude of the rear signals is too high, discrete instruments are perceived, and this is unnatural.

This is a situation which has occurred all too frequently in dealer listening room demonstrations of quadraphonic sound and is partially the result of high noise levels in the demo room, with the salesman turning up the rear channels to override the noise, along with desire to show that he really is playing four-channel material.

New Quadraphonic Configuration The authors, however, agree that the rear channels should be used only for the reproduction of hall ambience, but that in consideration of the non-coherent, non-directional nature of the ambient sound, that a single ambient signal delivered to two (or more) rear loudspeakers would suffice. With only a single rear signal, the remaining three channels can be used to form the optimum stage sound, including a discrete center channel, thus the three-plus-one system. Their contention is that this configuration of the four available channels should provide a better approximation of the concert hall acoustic environment than the standard quadraphonic system. The authors describe interesting experimental data to support their three-plus-one system.

Quoting from their paper, "Professional quality live recordings were made of the Kitchener-Waterloo Symphony Orchestra, using both standard quadraphonic and 'three plus-one' arrangements. Five microphones were used ... three directional microphones in front of the orchestra for left-front, center-front, and right-front signals, and two omnidirectional microphones near the rear of the hall for left-rear and right-rear signals. For the quadraphonic recording, the center-front microphone was not used, and for the three-plus-one recording, the two rear microphones were mixed to provide one rear channel signal.

"Listening tests were performed in a carpeted living room 22 feet wide by 20 feet deep, with reasonably well damped acoustics. Five loudspeakers were used to match the microphone placement. These were all wide-range direct radiators, the center-front unit having a wide dispersion angle.

(Nothing is said about the dispersion characteristics of the other loudspeakers, but one presumes they are not dissimilar from the center front speaker.) A switching arrangement coupled to colored lamp indicators controlled the loudspeaker energization ... quadraphonic using the four corner speakers and the three plus-one system using the three front speakers plus the rear speakers driven in parallel. The switch enabled listeners to compare the white and yellow quadraphonic or three-plus-one systems. Seating for 18 listeners facing front was provided. Four groups participated in the tests, a total of 71 persons. The participants were largely from the university community, students, staff, and faculty. Thirty-three of these people claimed to be high-fidelity enthusiasts, however, no discernible difference was found between the response of the audio enthusiasts and others. Each listener was given a data book in which he recorded his seating position, answered some questions concerning his musical experience, and recorded his responses to other tests.

"The first part consisted of image location tests, for example, central image location, LF, RF channels only; test tone location, solo instrument location, and instrument location using quadraphonic and the three-plus-one recordings. The listener was asked to mark the apparent source locations on appropriate diagrams in his data booklet. These were checked later against the known locations and results tabulated. The second part of the test consisted of A/B comparison listening, and the participant was asked to answer the following questions:

"1. Which system most clearly defines the positions of the instruments?

"2. Is there any noticeable change in the front sound between the two systems?

"3. Is there any noticeable change in the rear sound between the two systems?

"4. Is there any noticeable change in depth (ambience) between the two systems?

Image Localization

"Among the results of the tests are that center-stage sources are accurately located at any listening position when three front channels are in use, whether these sources are solo or in combination with the orchestra." Stereo location in the rear is 'focused,' resulting in a narrowing of the perceived rear sound stage. Most listeners were position conscious and preferred the ease of source location in the three-plus-one system, and many equated this with an increase in naturalness over quadraphonic sound.

Depth here is equated to ambience and is the ratio of rear (ambient) to front (direct) sound. Some preferred the quadraphonic system for this reason, although this characteristic is sensitive to listener front/back position in both systems. The listener near the back hears a stronger ambient signal than one near the front, in the concert hall there is no such gradient." The authors conclude that a significant improvement in naturalness of sound in a living room can be obtained by the redistribution of the four channels available in quadraphonic systems to form the three-plus-one system. They suggest that the ambient sound level gradient can be significantly reduced by employing a line of loudspeakers (possibly planar foam strip speakers) around the sides and rear of the listening room, driven by the single ambient signal.

The foregoing has outlined the experiments of Mr. Hay and Dr. Hanson.

For the record, I agree absolutely with the findings and conclusions in this study. I have been an advocate of three-channel sound, in the sense of a left-front, center, and right-front loudspeaker set-up fed by three discrete signals, for many years and have made many recordings in this format.

Older readers may recall that I almost got three-channel tapes on the market from Mercury in 1955 and Everest in 1960. Classical in Three-Plus-One Like many other good things, the chances of the three-plus-one system being adopted by the recording companies is remote. Perhaps some venturesome small company might take a crack at it as an audiophile product.

