by H.W. Hellyer

BRAKES ARE MEANT to stop things. Although their malfunction is obvious when-in a tape recorder-they do not, more often the troubles caused by erratic brakes are those of binding, retardation, or incorrect timing. Diagnosis depends very much on a knowledge of the type of braking mechanism that is employed, how it should work, when it should work, and with what force. There are many different methods.

Basically, we are concerned with two different processes. First, and most obvious, we have to stop the spools in the shortest possible time without spillage. Secondly, and not so obvious, the correct tape tension must be supplied during playing, so that the tape enters the head channel without slap or flutter and leaves it without snatch. This operational braking is quite often the most difficult function to achieve.

The simplest type of brake is the peripheral pad-usually made of felt--which is spring-loaded to engage with the edge of the spool carrier. Levers hold it off during RECORD, PLAY, Or FAST WIND. But the simplicity can be deceptive. When the STOP key is operated, the timing of the brake action is important and quite elementary braking systems can still have offset levers or brackets which enable the feed-side brakes to engage fractionally before those retarding the take-up spool. During servicing, care must be taken to preserve these small differences in brake application. Quite often they will depend on the bending of a bracket, or the setting of a screw.

Testing such simple brake systems consists of an operational run, with sudden 'stop' action applied during any function. It is a common mistake to set brakes for 'normal' braking, ignoring the crash-stop conditions from fast wind in either direction, and with full or empty spools, to which the machine may be subjected as soon as it has left your hands.

Such simple systems, too, may depend for their effective friction on the condition of a felt pact. Constant use, variations of heat and cold, perhaps the throw-off from capstan or idler bearing of minute particles of lubricant, will all cause a skin of 'brake spoil'. The effect is insidious: the brake engages quite firmly and appears correct when inspected with the mechanism at a standstill. But at the important moment when the brake begins to apply friction, the tendency of the spools to skid can cause either spillage of tape or excessive retardation-drag-with the resultant stretch of tape and the danger of breakage.

Peripheral brakes should first be checked for soft felt pads, clean cork or composition pads or shoes, and free rubbers. The last remark may cause some puzzlement: free rubbers? But the type of brake that is a small rubber wheel mounted on a spring arm which is disengaged to contact the edge of the spool carrier or brake drum when `Stop' is selected is similar in principle to, though rather different in operation from the ordinary pad brake. The rubber wheel engages the running surface, turns briefly, then, as the spring pressure tightens, locks and grips. Usual trouble with this type of brake is binding of the wheel on its own spindle or bearing, with a consequent fierce application that is originally ineffective then too hard. The outcome is usually stretched or broken tape.

The cure, of course, is cleaning of the wheel mounting, easing of the spindle bracket, where this is pivoted, checking of the spring, cleaning and softening of the rubber (a bit of extra softening can help here-the wheel drives nothing) and resetting of the stops to ensure engagement at the right time.

Similar remarks apply to the simple pad brakes. Above all--keep 'em clean. Grit, dirt, oil, rubber parings, and other foreign matter spell death to brake pads, just as they do with your auto.

Where there may be some doubt about brake application, always err slightly toward the feed spool. During Play, this should come on slightly in advance, to keep the tape in correct tension through the head channel. Too much in advance, of course, means a retarded tape. The usual fault is the opposite, and a tell-tale spillage loop before the tape enters the first guide. No adjustment rule can be given, mechanisms differ in detail so much. Too often, the mechanic is left to decide for himself how much he shall bend, twist or screw the vital parts.

Servo-brake mechanisms require more than a simple 'off-on' adjustment. They work by applying a pressure to the braked drum which varies as the torque: the faster the drum is initially turning, the less the braking effect. A curve drawn to illustrate braking effect will show a pronounced difference in slope as the contact angle is increased, giving greater 'wrap.' The effect of greater wrap is not a 'tighter' brake but one that gives its retarding effect with a more rapidly increasing application.

