MANUFACTURER'S SPECIFICATIONS:

Frequency Response: 30 Hz to 16 kHz.

Harmonic Distortion: 1.2 percent.

S/N Ratio: 56 dB, 62 dB with ANRS.

Crosstalk: -65 dB.

Input Sensitivity: Mike, 0.2 mV; Line, 80 mV.

Output Level: Line, 500 mV; Headphone, 0.5 mW @ 8 ohms.

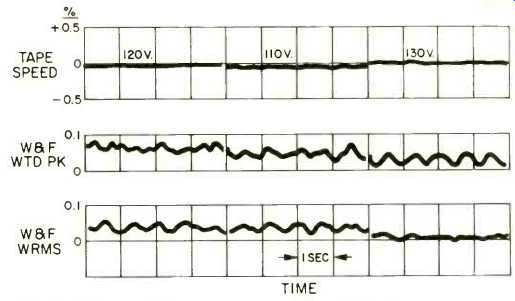

Flutter: 0.05 W rms, 0.18 percent weighted peak.

Wind Times: 85 seconds for C-60.

Dimensions: 17 1/4 in. (45 cm) W x 6 1/4 in. (15.9 cm) H x 12 1/8 in. (32.7 cm) D

Weight: 21.8 lbs. (9.9 kg).

Price: $499.95.

The JVC KD-85 is an attractive unit which has performance and user features in addition to a pretty face. The level meters get immediate attention because they have non-typical, facing vertical scales. This arrangement is faster and more convenient for matching channel levels. To the right is the Spectro-Peak Level Indicator which shows the peak levels in five separate bands, centered at 100, 300, 1k 3k, and 10 kHz, respectively. Each band has five vertical-bar LEDs with thresholds at -10, -5, 0, +3, and +6 VU. The scheme has much to offer the recordist, helping to ensure the highest possible recording level with acceptable distortion. The dual-concentric, input-level pots have large, knurled knobs with friction clutching for separate or tracking adjustment as desired. The single output level pot has a much smaller knob, slightly touchy for setting accurate levels, albeit smooth in rotation.

Spring-loaded lever switches select mike or line input, ANRS mode, 70- or 120-microsecond EQ, and bias. ANRS mode can be set for Off, ANRS, or Super ANRS. Regular ANRS, as most readers will know, is a Dolby-like noise reduction system and is compatible with Dolby B-type N/R. Super ANRS is not compatible with any other noise reduction system. For lower record levels, its action is the same as with regular ANRS; at higher record levels, however, SUPER ANRS introduces con trolled reduction in the levels of the highest frequencies. On playback, a reverse boost is given to gain a flatter in/out than if normal tape saturation had occurred. Certainly a good idea, the tests reported below show that it works quite well.

The bias switch has positions labeled 100 percent, 110 percent, and 150 percent for LN, FeCr, and CrO2 tapes, and the EQ switch has an "extra" 70-microsecond position, so the two switches will always line up. A five-position REC EQ switch provides a very useful aid to matching various tape types with equal steps over a range of about-3 to +3 dB at 10 kHz. The two-motor tape-motion drive is logic controlled and solenoid operated. Operations can be made in any order, and there are helpful status lights. Record will function as a preset, and flying-start recording is possible. Any tape motion locks out the eject button, which otherwise starts the smooth opening of the door. Head accessibility was quite good with the door cover removed, which required the loosening of two non-captive screws. The deck also has a counter with memory and a timer-start switch.

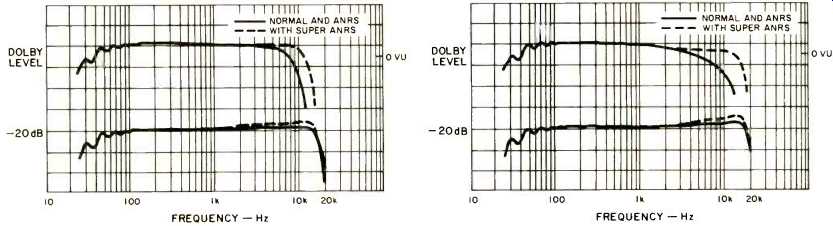

Fig. 1--Frequency response with Maxell UD tape.

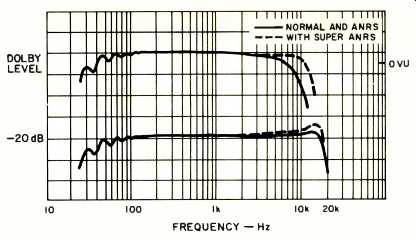

Fig. 2--Frequency response with Sony FeCr tape.