After all, it really is a very simple thing to do! However-try this one for size-there are thousands of fine three-channel recordings on half inch tape in the record company vaults. For many years literally all classical recordings were made in this format. Now, take an outfit like the Barclay/Crocker Co. that I wrote about last month. They are going to issue their own prerecorded tapes. If they would lease some selected three channel masters, get rid of 8-10 dB of noise by running them through a professional model of the Phase Linear autocorrelator (said to be forthcoming), then duplicating them with Dolby B, just as straight three-channel productions they would be sensational. Now, with the remaining channel on the four-channel tape head, by use of one of several devices for adding delay and reverberation (as outlined in my column some months ago), these tapes could be issued in what would essentially be the three-plus one system. Alternatively, the audiophile could take the three-channel prerecorded tape, and utilizing some of the newer, less expensive delay and reverb equipment coming onto the market-and about which we will soon be reporting-create his own rear ambience channel. I have the tapes and the needed equipment, and I will let you know the outcome of my experiments very soon. In the meanwhile, are you listening Barclay/Crocker?

==================

Tape Guide

by Herman Burstein

How Often To Clean Heads

Q. I have an Advent cassette recorder and am wondering and concerned about head wear. Advent's instruction manual tells you to clean the heads every 10 to 15 hours, whereas most tape recorders suggest every 50 hours.

-C. L. Moody, Virgina Beach, Va.

A. Usually the manufacturer knows his own machine best, and it is wise to follow his advice about cleaning and other maintenance procedures for his product. From what I have seen, most tape recorder manufacturers recommend cleaning and demagnetizing the heads after about every 8 hours of use, i.e. after the equivalent of a normal working day.

Tape "Dust Bug"

Q. I am quite happy with my tape machine except for one problem which I find frustrating: drop-outs. I believe there is nothing wrong with the machine, and since I only notice the drop-outs because of a combination of factors, this makes the fault more obvious. Maybe I am just very fussy! I record mostly steady, pure tones (solo flute) on which any defect is bound to be more noticeable. I use earphones, so that room reverb does not mask the drop out.

My machine is quarter-track and uses no pressure pads. I am young and my hearing extends beyond 17 kHz; the problem is most obvious at higher frequencies.

Head cleaning was not enough, so I tried putting a piece of cloth in the tape path to wipe the surface of the tape, attaching it to the tape tension arm. This has essentially licked the problem. However, can this "dust bug" damage the tape?

-Pierre Lewis, Edmonton, Alberta.

A. Tape imperfections--in the tape or on it in the form of dust, dirt, etc.--cause drop-outs. The wider the track, the more chance these imperfections have to average out; that is, drop-outs are less likely to be noticeable. Some tapes are better than others with respect to this problem; they have fewer irregularities in the oxide. Your solution, provided it does not noticeably increase wow and flutter, sounds like a suitable one. It doesn't seem that your "dust bug" would have any more effect on tape wear than does a tape head and perhaps less. It also may be that tape tension has increased as the result of your attaching a cloth to the tension arm, and this may be helping to reduce drop out.

S/N vs. Response

Q. I have a TEAC tape deck and am interested in having it re-biased for low-noise tape. I recently had it tested at a local place, but they said frequency response would probably suffer although S/N would improve. Another dealer said this is untrue. I am interested in improving the S/N ratio, but not at the cost of reduced frequency response. Can you give me an objective opinion?

-Shelby Remington, New Haven, Conn.

A. Without going into the matter of who said what, and how correctly, it should be possible, through an appropriate increase in bias, to adjust your tape deck so that when using low noise tape you will get an improvement in S/N along with treble response at least as good as and perhaps better than before. When having your machine re-biased by a competent technician, bring along a reel of the tape you plan to use. If the technician is conscientious as well as competent, the results should be satisfactory.

=============

Audioclinic

by Joseph Giovanelli

Right Channel Lacks Bass Q. The right channel of my receiver does not have enough bass. On any material, the right channel will reproduce any low bass note correctly but it just does not give the proper sound of, say, a bass drum punch. Adjusting the balance does not help. The bass will be centered, but the "kick" will still be in the left side only. Repairmen state that there is nothing that they can do because the right side reproduces any bass note correctly. Please advise.

-Bob Powers, Brecksville, Ohio

A. It is not unusual to find an apparent lack of bass in one channel of a music system. Yet, that channel will measure just as well as the good channel. This apparent lack of bass is usually the result of nothing more than a room acoustics problem.

To determine whether this is the situation, interchange the speaker leads, that is to say, the lead connected to the left speaker should be reconnected to the right channel of the amplifier and vice versa. Use a monophonic program source and listen to the sound quality. If the deficiency of bass now occurs in the left channel, then you will know for sure that something is wrong with the amplifier. If, on the other hand, the bass is still deficient on the right channel, then the problem will be that of room acoustics. I doubt that loudspeakers will be the source of the problem, unless the speakers are not a matched pair.