The design problem is not one of working out the braking force, but of calculating the variation in that force between a full and empty spool rotating in one or the other direction. The servo brake tends to wedge itself on in the winding direction, i.e. the supply direction, and the contact angle, in the case of a band, or the wedge angle, in the case of a pad, has to be determined with some care. The outward force can be set, and the inward force calculated for differing loading conditions, and by reference to tables of coefficients of friction the angles can be worked out.

But like all carefully calculated plans of mice and men, external influences will make them go agley. The external influence in the case of tape recorders is inevitably dust, dirt, excessive heat, and a great growth of unwanted friction.

At first, the variation from 'as new' conditions is not noticed. By the time alarm bells ring in the mind, and the slowing spools are not as regular as they used to be, it is often too late. The cure may be to change the brake bands, reset the brakes ( relaxed springs can by now have made this necessary), or change the pads, which may be of cork, felt or some rubberized composition, but should never be replaced by something different.

Shoe brakes of different sorts are used in servo mechanisms and also in straight brakes. Often, the shoe will be shaped to give the needed servo action, and care must be taken to get the shape right when replacement becomes necessary.

Wear is the big enemy, always accelerated by dust, dirt, and heat. Polished brake bands, pads, and linings are frequent causes of spillage, brake snatch, or uneven application. It often takes longer to clean such surfaces than to replace the material. As the designer has such a ticklish job in working out what materials to use, do him the honor of using the same substance he has chosen, and not a bit of the lining from your old hunting cap. Cork is a common material, with felt running it a close second. Rubber is employed at times, usually when metal rims are to be retarded, and plastic or fabric bands, some of them made from specially treated and tensilized materials, form the basis of simple servo brakes.

In the domestic machine, application is generally direct-though there are notable exceptions that use solenoid operated brakes. But professional machines have larger spools, and are more often required to change direction, stop and start, or retard their motion from any functional operation. Auxiliary braking systems are thus employed. Stop braking takes two phases: the first is a rapid delay action, retarding the fast-moving spool, changing to a more gentle brake application as the spool decelerates. Relays with delayed-action circuits, and forms of braking magnets are often used. Quick acting brakes which bring the spools immediately to a halt if the tape breaks, or after it runs through, are also part of the studio machine's make-up. Many of these special brakes are now being incorporated in so-called `domestic' machines.

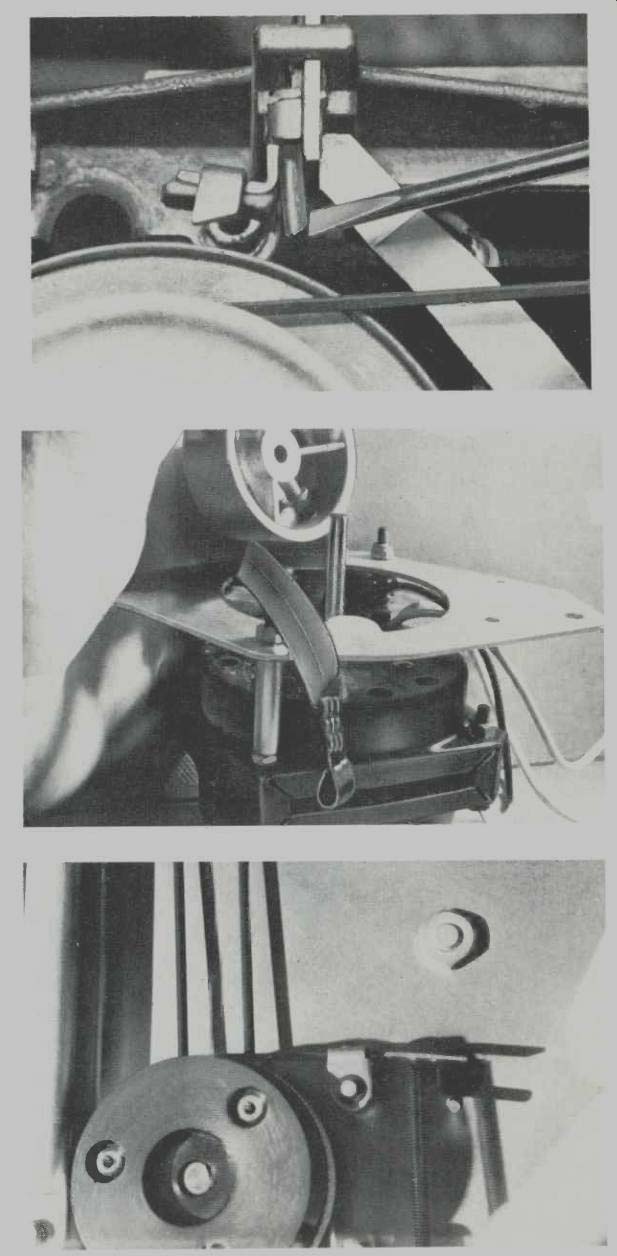

Fig. 1--Differential brake action provided by flexible tongue. Fig.

2--Simple

type of servo brake using fabric band, sometimes treated with graphite. Fig.

3--The servo brake on the Revox G 36 is a steel band and the drum is rubber

lined.

One of the special devices is the servo control brake. This is a form of electronic control which depends either on the rate of revolutions of the machinery compared with a standard-frequency reference source, or on a compared recorded track referred to the motor speed. Early forms were transistorized developments of the simple regulator--and not always as effective in practice as their designers may have wished. It seems likely that forms of servo speed control linked with servo assisted braking will become more common, and a section of this series of articles will be devoted to the subject when space is available.

In general, maintenance of braking systems is a matter for common-sense and knowledgeable inspection. Most frequent problem is wear and tear, broken cork or composition pads, polished linings, loose linkages, and bent brackets. It should never be forgotten that mechanical sys-. tems are interdependent. Brakes depend on clutches and drive systems: the one will show evidence of defects if the other is malfunctioning. An example is the rewind action which spills tape when stopped with a nearly full re-spooled tape. Premature braking may be suspected, but the trouble could be a combination of weak clutch action and `lazy' brakes.

Watch out for the 'double-action' brake, where the two brake brackets are linked by a common rod or lever, the frictional moment being provided by the direction of spool rotation. Some peculiar effects can be obtained by wrongly adjusting the linkages, and tests should always be made with full and empty spools, both sides, before assuring oneself all is well.

Watch out also for the compensated operational brake, where the angle of the tape over a rider pin is used to give the wedge of a brake a slight pressure against a supply spool carrier. The idea is to provide constant tape tension independent of the amount of tape on the spool. Like all good ideas, it is fine when it works, the very devil to adjust when it does not. Usual adjustment is at the pivot point, and should be made for maximum action with a near-empty spool.

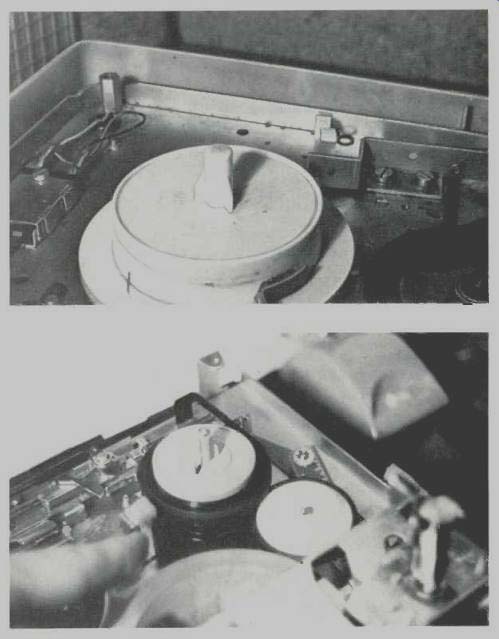

Fig. 4--(Top) Edge-contact brake as used by cheaper recorders. Fig.

5--Auxiliary

brake used by Sony at the take-up spool for the adjustment of tensioning.

(adapted from Audio magazine, Oct. 1970)

Also see:

Tape Transport Maintenance PART 7: Cassette Mechanisms (Jan. 1971)

Tape Transport Maintenance PART 5/Heads, Guides, and Pressure Pads (Apr. 1970)

Choosing a Tape Recorder (Apr. 1972)

= = = =