Making Records

by Ralph Cushino [ Ralph Cushino is Director of Engineering, Capitol Records, Inc., Hollywood, Calif. 90028. ]

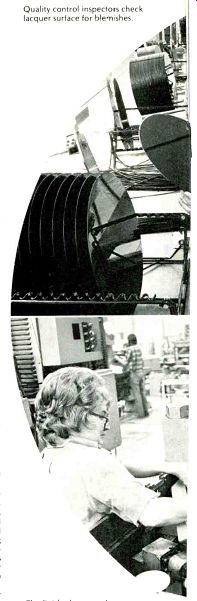

-------Quality control inspectors check lacquer surface for blemishes.

-------The finished stamper is put into the record pressing machine.

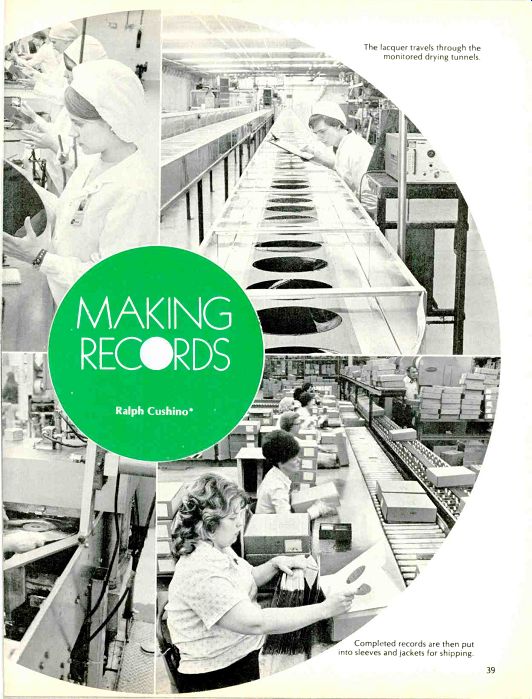

------------ The lacquer travels through the monitored drying tunnels.

----------- Completed records are then put into sleeves and jackets for shipping.

A RECORD. A simple piece of plastic molded with grooves? Not quite. The vinyl disc you purchase in your local record or hi-fi shop is the end product of a highly critical, multi-step process of precisely controlled timing, temperatures, and chemistry-steps that make a big difference in the sound you hear when you place that innocent black platter on your hi-fi turntable.

In fact, the record's journey through lacquer manufacturing plant, recording studio, and record-pressing plant to the sales bin probably took six months or more. And throughout the process, each record has been tested and rechecked at least a dozen times so that you may enjoy sounds as close as possible to those that were recorded by the musicians themselves.

While the songwriter is still composing the music, lacquer-coated mastering discs are being manufactured at one of two plants in the United States. These extremely critical discs will bear the impressions made by electronic impulses that ultimately will be transferred through several metal platings to the final mold used n mass production of records.

Making A "Lacquer"

The base of mastering disc, commonly called a "lacquer," is a smooth, circular aluminum blank, slightly larger in diameter than a finished record and approximately 0.050-in. thick. It has a shiny, highly polished surface because it has been calendered by the aluminum manufacturer to a surface smoothness of 2 micro inches (500 angstroms). At Capitol Magnetics Products' plant in Winchester, Va.-where the accompanying photographs were taken-a unique step is then taken, lapping which consists of grinding away the disc's surface and then re-polishing it one additional time. This insures that no surface imperfections have been ground into the disc's surface in the calendaring. These imperfections, evident in this stage as tiny lines, rolling marks or pits, would show up later in the finished lacquer. Capitol has also found that a lapped surface results in better adhesion between aluminum and lacquer and is the best method for obtaining disc flatness. If the disc is not absolutely flat, it may not cut well and the sound of the final record will reflect the uneven surface.

Once the disc has been polished down to acceptable surface specifications, it is nearly ready to receive a coating of lacquer. However, before coating, this smooth disc will have to pass through five chemical baths, a water wash, a drying process, and be checked once again before it is ready to be sent to the coating room.

As the aluminum blanks are being lapped, etched, and dried, a special nitro-cellulose lacquer formulation is being blended, filtered, re-filtered and then de-aerated in a series of large tanks in another part of the plant.

Samples are tested regularly to determine the lacquer's chemical purity, composition, viscosity, and dispersion and to check for air. Any lumps or bubbles in this complex mixture must be removed before coating or they may later rise to the surface of the coated disc and cause noise clicks, pops or other audible imperfections when the disc is cut.

An exact balance of ingredients is also required so that the product will perform reliably through all the various electrical and chemical processes that will be performed on it during the manufacture of a record. For instance, a lacquer must not only cut well in the recording studio, but also process well once it has been cut and then sent to a manufacturing plant for plating and creation of the molds from which multiple copies of the record will be made.

The lapped, cleaned, and dried discs come together with the lacquer in the coating room, an environment controlled "white room"' filtered for Class-100 Air-the same standard of air cleanliness necessary for space components and surgical drugs. Air in this room must have less than 100 particles of dust, all less than 0.3 micron in size, per cubic foot of air. People working near the coating machine wear dust free lab coats and caps and at no time touch the disc's surface.