In the event the amplifier is found to be lacking in bass on the right channel, despite the information supplied you by repairmen, obtain a service manual from the manufacturer of the receiver and make step by step checks, using the information supplied in that manual. Compare frequency response stage by stage between the left (good) channel and the right (bad) channel. You will reach a stage which shows a lack of bass, and, of course, it is this stage which must be checked into further to disclose the exact cause of the low-frequency loss.

Disc Rumble

Q. I have a problem with intrusive rumble when I play stereo discs. This happens during quiet passages when I listen to stereo. When I switch to mono, the rumble often goes away. I have thought the turntable is not at fault. Can it be a defective cartridge? Maybe it's my records?

-Eugene E. Kucza, Westchester, Ill.

A. A turntable can produce rumble such that, when the system is switched to mono, it is somewhat lower. This is because the rumble component in the machine may be mostly vertical, and the response of the mono-connected pickup is purely lateral. Therefore, we cannot immediately rule out the turntable. However, if it happens only with certain discs, or to a markedly-differing degree with various records, we know that the discs are at fault, not the turntable. There is nothing you can do about faulty discs.

Some rumble can be introduced during the cutting process. Pressing problems having to do with the flatness of the bed holding the stampers in the press can also cause noise. Usually this sound is "roaring" rather than that of a low-pitched "rumble" though.

==================

ADs:

STANTON Magnetics

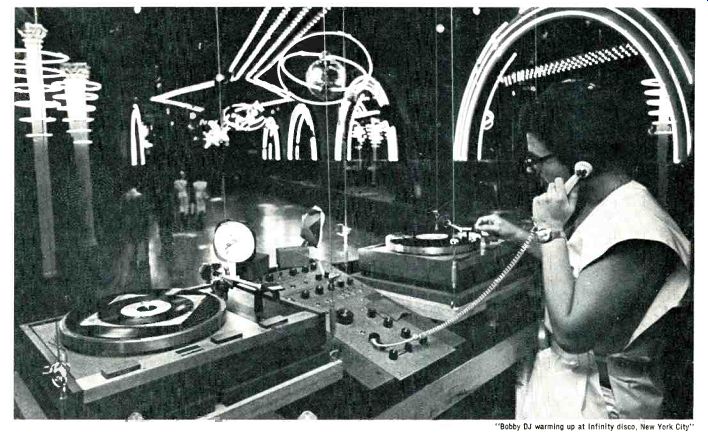

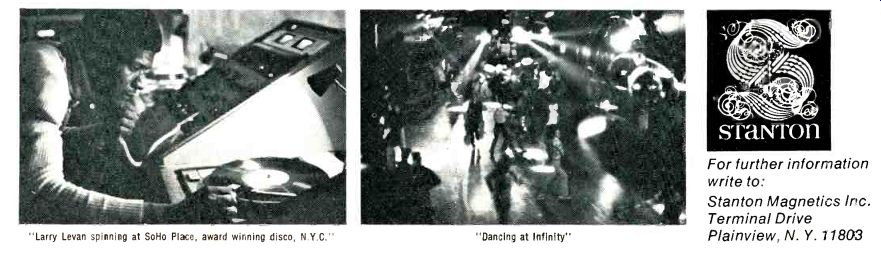

Disco use challenges a cartridge ... that's why Stanton is the first choice of disco pros, as it is of broadcast pros Discotheques represent one of the most grueling professional situations for a pickup that can be imagined. Not only must the cartridge achieve a particular high level of sound excellence, it must do so in the "live environment of back cueing, slip cueing, heavy tracking forces, vibration and potential mishandling ... where a damaged stylus means much more than lost music; it means lost business.

For such situations Stanton designed and engineered a new cartridge...the 680EL. Its optimum balance of vertical stylus force, compliance and stylus shank strength makes it a star performer for "Larry Levan spinning at SoHo Place, award winning disco, N.Y.C."

"'Bobby DJ warming up at Infinity disco, New York City" any physically demanding situation, whether it be disco or radio broadcast. However, if modesty of investment is critical, then choose the 500AL, a beautiful but tough performer that has become deservedly known as the "workhorse" of the broadcast industry.