There are phone jacks on the front panel for mikes and headphones. The line in/out phono jacks and a DIN socket are on the back panel. The internal construction was of high quality with excellent soldering on the PCBs and the chassis frame was quite rigid. Adjustments were well marked, and parts were identified on both sides of the boards in many cases. This nicety is unusual, and it is a definite aid if troubleshooting is needed. Inter-card connections utilized wire wrap and most runs were bundled neatly. Other items of interest: The good-sized flywheel in the capstan drive and the mounting of power resistors on standoffs.

Measured Performance

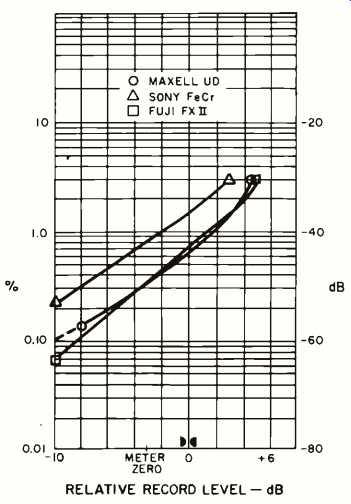

The playback responses with alignment tapes were generally within a dB or so with the exception of a droop of just over 3 dB at 40 Hz and lower. Meter indications were within 1/2 dB for the standard levels. Playback tape speed was about 0.7 percent fast. The 1-octave RTA showed that it was possible to match a large number of quality tapes with the aid of the five-step record EQ switch. The record-playback responses were excellent, in general, with superior flatness from less than 100 Hz to over 10 kHz. In all cases, the differences between normal and ANRS responses were insignificant, much better than what happens with too many decks with Dolby being switched in. All responses had a lower limit of 40 Hz, not to spec, but only slightly limiting for most music. Maxell UD had a high-end response to 17.0 (ANRS) or 18.0 kHz (normal and Super ANRS). At Dolby (or ANRS) level, switching to Super ANRS increased the high frequency limit from 8.0 to 12.6 kHz, a significant improvement. The change with Sony FeCr bordered on the dramatic, for the-3 dB point shifted out from 6.0 to 15.0 kHz. Benefits were apparent as well with Fuji FXII tape where the Dolby-level response extended from 7.6 to 12.1 kHz, although the +3 dB peak at 15.5 kHz at the lower record level is on the edge of being too much. The phase jitter in the playback of a recorded 10-kHz tone was 30 degrees, very good for a cassette deck.

Bias in the output during recording was quite low, which can help to prevent bias-beat tones if you're recording with another machine from the same line.

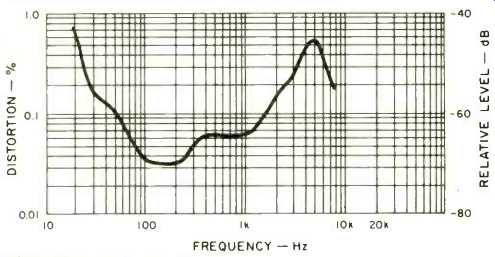

HDL3 (third harmonic distortion) was determined from 10 dB below Dolby (or ANRS) level to the 3 percent distortion point with a 1-kHz test signal. Results were as expected for the Sony FeCr and the Maxell UD, but the figures for Fuji FXII were notably lower than for CrO2 type tapes with most recorders. HDL2 was relatively high at the lowest record levels with Sony FeCr, but HDLS was very low with all formulations.

HDL3 vs. frequency was measured with the Fuji tape and was quite low over the majority of the band, especially between 50 Hz and 2 kHz. The use of ANRS or Super ANRS did not introduce any increase in distortion products, except of a very minor nature in a couple cases. The signal-to-noise ratios at ANRS levels were 51.4, 55.5, and 55.3 dBa for Maxell UD, Sony FeCr, and Fuji FXII, respectively. For levels where HDL3 = 3 percent, the figures were 55.7, 58.5, and 59.9 dBA.

With ANRS the latter values were increased to 63.8, 65.7, and 66.8 dBA for the Maxell, Sony, and Fuji tapes. Super ANRS increased these excellent figures a bit more, to 64.9, 66.5 and 67.7 dBA for the same order. Erasure was almost 90 dB, and crosstalk was more than 80 dB down, excellent performance.

Separation from one track to the other was 47 dB, much better than most decks.

Fig. 3--Frequency response with Fuji FXII tape.

Fig. 4--Third harmonic distortion vs. level at 1 kHz with Maxell UD, Sony

FeCr, and Fuji FXII tapes.

Fig. 5--Third harmonic distortion vs. frequency at 10 dB below ANRS level

with Fuji FXII tape.

Fig. 6--Wow & flutter and tape speed variations.

Mike input sensitivity was 0.18 mV, and input overload was reached at 68 mV. Line sensitivity was 74 mV with input over load somewhere above 11 V, the maximum output of the test generator. Output clipping appeared at a level equivalent to +16.6 meter indication. The input level pots tracked within a dB from maximum to 60 dB down, very good indeed. Line output was 470 mV, a little lower than the specified 500 mV.

The sections of the output pot tracked within a dB from maximum to greater than 50 dB down. Meter indications were substantially to VU meter standards for both frequency response and ballistics. Scale calibration was very close with a maximum of 0.5 dB error over most of the range. The illumination was on the low side, but compatible with the bar LEDs in the Spectro-Peak level indicator.

Tests with continuous wave (CW) tones showed that the thresholds in each of the Spectro-Peak indicator's five bands (center frequencies = 100, 300, 1k, 3k, and 10 kHz) were within 2 dB of stated thresholds (-10,-5, 0, +3, and +6) with in each band and compared to each other. This is certainly very good performance, demonstrative of excellent design and careful adjustment. With a tone in a center channel, responses were down about 4 dB in adjacent channels and about 11 dB down two bands away. Filtering is obviously not really intended to be sharp enough for any form of critical analysis by bands, but the filter shape is adequate for the purpose. With a pink-noise source, thresholds were within a 2-dB spread, the same as with the CW tone. Each band indicated a response with a burst of 25 mS or so, with the CW level set just above threshold. The bar LEDs were a bit faint, and use of this great mini-RTA was aided with relatively low room light.

During playback, the line voltage was varied from the nor mal test setting of 120 V down to 100 V and up to 130 V. Tape speed changes relative to that at 120 V had a total spread of about 0.1 percent. Flutter performance was excellent, typically less than 0.04 percent W rms and less than 0.06 percent weighted peak. Wind times were 70 seconds, reasonably fast, as well as being quiet and smooth. Logic response time was very short, without any excessive stresses being observed.

Listening and Use Tests

No matter what was tried, tape motion control was fast, smooth, and without any form of malfunction. The combinations possible with this deck are among the best available.

Flying-start recording is one, and having Pause turn on the Play status light is another. Cassette loading and unloading was convenient and gentle. Keeping the heads clean with the door plate removed was easy, but I wish the screws were captive. Pot rotation was very smooth, and the lever switches had a nice snap action going into position. Metering with the combination provided with the JVC deck was fast and convenient, and it gave the user the sense of being in control of recording levels, more so than with VU meters and one or two LEDs for peaks. The adjustable record EQ was of definite value with some of the tapes used. Memory and timer start worked reliably whenever used.

The instruction book is trilingual, and there is considerable detail in the instructions with some technical background included. The text is well illustrated with figures for interconnections and control settings. Recommendations are given for setting the tape select and REC EQ switches. There are helpful discussions on the effects of ANRS and Super ANRS and what happens if the selector switch is in a different position in playback. The section on the Spectro-Peak indicator gives explicit instructions on the level limits for each of the bands with various tapes and ANRS settings.

The JVC KD-85 delivered most satisfying results while being interesting and pleasurable to use. In general, the deck sounded just fine with any of the tapes. With record levels pushed up, however, there was an improvement in the sound with use of Super ANRS. There were no changes in sound, except for lower noise, when switching from normal to ANRS. Pauses during recording were undetectable. Record starts caused a "thump" about 5 dB out of tape noise. Record stops were more of a click and at a slightly higher level. The JVC KD-85 cassette deck has very little to fault it and a lot of convenience and performance for a good price.

-Howard A. Roberson

(Source: Audio magazine, Nov. 1978)

Also see: Link |

JVC KD-A7 Cassette Deck (May 1981)

JVC S-300 FM Stereo/AM Receiver (Sept. 1976)

Intraclean S-711 Head Cleaner and C-911A Cassette Cleaner (Dec. 1985)

= = = =