by EDWARD TATNALL CANBY

SPECIAL-INTEREST LOBBY

Do we still need the live musical experience as a basis for our audio entertainment? You bet.

All kinds, but especially in lobbies.

A long while ago I conducted a con cert with my New York singers out at a university in New Jersey. When we arrived we found we had to sing in a lecture hall, one of those padded-cell affairs with low ceiling and soundproof walls. But just outside this monstrosity (for music) was a large entrance foyer or lobby, all stone and concrete, ex tending up through several floors with intertwined stairways. Instantly I knew it was a natural place for music, intended or no. It would be glorious, like St. Mark's Cathedral. So in desperation I asked if we could remove our concert to that space.

What? A concert in the lobby? That's no proper place for a cultural event! We were refused, and we sang in the padded cell. Dreadful concert.

This year, at last, I have been vindicated, if indirectly. I am back from my annual live-music Jacuzzi in Oregon, a whirlpool of glorious sound in which I bathe, three concerts a day for several weeks, and never fail to find further clues to understanding our own ever changing audio entertainment. This year in Eugene we had real lobby concerts--a whole series.

This year's special lobby concerts were entirely outside Silva Hall, the electronic concert space about which I wrote at length in 1983 (see Audio, October, November and December 1983). They were in the foyer of the same building, a place which, as far as I know, was never intended to be more than a visually magnificent entranceway. But a while back some body with a better musical ear than the architects got the idea of putting music into that big space, just as I had, back in New Jersey. The results were so good that for 1986 a whole series of free public concerts was set up, every other weekday at noon-just to now the Eugene people what this remark able place can do, even outside its concert hall. Plenty of variety: Two jazz concerts, Romantic chamber music with piano, a loud brass quintet, a batch of Baroque sonatas with harpsichord. At the biggest concert the surprised management made an on-the spot attendance count-some 862 sat and stood in that big space. Guess which concert? No, not the jazz or the brass. The Baroque sonatas with harpsichord. In the right situation, anything goes. Don't dare think that this is any less true for audio entertainment.

Silva Hall remains today a state-of the-art example of electronically assisted architectural acoustics, planned from the start to combine natural and electronic reverberation into one sound, indivisible, yet variable via computer control. Very controversial, of course-especially in the music world, where any kind of loudspeaker sound brings thoughts of canned music a la James Petrillo.

To recapitulate, there are three electronic systems in this hall. Two are for hall acoustics (that is, reverb) and the third, a standard type, is for normal stage sound reinforcement, all kinds.

One reverb system, Assisted Resonance (AR), is interconnected with another one that is quite different, Electronic Reflected Energy System (ERES). Both of them are highly sophisticated and complex but low in level, affecting only the reverberant characteristics of the hall and not conspicuously audible to the audience. These two systems were assembled in Silva Hall by acoustic designer Christopher Jaffe of Norwalk, Connecticut and his associates. Jaffe himself designed ERES, as well as the installation's inter connecting computer controls; AR comes out of England (it was first de signed for the Royal Festival Hall), from the Acoustical and Investigation Research Organisation.

AR is tailored to fit each hall, in stalled on the spot and tuned to working order with the aid of British technicians. Then the whole shebang is left to the local operators, just as the building architect and contractors leave the physical hall itself. AR comprises an astonishing overhead array of some 90 loudspeakers in a band across the curved Silva ceiling, fed individually by another overhead band of 90 micro phones, each one sharply tuned in a Helmholtz resonator to a very narrow band of frequencies.

The system uses carefully controlled feedback loops, band by band to regulate the "die-away" time at each speaker, and en masse to regulate the overall sound as the combined reverb fades away. It is really breathtaking.

ERES is a very different system based on selective delay lines out of a single mike, usually hung at the top of the proscenium arch. It feeds other strategically placed loudspeakers to provide, first, the essential 20-mS delay that we now know is necessary for a sense of stage presence in music, and second, a variable set of electronically simulated "walls" to define the shape and size of the audible space wherever one may sit.

Absolutely none of this apparatus is visible to the audience, thanks to a "false" or hung ceiling (its parameters, of course, very carefully calculated for acoustic effect) and a tall, black pro scenium arch that is actually made of a sound-transparent scrim behind which are more speakers and other nonstructural items in profusion. A triumph of artifice, yet it looks solid and real visually a pleasure (except when someone accidentally leaves a light on behind the scrim, showing all, as happened this year). This trumped-up architecture (with the "real" structure hidden behind) is, you might say, a visible ambience to match the audible, and surely no more "fake" than a thousand modern office buildings.

The hall is deliberately informal, in contrast to many--a preposterous, up side-down, green and yellow fruit bowl in lush basket weave fronted by an enormously wide and deep stage, an invitation to sonic disaster if it were not for the electronic compensations. The cool, fresh hall colors blend at the rear into darkened, burnt-ochre hallways which open out into the astonishing lobby, full of light and air. I love the whole place.