If your need is for disc-to-tape transfer where the absolute in sound excellence must be achieved, the Stanton 681 Triple-E has to be the only choice. In fact, whatever the need ... recording, broadcast, disco, or home entertainment ...your choice should be the choice of the Professionals ... STANTON. "Dancing at Infinity" For further information write to: Stanton Magnetics Inc. Terminal Drive Plainview, N. Y. 71803

=============

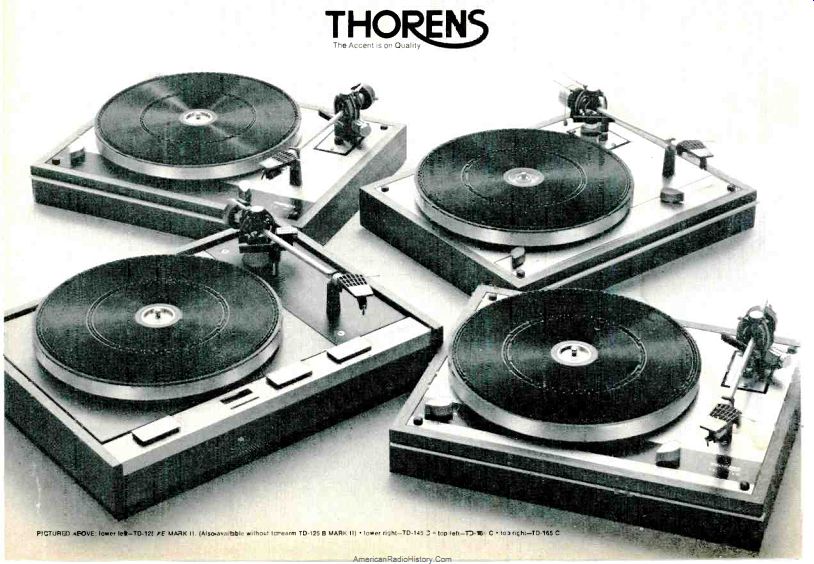

Thorens

It all started in 1883 in St. Croix, Switzerland where Herman Thorens began production of what was to become the world's renowned Thorens Music Boxes.

For almost a century Thorens has pioneered in many phases of sound reproduction. Thorens introduced a number of industry firsts, a direct drive turntable in 1929, and turntable standards, such as the famed Thorens TD-124.

Over its long history Thorens has learned that an exceptional turntable requires a blend of precision, relined strength, and sensitivity Such qualities are abundantly present in al' five Thorens Transcription Turntables. Speaking of quality, with Thorens it's the last thing you have to think about. At Thorens it's always been their first consideration. So if owning the ultimate in a manual turntable is important to you, then owning a Thorens, is inevitable.

ELPA MARKETING , INC. EAST: New Hyde Park, N.Y. 11040 WEST: 7301 E Evans Pd., Scottsdale, Arizona 05260

===============

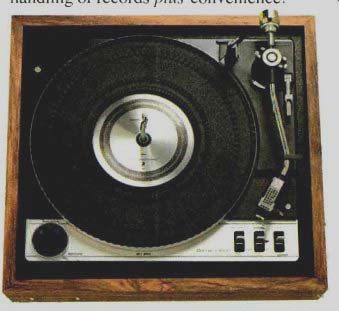

The Garrard 990B. And the argument ends.

There are almost no limits to what you can spend for a turntable. Nor to the refinements that can be built in.

The argument has been whether you can find a turntable at a sensible price, that really performs-giving away nothing important. Now with the belt-driven 990B, the argument is over. The 990B gives nothing away in any vital area, yet is priced to make it eminently accessible.

We believe the 990B is the best value Garrard has ever offered in its quarter century of designing and manufacturing high fidelity turntables.

The 990B is a single-play/multiple-play turntable and is fully automatic in both modes. That is, its arm indexes, returns to its rest and shuts off automatically.

All of which is more dependable than a hand ... that can be shaky or careless. And the mechanism that does all of this is disengaged during play. You get the gentlest handling of records plus convenience.

But more. In the multiple-play mode, your records rest on a two point support.

You don't have to balance them on a single center support. And pray.

And still more. A precision anti skating device eliminates distortion and record wear caused when the stylus is forced against the inner wall of the groove by rotation of a record. Even cueing is viscous damped in both directions.

All well and good. But what about performance? A glimpse at some specifications tells the story. Rumble: -64dB. Wow: 0.06%. Flutter: 0.04%. These are possible because your records are cushioned on a full size, 5 lb., die-cast, dynamically balanced platter-belt driven by a motor that combines an induction rotor for starting power and a synchronous section for constant speed.

You can even solve the problem of off pitch recordings with the variable speed control monitored by a strobe disc.

One final word. The S-shaped, lightweight, aluminum tonearm boasts low mass and low friction. But here's the thing. The 990B's tonearm can track as lightly as i gram. Protection and performance indeed.

There are other turntables in the price range of the 990B that offer some of these features and specifications. The 990B has them all and at a price that's sensible--under $170! Which clinches the argument.

For a copy of the Garrard Guide, write: Garrard, Div. of Plessey Consumer Products, Dept. C, 100 Commercial St., Plainview, New York 11803.

Garrard--The Automatic Choice.

------------

++++++++++

--------------

(Audio magazine, 1976)

Also see:

Record Cleaners Revisited/B.V. Pisha

Audio's Crescendo Test/Richard C. Heyser

= = = =