They also do not allow two discs to touch; if one disc even leans against another, the surface will be ruined.

The disc is coated on one side at a time and then carried by conveyor belt through several hundred feet of drying tunnels. Long, slow drying at correct temperature is necessary for even evaporation of gases and solvents used in blending materials which make up the lacquer. Rushed drying at high temperatures would boil off solvents too quickly, creating pin holes and blemishes on the surface. A quality finished lacquer has the smoothness of ground optics or 100 angstroms (0.4 millionth of an inch) in order to provide optimum low-noise properties.

After drying, the lacquer disc is [...]

[...] room specially designed for the proper acoustics, where engineers record the musicians, producing a master

[...] Once the reference lacquer is finished, it is sent back to the recording studio where the artists, producers, anrd cnunrf PneinPers listen to it. If [...]

-------- The silver mother is carefully stripped from the master lacquer.

... final plate from which the records will be made. Since the final mold must be a negative impression (the lacquer master was a positive impression, the silver a negative, and the nickel mother was positive), the nickel mother is sent back to electroplating for a final nickel mold called a "stamper." Later this stamper will be inserted in a pressing machine and used to stamp out records.

Several stampers are usually made from each mother since stampers wear down during the manufacture of records. For extremely long runs, such as for a record made by one of the Beatles, as many as 1000 or more stampers may be used.

As each of the three molds (silver, nickel, and stamper) is made, a specialist carefully peels the new material from its mold and checks to see that the new mold is flawless. The worker then places the material in a metal trimmer to cut away any excess material. In the next step, the mold is placed on a revolving turntable and carefully cleaned to remove any stray particles which might have lodged on the surface or in the mold's grooves.

Alcohol is used to clean silver masters; jewelers rouge is used for nickel molds.

Testing of the "Mother" Because the mother is so critical, this mold is sent to the testing area when finished to be critically checked for sound quality. This is the first time it can be played! Using specially designed electronic playback equipment, the quality control inspector listens to the audio signal. If any pops or groove damage are evident, the inspector either rejects the mother outright or, if the problem is minor, inspects the mother under a special mi croscope and then carefully makes the repair with a small needle-like instrument.

Correct testing of the mother is absolutely critical to getting quality finished records. Clicks and pops must be picked up here or they will be transmitted through the remaining molds into the pressing process.

After the final production mold, a stamper, is trimmed and cleaned, it is taken to the centering machine where a worker determines the exact center of the mold using a microscope with a graduated screen. A hole is then punched out which assures accurate location of the final spindle hole. At this point in manufacture, the stamper is also back sanded, die punched and formed to fit the mold configuration.

Great care is taken that nothing happens to the stamper during all these processes. If the stamper is rubbed up against metal, for instance, it might get a tiny surface scratch, which would result in a clicking sound in the final record.

Each record has two stampers, one for each side. These final molds are placed in the pressing machine, permitting stamping of the final product on both sides at once.

Pressing The record you buy in a music store is made of a vinyl compound which is mixed and pumped to the pressing machine area. Here it is released down through overhead pipes into the pressing machine where it is converted into small lumps known as "biscuits." Labels are attached, and the two stampers clamp together to press out a completed record.

Like all the other phases of record manufacture, this process must be carefully monitored. Vinyl must completely fill the stamper's grooves, for instance, or sound quality will be affected. Also, stampers must be regularly inspected for wear, since a stamper that is used too long will produce records with noise.

Once records are pressed, they must be uniformly cooled. If cooling is not done properly, warping can result. Usually, completed records are placed on a spindle under weight.

Each fully automatic pressing machine at Capitol Records is able to produce about 1,800 12-in. records per day. A large pressing facility may have as many as 50 machines permitting production of up to 90,000 albums in a single day. Thus, record manufacturers can keep up with the consumer demand, which, last year, amounted to 276 million albums and 204 million singles.

The completed records now have only a few steps of their journey left.

Once again, they are visually checked and inspectors listen to samples from each run. Any discs with chemical stain, scratches, dents or damaged grooves are discarded. Plant workers then carefully place all records passing final inspection into protective sleeves, and, in the collating area, insert them into album jackets along with other materials such as librettos and photos of the recording star. The albums are then packaged and prepared for shipment to record stores all over the world where you may buy the record and enjoy the sounds recorded in that studio many months ago.. From recording microphone to a grooved vinyl disc, making a record is a complex and exacting process, but it is one that lets you enjoy your favorite sounds over and over again in your own home.

(Audio magazine, 1976)

Also see:

Build A Boost--Rumble Filter/Dick Crawford (June 1976)

Equipment Profiles: E88 "Eclipse" Model 2240 Electronic Crossover/Leonard Feldman; Garrard Model 86SB Turntable/George W. Tillett (July 1976)

Audio in General (Departments): Audioclinic/Joseph Giovanelli; Tape Guide/Herman Burstein; What's New In Audio ; Audio ETC/Edward Tatnall Canby ; Behind The Scenes/Bert Whyte (July 1976)

= = = =