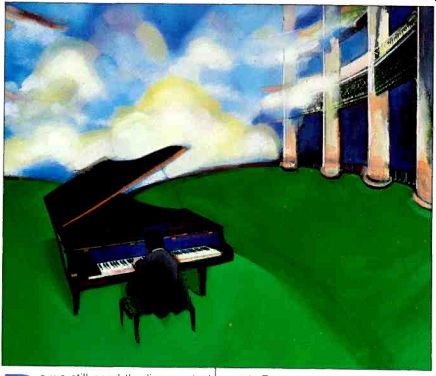

That lobby, ". . .an airy assemblage of incredibly tall, peaked roofs in wood and glass, touched up inside with lofty balconies at many levels joined by stairs paved in apple green floral car pets," I wrote in 1983, was then just a lobby. Now the space is a concert hall too, willy-nilly and by happenstance. It is huge, this lobby, a sheer architectural fantasy, thrilling to pass through as an entrance and exit to the hall itself.

But its tall wood pillars, 60 feet unbroken, the great glass expanses looking out onto sky and clouds and trees, different on every occasion and from moment to moment in sun, shade and nighttime, are too splendid for a mere lobby. Something had to happen.

And so the paradox: All that fancy audio equipment inside, all those specially calculated walls and ceilings and computer controls-and in the lobby, nothing. Nothing, that is, acoustically speaking. This leads to some faintly comic aspects when the unforeseen audience convenes. Inside the hall the ventilation and air conditioning is fault less in utter silence. But out in the lob by there is a vast rumbling of machinery, not at all soundproofed. You were just supposed to walk through, or stop and gab with friends while drinking champagne (on sale over to one side).

The lobby ventilation with an audience on hand is, alas, minimally effective. It does get a bit warm, especially in the high upper balconies, after a half hour or so. I doubt if much can be done, but no sweat; if you are warm you can always descend to a lower level, any time. There is constant movement, around and about, as the music plays.

For an architectural accident, the lobby acoustics are marvelous no matter where you sit-on the central floor, where the musicians now play in a space set off by low, moveable walls, or all the way up in the vertiginous heights of the top little balcony, hung in space as though weightless. It takes a certain amount of nerve to climb that high, so dramatic is the downward view directly above the musicians, so perilous seems the suspension. The music is reflected everywhere; the rounded side walls, the great areas of vertical glass, and the tall diagonal peaked roofs catch the sound and toss it sidewise. No matter where you go you can hear beautifully.

But you should see these concerts! They are totally informal, though no body said they had to be, simply be cause of the place itself, a glorified indoor musical picnic spot and a fine springtime advance upon our usual outdoor, blankets-on-the-grass, summer concerts. Babies crawl busily, small kids run about or do solo dances on the soundless carpeting, families sit massed on the lush green stairways, leaving a narrow space at the side for those on the move, they eat lunch (as I did), knit sweaters, hold hands, snooze luxuriously or watch the clouds go by outside. Mothers run out to retrieve infants on the loose, kids edge closer and closer to the musicians to see how they work, college students in shorts climb the heights or sit lotus-like or carry tennis rackets, backpacks, what ever. It's Americana, an entertainment style that is peculiarly ours. No wonder it was a success.

I should add that this was no noisy talk fest with background music. Far from it. The audiences were respectful and remarkably quiet. Nobody talked.

Squalling babies were quickly re moved or perhaps stopped with a cork. There was heartfelt applause often in the wrong places, but who cared? Not the musicians! Enjoy, enjoy. If you are in Eugene, visit that lob by even if there isn't a concert.

Meanwhile, what of Silva Hall itself, the main and intended place for music performance? This was the fourth Bach Festival since its opening, along with other year-round events held there, from musicals and rock concerts to solo recitals. Here I found another paradox, but maybe also a good one. My first reaction this year was one of dismay. In several weeks of concerts I heard not a single mention of the controversial audio enhancement of Silva's acoustics. For all one could tell, the whole thing might have been ripped out and put away. By now, this was merely a concert hall. Period.

I asked some of the newer musicians--they knew nothing about it; they had not been told. The college students didn't know. The more permanent residents of Eugene who once knew all about the audio (and mostly condemned it out of hand) have care fully forgotten. The music critics do not mention It. The entire electronic system has simply been shoved under a mental rug. As you car suppose, I found myself somewhat frustrated.

But look! Isn't this precisely as it should be? The concert hall, you see, is now treated as a whole and, I would say, by increasing numbers of people.

Many enthuse, some don't, but to all the present audiences this is "just a concert hall," not an experiment in electronics. The system works! It is a great success. Nobody thinks for a second about those many micro phones and loudspeakers, nor should they. What we have is a working and versatile music space-exactly as in tended.

The one big surprise is out in that front lobby.

= = = =

Also see: